The Country's Finest Trailhead?

![Clements Mountain]() Clements

Clements![Reynolds at Dawn]() Reynolds

Reynolds

What compels those who are allergic to crowds to climb mountains in highly popular areas? Convenient access certainly plays a role. The fact that such mountains (think of the Maroon Bells, Mount Sneffels, and Mount Whitney, for example) stand as symbols of their areas and therefore exert strong emotional pull is surely another. But it's also because, for me at least, climbing those mountains makes me feel that I have earned some secret, some intimacy with them that most of the people congesting the trails in their vicinities never do. So it is for the signature peaks at Logan Pass in Montana's Glacier National Park.

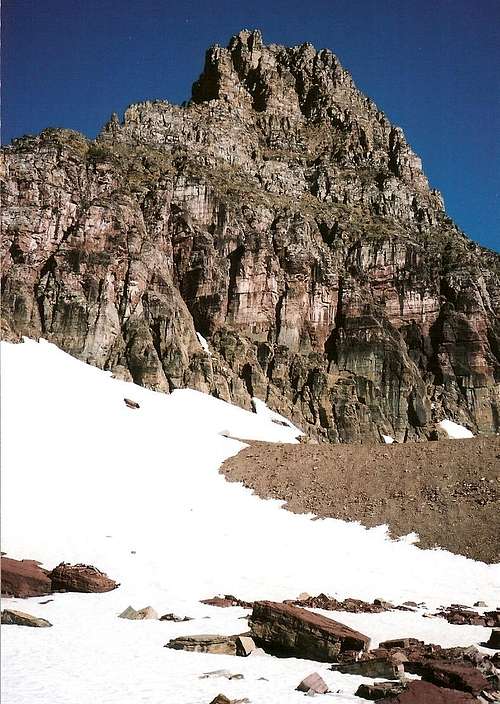

Although the views from Logan Pass are spectacular in every direction, two peaks, Clements and Reynolds, seem to have more cameras and eyes aimed at them than the other mountains visible there do. Both of them, though Clements especially, tower over the pass and make magnificent subjects for photographs, sketches, and paintings. Clements is so close that photographing without turning the camera vertically can be difficult to do without the help of a wide-angle lens.

As tired as I get of the traffic and crowds around Logan Pass, it still thrills me every time I approach and see those peaks and the setting of cliffs, waterfalls, and alpine meadows all around them. I think nowhere else in the United States reached by a paved road is as beautiful as this setting is. Even the vistas from the high 4wd roads of Colorado have a hard time competing with the scenery at Logan Pass, though anyone familiar with the Alpine Loop and Yankee Boy Basin in the San Juans or the Castle Creek Road in the Elks might beg to differ.

Now, I love hiking and climbing and exploring the wilderness, but I don't enjoy backpacking and prefer long day hikes and short, rigorous climbs instead. This is why Logan Pass is such a great climbing base. The pass gives a high, short approach to some spectacular peaks with a variety of routes and challenges. Add the fact that Clements and Reynolds straddle the Continental Divide and that I have a fascination with ascending peaks and passes on the Great Divide, and you have one of the best places in the world. Just start nice and early so that you can enjoy the area when it's actually quiet.

For a few years, I had been wanting to climb Clements and Reynolds. I chose to do Clements first simply because it is the lower peak and has the shorter climb. In retrospect, based on the routes I took up each, my decision should have been to use Reynolds as my warm-up climb. It is the easier peak both by standard routes and alternate routes.

Clements Mountain-- Tuesday, July 11

![Clements]() Clements, with the south ridge (left) visible

Clements, with the south ridge (left) visible

The route I wanted to take up Clements was the South Ridge route as described in J. Gordon Edwards’ book A Climber’s Guide to Glacier National Park. But the book, though full of precise details, lacked useful diagrams and photos, and I instead wound up pursuing my own way up except for the very beginning and end parts of the climb. I cliffed out more than once and sometimes reached overhangs or obstacles too difficult or dangerous for me to try unroped, causing me to downclimb and seek easier passage. The exposure in these areas was frequently tremendous-- the type that guarantees a long, fatal fall-- the climbing was usually Class 4 and 5, and the rock was generally decent though not wonderful-- plenty of it was loose, and anyone with plans to survive such a climb would be testing every hold carefully.

Eventually, I began to despair of ever finding a way up via this route, and I kept thinking of my wife and 21-month-old son, both still asleep in a cabin at the Rising Sun Motor Inn about ten miles away. Making my wife a widow and my son fatherless was looking increasingly possible, and it was about time to head back down and try the safer, easier-to-follow West Ridge route either later that day or the next morning.

But I hate admitting defeat, and I vowed to make one more try.

![Clements-- South and East Faces]() South Ridge of Clements

South Ridge of Clements

This time, the pitch I climbed took me to a wide, steep, and obvious couloir leading right up to the summit ridge. I'm almost certain it was the couloir I was supposed to have found lower on the mountain by following the described route. Some steep Class 3 climbing took me out into the open near the summit, and a few minutes of rock-hopping on talus and firmer rock put me up top.

The views heading up had been spectacular, and getting the full view from the top was a nice reward for my struggles and scares. Plus, I had the place all to myself. From the top, one gets a sweeping of much of Glacier Park-- from the Lake McDonald area to the west beyond the peaks of the St. Mary Valley to the east, north into the wild, glaciated country around the Canadian border, south to Gunsight Peak, Sperry Glacier, and massive Mount Jackson, whose bulk blocks views deeper into the remote, relatively lightly used reaches of southern Glacier National Park. It was also fun seeing the Hidden Lake hikers far below-- they were dark spots on the snow, and there I was high above them and away from the crowds and the noise.

![Bearhat Mountain]() Bearhat from Clements

Bearhat from ClementsI took the west ridge down, and it was easy, but I would not want to take it up the mountain. The talus slopes leading to the ridge itself are so steep and long that I can't imagine they would be anything but a thigh-burning hell. The goat trail along the north face, by the way, which gets somewhat scary reviews, is nothing to worry about if you watch where you're going. The trail is narrow and exposed, but not nearly as much as you might be led to believe. The west ridge is a pretty safe and reliable route up and down the mountain.

![Reynolds from Clements]() Reynolds from Clements

Reynolds from Clements

I ended up in a bit of a war with the mountain, but I'm glad I did what I did-- passing the challenge was both gratifying and fortifying.

Reynolds Mountain—Wednesday, July 12

![Trailside Tarn]() Going-to-the-Sun Mountain from the Hidden Lake Trail; this is just before the approach trail to Reynolds

Going-to-the-Sun Mountain from the Hidden Lake Trail; this is just before the approach trail to Reynolds![Bearhat Mountain]() Bearhat from where the real approach to Reynolds begins

Bearhat from where the real approach to Reynolds begins

To climb Reynolds, I chose the sporting North Face/East Couloir route for the ascent and the Class 2 Southwest Slopes route for the descent.

I started from Logan Pass at just a few minutes after 5 A.M. so that I could enjoy the peace and quiet and also virtually ensure there would be no climbers above me, especially in the first couloir, the one that leads from the approach route up to the start of the north face traverse. That first couloir, in my opinion, was the hardest part of the route. On the way there, bighorn sheep were my only company.

The first couloir was the hardest part because it was so steep and loose. I definitely would not want any climbers above me in there. I also wouldn't like it if there were climbers below me, either-- although I was careful about footing, I could not avoid sending some scree crashing down in a few places. You're smart to wear a helmet here even if no one's above you-- you don't know when loose rock above might tumble down or if a goat or sheep will knock some down on you.

![Clements from Reynolds North Face Traverse]() Clements from Reynolds

Clements from Reynolds

Also, stick to the left side of the couloir; the rock is sturdier there, and you can often gain elevation without giving some of it back. The climbing isn't difficult, mostly Class 2+, but it is tiring, and the couloir seems long and dark in the morning. It feels good to break out on the ledge above and feel the sun while looking back at the Logan Pass area and down to the snowy base of the North Face.

I took the northwest shoulder directly to the start of the north face traverse, but it's supposed to be easier, though a bit longer, to head right a bit and then up. The shoulder is supposed to be Class 3 and 4, but I didn't run into anything that I would call Class 4. Count on Class 3, and some of it was wet when I was there, making things a little tricky in a couple of spots.

The north face traverse is both a delight and a respite. The views are incredible and the grade is pretty gentle, making it just a really nice piece of ground to cover after climbing the exhausting couloir leading to it. Along this goat trail, there is a lot of exposure and there is a high probability you'd die if you fell, but it is usually wide enough for experienced mountaineers to feel perfectly comfortable.

![View from Reynolds]() Blackfoot and Jackson from Clements

Blackfoot and Jackson from Clements

During the traverse, there were only two spots where the trail narrowed enough so that the space between the cliffs on my right and eternity on my left made me put my hands out as I edged around the section. In good weather and snow-free conditions, this is an easy but exciting traverse, and you shouldn't let descriptions of it scare you if you like climbing and off-trail scrambling. There was one small patch of snow on the traverse, and it did block the trail, but it was small enough that I almost could have jumped over it. I didn't, and I did use my hands there.

The final part of the climb was the east couloir, described as the crux of the route and having some Class 4 climbing involved. Unless you somehow miss it or intentionally try to make the climb harder, you should find this couloir easy if you're comfortable with and adept at Class 3 pitches. I'm not sure I would call this part Class 4, either, but I have a hard time calling Class 4; it always seems to be tough Class 3 or easy Class 5 ("easy" is a relative term here).

Bad news as I exited the north face and turned the corner to walk to the east couloir: the clouds which had been hanging over the Lake McDonald area since dawn had moved in faster than I hoped and thought it would. In fact, the storm was already visiting the Mount Jackson area, not too far away. But I was too close to the top to go back on just a threat. On to the east couloir I went.

![Dragon s Tail]() The Dragon's Tail

The Dragon's Tail

The nice thing about the East Couloir is that it takes you to just a few feet from the summit. I couldn't enjoy it, though, because the storm that was approaching and which I was trying to beat hit just as I was reaching the end of the couloir. I tapped the summit cairn, took a brief look around at what was still visible, and dropped off the other side, headed for the Southwestern Talus Slopes route for my descent. Fortunately, the storm was brief and not too intense, but I did get a little early-morning hail, and by the time I got low enough to feel safe sitting out the storm, I was too low to want to go back up after things cleared out.

The SW Talus Slopes route made a fast and easy descent, but all the steep, loose talus there must be grueling to ascend. As I’ve said many times before, give me a challenging climb over safe, exhausting scree any day.

One other thing-- definitely go early. As I descended Clements at about 9:00 the morning before, I saw a helicopter-- a scenic flight, not a rescue mission-- circling Reynolds's upper reaches. It was not the only one I saw in the vicinity that morning. I was up and off Reynolds well before the scenic overflights went out to wreak their auditory havoc that day (and the bad weather probably helped, too), but I know how angry and distracted I'd have been had I been up there when one of those damned flights went by.

![Reynolds Mountain-- North Face Route]() Hidden Lake from the north face goat trail on Reynolds

Hidden Lake from the north face goat trail on ReynoldsA Few Final Thoughts

The deep wilderness of Glacier is even better than what awaits at Logan Pass, and I’ve seen a nice amount of it. After climbing Clements and Reynolds, though, I could die happily if I never made it back to Glacier again, but, paradoxically, I’ll be immeasurably sad if I never do return. Glacier is proof of God’s or Nature’s perfection-- choose for yourself-- and it occupies my memories, hopes, and dreams daily.

Comments

Post a Comment