1936 - Celebration of the Franco-English

friendship in Chamonix during EDWARD VIII visit to France

speech made by PAUL PAYOT at the

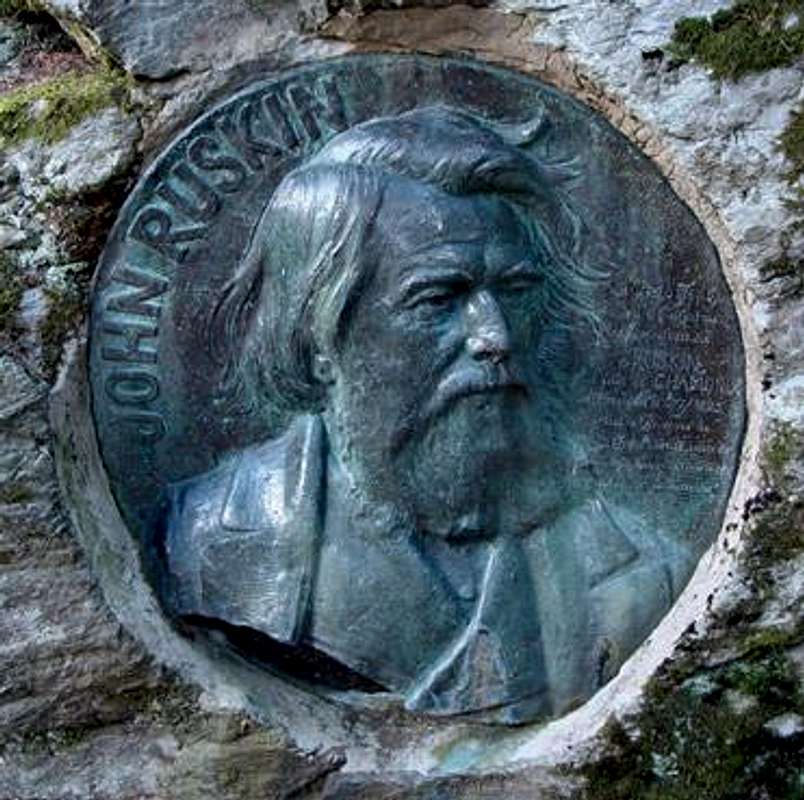

“Pierre à Ruskin”.

Some background of the Payot family and their relationship with the British by Jean Fabre

The Payot marked the Chamonix history at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries with notable characters, bankers, philosophers, doctors and of course mountain guides such as a Michel Payot (1840-1922) who did a number of first ascents particularly with John Cowell, Edward Buxton, Anthony Reilly, John Tyndall, Alfred Wills, Edward Whymper and James Eccles. Later three brothers of another branch of the Payot family created closed links with Great Britain:

Paul Payot (born in 1856), founded the Payot bank, starting his activities with changing British tourists’ pounds sterling to francs.

Jules Payot (1859-1940) the “commissioner of education Payot” (Education de la volonté, morale laïque et solidarité), writer and philosopher, played a considerable role in the French Third Republic

educational system becoming the “intellectual guide of elementary school teachers” to the point that Lenin, then called Vladimir Ilitch Oulianov living in Geneva, visited him in Chamonix a few years before his journey to Russia.

During their night long conversation, the future Lenin told Jules that the revolution would occur not in Germany as expected but in Russia. Jules swiftly took his advice: the next day he asked his brother Paul, the banker, to sell

all his Russian bonds and with that money built the current family home on the outskirt of Chamonix. Jules was a friend of John Ruskin: his family still has his correspondence with the philosopher who compared mountains to “the cathedrals of the earth”. Jules did inaugurate the “Pierre à Ruskin”, tribute from Chamonix to this admirer of Mont-Blanc and the Chamonix valley.

Michel Payot (1863-1908), the doctor, introduced skiing to Chamonix in 1902 (the first to ski the Chamonix-Zermatt route in 1903) and with his second wife, a British citizen, he made the traverse of the Three Mont-Blanc, a feminine first

ascent, neglected by mountain historians up to now.

Jean Fabre - Jules Payot’s great-grandson - (Presented and translated by Eric Vola).

Jean Fabre, a very old friend of mine, is a guide and a French prefect. His last job as such was Prefect of Guadeloupe until he damaged his back badly in a climbing accident on the island. Trained as a lawyer, he is also the husband of Lisa Afanassieff, sister of the great French climber and movie maker Jean Afanassieff ("Afa") who passed away in early January. Among a number of climbs he did with "Afa" (and a party made of Afa's brother, Michel, Giles Sourrice and Guy Abert) was the first ascent of Fitz-Roy North face in 1979. (Filmed by AFA). A great story teller, I will try and persuade him to publish later some of the best short stories he wrote up to now for his friends.

PAYOT's SPEECH

In 1936, to celebrate the visit of Edward VIII to France, Paul wrote the present speech given in Chamonix at the “Pierre à Ruskin”.

Trying in twenty minutes to recount the full history of English influence on the Chamonix valley may seem bold. I therefore limit this short review to the main poets, writers, artists or alpinists who visited our region since 1741.

On the 17th of June 1741, a party of Englishmen met in Geneva and discussed Mont-Blanc, visible far away in the evening’s mist. They were: William Windham, Lord Hadington, George Bailllie, Benjamin Stillingfleet, Chetwund, Aldworth and

Robert Price. Lastly, Richard Pocock, a famous British explorer returning from the Levant, joined them. No travel report nor information did exist about the “Cursed Mountains”. Nothing more was needed to push Pocock to organise an expedition.

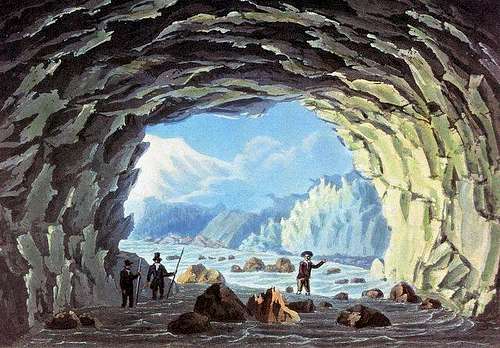

On the 19th of June, the caravan of eight masters and five servants, all well-armed, got under way. They spent the night in Bonneville; the following in Servoz and the 21th in Chamonix on the banks of the Arve. Sentries stayed on watch all night, and in the morning, the travellers were amazed to see the prior coming to offer his hospitality. Windham and Pocock do not satisfy themselves with Chamonix, they want to go onto the glaciers, despite widespread scepticism from the locals a climb to the Montenvers is organised. After a half hour stay near what Pocock baptises the “Mer de Glace”, the British departed fully satisfied with their travel results.

The duke of La Rochefoucault d’Enville speaking of Richard Pocock will later report:

“To achieve successfully this adventure, one must have been British or a knight errant; he was British. It was far worse than fighting giants… One had to walk in dreadful countries, through paths full of stones crumbling from

mountains, cross fords, defy voracious insects, of which the Savoy pot houses are filled with, his courage made him overcome all those obstacles.”

Windham and Pocock had the virtue of “opening the way”. They were the pioneers of our beautiful Chamonix valley, and perhaps even the initiators of the superb sport which we call alpinism. If one can criticise them not to have seen the Mont-Blanc (as they did not say a word about it), they enabled others to discover it. They had the merit to give a large publicity to their journey, which as an immediate consequence, attracted many visitors to Chamonix.

If you go to Montenvers, you will be able to see, on the edge of the Mer de Glace, a big granite boulder on which are engraved the names “Windham” and “Pocock” and the date “1741”. It is the “Pierre des Anglais”, tribute to those who launched the Chamonix valley.

I apologize to have spoken so long of those forerunners, but it was necessary to underline the importance of the expedition of this British party. They opened the way and if the following travellers were from Geneva, such as de Saussure, from

France, and soon all the famous British painters and writers would come to Chamonix to be enthused by our valley. The British came to the Alps very early. Already, way before Windham and Pocock, John Evelyn, in 1646, had crossed the Simplon, John Addison walked along Geneva Lake, Thomas Gray crossed the Mont-Cenis. The alpine nature however did not enthuse them, and as far as the Chamonix valley was concerned, it was ignored. Windham and Pocock’s journey pushed a number of English to visit our valley; Thomas Blaikie, William Coxe, the duke of Hamilton and John Moore, his private tutor, but their description have nothing noteworthy.

The British painters precede the writers and poets to the Chamonix valley. However with the writer William Beckford in 1780, was Robert Cozens, the famous painter who painted the wild site of the Col des Montets. Already, ten years earlier,

William Pars had sketched the first views of Chamonix and the Mer de Glace, and in 1777, the British, Schmidt, the view of the valley’s entrance.

It is only in 1790, with William Woodworth that poetry first appeared at the foot of Mont-Blanc, and it occurred in a way which was never outmatched. The discovery of the Alps was not for him a temporary flash of inspiration and a

fleeting influence, but his juvenile enthusiasm, as he was only twenty years old, transformed this first contact in a cult which he will keep all his life. With him, British poetry reaches, in its description of mountains, its most

sublime point. All his poems are lyrical, as this one:

Several years later, in 1802, Coleridge writes his famous “Hymn before sunrise in the Vale of Chamouni”:

“Thou first and chief, sole sovereign of the Vale!

O struggling with the darkness all the night,

And visited all night by troops of stars…

And you, ye five wild torrents fiercely glad...

Ye Ice-falls...

Motionless torrents! silent cataracts!

Who made your glorious as the Gates of Heaven…

God! let the torrents, like a shout of nations,

Answer! and let the ice-plains echo, God!”

What is most strange is that Coleridge never came to Chamonix, but his poem results from his friendship with Woodworth.

On the other hand, Shelley came to find his impressions at the source, and in 1826, during his four months stay in Geneva, he visited the valley. On the site, sitting on the old bridge of les Bois, at the centre of the village, he composed in exquisite and untranslatable verses his “Ode to Mont-Blanc”.

Shelley liked our mountains and glorified them in his verses. In his letters he gives us many details about his travel. Starting from Geneva, he visited the source of the Arveyron, then with Ducret, his guide, “the only bearable person whom I have known in this country”, he went to the Bossons glacier. The following day, after a short visit to the Mer de Glace which he found “truly of a breath-taking splendour”, he returned to Switzerland.

Mary Goodwin, who will become Mary Shelley, his second wife, accompanied him to Chamonix. She wrote many novels, the framework of which is inspired by the poet’ descriptions. The most known of all, “Frankenstein”, is a dark drama in which the hero takes refuge in the chaotic loneliness of the Arveyron’s source. The Chamonix valley made a deep impression on Shelley. He writes:

“The Valley of the Arve (strictly speaking it extends to that of Chamouni) gradually increases in magnificence and beauty, until, at a place called Servoz, where Mont Blanc and its connected mountains limit one side of the valley, it exceeds and renders insignificant all that I had before seen, or imagined. It is not alone that these mountains are immense in size, that their forests are of so immeasurable an extent; there is grandeur in the very shapes and colours which could not fail to impress, even on a smaller scale.”

This letter was sent to his friend Lord Byron, staying in Switzerland who immediately decided to travel on foot to Mont-Blanc. And several days later, the famous British poet and playwright arrived in Chamonix. On the 24th of July 1816, he crossed the Bossons’s glacier, not at the bottom, but at the altitude of the current hut, which at the time was quite a feat. He then visited the Arveyron’s cave and having seen enough of the valley’s curiosities he went back to Geneva. Lord Byron did not immediately appreciated our mountains. It is only later, after a journey in the Oberland and to the Jungfrau which provided him with points of comparison that he appreciated the Mont-Blanc’s beauty. His first vision of our Alps was too impressive for him and he feared, maybe, not to be able to describe them as well as hisfriend Shelley.

During those twenty years in the nineteenth century floats the genius of one of the greatest British painters, Joseph William Turner. As soon as 1801, he came to the Chamonix valley and brought back three paintings which can be seen at the Royal Academy. They are views of Bonneville, the Arveyron’s source and the Saint-Michel castle. Several years later, he will engrave a view of the Mer de Glace and one of the Arveyron. From all his sketches, a new design of landscape emerges. The Alps, seen by a great romantic and a great artist. The most beautiful works of Turner are those in which he painted mountain scenery and his magnificent understanding of the Alps will have a great influence on the person whom we are so near here, John Ruskin.

John Ruskin, born in 1819 in London comes to Chamonix for the first time in 1833, at 14 years old. He wanted to check the marvels of de Saussure and Turner’s paintings, this travel was an enchantment. Studying at Oxford, he could not return to the Alps before 1842 with his mother. He went to the col de Balme and to the Mer de Glace. At last, in 1844, he came back on his own and was lucky enough to have for companion, Joseph Couttet, former head guide. It was, then, a series of walks and treks which will give him a great knowledge of the range. All the work of Ruskin will soon be a hymn to the glory of the mountain.

“Why”, was he asking, has the sky “created the Alps, given legs to the chamois and blue to gentians and to no-one a heart to like them?” However, as far as he was concerned he had this heart not just to like them but to adore them.

Through their accuracy, all his descriptions show a deep love for the Chamonix valley. Facing us, you see the Aiguille de Blaitière… Ruskin described it in “Modern Painters” as follows:

“The white shell-like mass beneath it is a small glacier, which in its beautifully curved outline appears to sympathise with the sweep of the rocks beneath, rising and breaking like a wave at the feet of the remarkable horn or spur which supports it on the right. The base of the Aiguille itself, is, as it were, washed by this glacier… The pyramidal form of the aiguille, as seen from this point, is, however, entirely deceptive; the square rock which forms its apparent summit is not the real top, but much in advance of it, and the slope on its right against the sky is a perspective line; while on the other hand, the precipice in light, above the three small horns at the narrowest part of the glacier is considerably steeper than it appears to be…"

I apologize to quote at such length, but having the mountains in front of our eyes, we can see with how much accuracy and understanding John Ruskin describes them. He sees them with a mystic spirit: “The Mountains are our Earth’s Cathedrals”. Even if he had often wanted to justify this love with long geologic theories or new and original concepts as those of mountains, “bones of the earth”, Ruskin wrote from deep in his heart. Ruskin will come more and more often to Chamonix and the long days spent here, near this stone, cannot be counted. However he wanted to achieve more and he decided to buy land. He chose it opposite the pastures of the Rocher which we see from here. But back in 1864, after a quarrel with his seller, he broke the deal and resold the land. There only remains from this transaction the name given to this little green spot in the fir tree woods, the “Plan Ruskin”. This quarrel embittered him a little and for several years he will not come back to Chamonix. But in 1881, on the eve of the madness in which his genius will disappear, he came back again, and declared on hisreturn: “The only days which I can remember as having been spent correctly andwisely in full, had been when sighting Mont-Blanc, Monte Rosa and Jungfrau.” Despite his enthusiasm, Ruskin came too late. The Alps are not anymore deserted sanctuaries that his mysticism claims and soon it will personify the fight of the romantic spirit against a more active and realistic conception of mountains. For a long time this conception had emerged.

The British were the promoters of this new trend. During the fifty years following the first ascent of Mont-Blanc, in 1786, by doctor Packard and Jacques Balmat, amongst the nineteen ascents, eleven were made by Englishmen. The proportion of British alpinists increased year by year in the Chamonix valley.

A simple statistic shows the prodigious attraction exercised by Mont-Blanc on our British friends. From 1786 to 1878, out of the 781 people who reached the summit, 448 were British. Of the 36 women during thesame period who made the ascent, 23 were British. But numbers are meaningless and we must be thankful that England sent us its best alpinists.

James D. Forbes is the first to camp at the Montenvers, to cross many passes and to study all the glaciers in the range. He published a magnificent book “Travels through the Alps of Savoy”, entirely written to the glory of our Alps. His conception

of mountaineering is not yet one of an essentially alpinism based on sport, as with Whymper, Mummery or Stephen, but it is still already stripped of romanticism and turned towards action. James D. Forbes is instrumental to the vocations of Tyndall and Sir Alfred Wills. If the Alps inflame the first, they still remain for him a field of experiments in which he can verify his theories; his vocabulary is essentially technical, but sometimes he found sensitive words to describe the beauty of the high mountain landscapes. On the other end, Sir Alfred Wills sees the mountain immediately with a fresh spirit. He is the one who opened the way to true alpinism and to high mountain literature. In 1851, his first journey to the Jardin de Talèfre delighted him so much that he spent two months crossing the Alps. Then, over a few years, after his first ascent of the Wetterhorn with his friend and Chamonix guide, Auguste Balmat, he climbed Mont-Blanc several times. In 1856, he published “Wandering among the High Alps”, the first true mountain book. The same year appearedd the famous account “Where there’s a will, there’s a way”, by Hudson and Kennedy. More than anything else, this title shows the new way of British alpinism.

Soon after, Sir Leslie Stephen came to the Alps, he travelled to Switzerland and the Chamonix valley. He brought back many highly inspired articles. He will combine them in a book titled “The playground of Europe”. His description of the crossing of the col des Hirondelles or the one of a “sunset at the top of Mont-Blanc” are marvellous tributes to our mountains. His article on Mont-Blanc starts with these words: “I take it as an article of fundamental faith that globally no summit in the Alps is comparable in splendour and beauty”.

A climber was going to outshine all predecessors: Forbes, Wills or Stephen liked the mountains, but Edward Whymper dedicated all his life to them. With an audacity sometimes a bit mad, he storms up the Aiguilles. The Grandes Jorasses, the Aiguille Verte were soon conquered, which torn off tragic shouts of furore from Ruskin. Ruskin did not like alpinism as a sport and his famous foreword of “Sesame and Lilies” is an anathema against the new conquerors:

“You have made race-courses of the cathedrals of the earth… The Alps themselves, which your own poets used to love so reverently, you look upon as soaped poles in a bear garden, which you set yourselves to climb, and slide down again with “shrieks of delight.”

Edward Whymper, Leslie Stephen and D.W. Freshfield retaliated violently. Soon after, Whymper made the first ascent of the Matterhorn, climb which ended in tragedy with the death of three British and of Michel Croz, the Chamonix guide. Croz rests in Zermatt, at the foot of the mountain which struck him down, but Whymper rests in the Chamonix valley, at the foot of the Aiguilles which he conquered and loved.

It would be too long to list all the British who came to Mont-Blanc and whom we are proud to write the names down in the golden book of Chamonix. If I have voluntarily forgotten Dickens, Mathew Arnold, Tennyson and Albert Smith, a special mention must be made of the Prince of Wales journey. In 1857, led by Albert Smith, the man who became his majesty Edward VII came to Chamonix and visited the Bossons. I cannot but mention Freshfield, Mummery, Lord Conway, Arnold Lunn, G.W. Young, Coolidge, Tuckett, Bonney, Montagnier and so many others. All those rock flames, with the names of their first conquerors, the name of a pitch or the name of a route, remind us what we owe to the British.

In 1880, first ascent of the Petits Charmoz by J.A. Hutchinson, First ascent of the Grépon by Mummery in 1881, first ascents of the three Blaitière spikes by Richard Pendlebury, Richard Whitwell and Stuart Kennedy.

Aiguille du Plan: James Eccles in 1871, the Peigne by R.O. Gorman and the Dent du Requin by Mummery.

To the left, the Aiguille Verte range, the summit of which was conquered by Whymper, the Dru by C. Dent, the Droites by reverend Coolidge, the Courtes by the Cordier-Middlemoore party.

The Balfour gap, the Young route on the Grépon, the baton Wicks, the Mummery couloir, so many of our British who proved the unequalled attraction that our mountain range exerted and still exert onto the other side of the channel.

Today we celebrate the Franco-British friendship. I want to end in urging you to try to visualise the Glacier de Talèfre, up behind the Dru and the Verte. At the end, among the jagged-edged summits of the glacial cirque raise two peaks. One, the Aiguille Ravanel bears the name of a famous guide, a child from Chamonix, the other, the Aiguille Mummery, the name of the greatest British alpinist. And never does one name goes without the other: They are always linked and united under the name “Aiguilles Ravanel and Mummery”, symbolising in mid-air, the union of Great-Britain and the Chamonix valley.

PAUL PAYOT

Paul Payot (1912-1977), great nephew of Jules Payot, was mayor of Chamonix (1953-1960 and 1967-1969). A friend of Gaston Rebuffat and Armand Charlet, he was a writer (Ruskin et les Anglais à Chamonix) and a great art collector; his collection of some 15000 books, 2500 engravings, paintings, prints, posters, and original documents can be seen in Annecy (Conservatoire d’Art et d’histoire).