|

|

Mountain/Rock |

|---|---|

|

|

37.83940°N / 108.0047°W |

|

|

Dolores |

|

|

Hiking, Mountaineering, Mixed, Scrambling, Skiing |

|

|

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter |

|

|

14159 ft / 4316 m |

|

|

Overview

The official list of Colorado’s Fourteener’s is a highly malleable one. Like the softer metals (gold and silver) that were excavated in the vicinity during the mining boom of the latter half of the 19th century, this list can be construed and made to fit one’s own goals as they see fit. Depending on which list or what website or whose guidebook one visits for the ‘official’ list of ranked and recognized Fourteener’s, this number will always be an ambiguous one. However, between the chief sources of information (14ers.com, Summitpost.org, CFI and the CMC); one can expect that number to fluctuate between 53 and 58. On occasion, I’ve even seen 59 (with the inclusion of North Massive). So that begs the question…since what should be treated as an empirical list, how and under what conditions are people considering unranked Fourteener’s to be included on that ‘list’?

Subjectivity is a slippery word and usually defies objectivism. And in this case, the reasons are quite subjective. If one were to boil down all the reasons that an informative source could give to include peak-A yet exclude peak-B, filter individual opinions from climbers and professionals in the field, skim off the skin (read: the outliers), so to speak, what one would have left is a narrow bell curve of colloquial preferences steeped in tradition and sentimentalism. And this is exactly why peaks like El Diente will often pop up on said lists much to the discredit of others.

El Diente shares one crucial connection with another Fourteener, North Maroon Peak. This one similarity is that both peaks occupy the lower end of their respective “Great 14er Traverses” (Mt. Wilson-El Diente, The Maroon Bells). So the tradition, well-respected and garnered advances to nostalgia to include El Diente on some lists has been around for a long time. Which, like it or not, agree or disagree, two factors about El Diente absolutely cannot be ignored: El Diente is a potentially dangerous climb and reaching its’ small summit block is without doubt one of the most satisfying climbs on any Colorado Fourteener.

At 14,159ft, El Diente has about 259’ of prominence and lies less than a mile (0.75mi.) from its proximate parent, Mt. Wilson. These last two values officially make El Diente an unranked peak. It is located in Dolores County and belongs to the Dolores Peak Quadrangle. El Diente is a steep and dangerously loose mountain. The standard route to the summit is only considered class-3 however, in my opinion, I would give it a solid 3+ or some other caveat of warning. The summit ridge is highly exposed, small and is an extremely bad place to be in inclement weather. This is the kind of mountain that climbing helmets and axes were made for (even in summer).

Taken directly from “The Colorado Mountain Club Guidebook: The Colorado 14ers- Standard Routes”, on page 200 it states regarding the history:

discovered an ascent of Mt. Wilson in August 1890 that he felt was in fact

the first ascent of El Diente.”

El Diente of all Colorado’s Fourteener’s is the western-most and consequently, the furthest from Denver (Front Range). However, since the peak only lies .75 mile west of Mt. Wilson, it’s a trifle badge of recognizance.

Mt. Wilson and the surrounding wilderness pose massive vertical relief from the thick aspen forests of the low valleys to the almost near vertical cliffs of the alpine. The Lizard Head Wilderness, especially in the autumn is a thing to behold. Because of the sheer area of the aspen coverage, the hills simply explode in every hue of yellow, orange, red and ochre imaginable. In 1932, the National Forest Service recognized the astute beauty of this area and protected it. In 1980, it received (officially) ‘wilderness status’ and has since retained that designation.

The Lizard Head Wilderness area is roughly 41,193 acres (16,670ha). Because of the frequent, heavy winters which, is typical for the San Juan’s (2011/2012 was a bit of an exception), the wildflowers come late spring into summer is astounding! Of all the wilderness area’s and mountains have to offer the climber, this small, secluded corner of Colorado has to be hands down one of the most scenic and rewarding.

There are four viable climbing routes on El Diente, all being as loose as the previous or next route and one main snow route (couloir) located on the North Face. Whether or not one feels compelled to climb El Diente, the mountain is officially named on maps and in terms of the overall experience of climbing a mountain (not necessarily a 14er mind you), El Diente is a challenging mountain that will best most of the Fourteener’s and for the novice or intermediate climber, blur the already confusing line between class-3 and class-4.

Uncompaghre National Forest

1150 Forest Street

Norwood, Colorado 81423

970.327.4261

USGS Maps: Mt. Wilson, Dolores Peak, Little Cone

USFS Maps: San Juan National Forest, Uncompaghre National Forest

Trail Illustrated: Map #141 Telluride-Silverton-Ouray-Lake City

Getting There

KILPACKER TRAILHEAD

Sitting at a respectable 10,060ft, Kilpacker is the trailhead of choice for most El Diente ventures and ascents because of its relative proximity to the mountain. Kilpacker provides access to the southern routes for El Diente and the southwestern slope for Mt. Wilson. Convenience is high for this portal.

Travel south from Lizard Head Pass on Co. 145 for roughly 5.5 miles. Turn right (west) onto FR 535 (Dunton Road). The drive from the trailhead from this point can be a bit convoluted but persist!

The dirt road will slowly climb in a northwestern direction. There will be a bit of a ‘rough intersection’ at mile 4.2. Keep driving straight through this. At 5.0 miles, turn right onto FR 207. The trailhead is only another 0.3 miles. Dunton Road is NOT plowed or maintained in winter but the frequent snowmobilers will make life easier for a short while! Parking can be tight.

WOODS LAKE

From the junction of Co 145 and Co 62, drive east for 2.7-2.8 miles on Co 145 passing through Placerville. Look for a signed road on the right side saying Fall Creek Road (57-F Road). This will be your exit. Turn south crossing the San Miguel River at 0.1 mile and set your odometer. Continue driving south and southwest for roughly 4.0 miles. At mile 4.0, turn right and continue to drive straight ignoring the side roads. Pass a small intersection at mile 6.0 and again at 7.8. At roughly 9.0 miles, there will be a forest service sign indicating Woods Lake Campground. Pull into the campground and look for the separate area used for trailhead parking (it’s quite ample).

This trailhead starts at 9,352ft and provides access to El Diente, Wilson Peak and Mt. Wilson via Navajo Lake/Basin. The trail winds around Woods Lake within a quarter-mile or so of the trailhead then zigzags across a few small streams in its first 3 miles through thick forest. The climbing initially is steep, ample roots and rocks and somewhat steady until the Woods Lake Trail meets the Elk Creek Trail in a beautiful open hillside just above tree line (make sure you have your camera!). The flies and mosquitos on this very green and tranquil approach can be horrendous in late summer but the view of El Diente as one finally crosses the saddle that descends into Navajo Basin is intoxicating!

ROCK OF AGES (Silver Pick)

From Ridgway, drive west on Co 62 towards Telluride. Crest Dallas Divide and down to the town of Placerville. Turn left at a "T" intersection onto Co 145. Drive south for 6.5 miles and then turn right onto Silver Pick Road (CR 60M). Proceed for 4.0 miles to the intersection of County Roads 60M and 59H. Turn right onto CR 59H and proceed south for 2.3 miles. Turn right at the Rock of Ages Trail sign onto FSR 645. Proceed for 2.2 miles to the Rock of Ages Trailhead.

Once one leaves the trailhead (10,383ft), The Rock of Ages Trail (#429) will start out at a moderate incline before switch-backing frequently up and out of Elk Creek Drainage.

The trail crests the ridge and drops into Silver Pick Basin high up on the far western edge ABOVE the private property. It is well at the head of Silver Pick Basin that the new spur segment connects with the old traditional route. This is the shortest approach to access Wilson Peak as it comes in at around 3.8 miles RT from the trailhead to the Rock of Ages Saddle (13,335ft).

From Telluride, drive 6 miles west on Co 145. Turn left onto the Silver Pick Road (CR 60M). Proceed for 4.0 miles to the intersection of County Roads 60M and 59H. Turn right onto CR 59H and proceed south for 2.3 miles. Turn right at the Rock of Ages Trail sign onto FSR 645. Proceed for 2.2 miles to the Rock of Ages Trailhead

Traversing to Mount Wilson from El Diente

Photo by SP member Ingman

Red Tape

is hereby recognized as an area where the Earth and community of life are untrammeled by man,

while man himself is a visitor who

does not remain.”

This was writ in 1964 and has come to stand for the importance and signifigence of keeping the wilderness wild and virgin. The wilderness act when signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson on September 3rd, 1964, legally defined what exactly constitutes a wilderness area. This act protected at its’ onset, some 9.1 million acres…Lizard Head Wilderness is but a pence in a huge coffer of coin.

There are four distinct Federal agencies that have, to varying degrees, jurisdiction over the existing wilderness areas and the new ones waiting to be established. These agencies are in order of scope: National Park Service, U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Game and the BLM.

Since the laws governing wilderness areas are typically more strict and cumbersome than National Forest or BLM Lands, the following regulations pertain to climbing, camping, hiking and simple visits specific to Lizard Head:

1.) Motorized equipment is not allowed.

2.) In 1986, regulators expanded the definition of ‘motorized’ to include mountain bikes.

3.) Hang Gliders, carts or any vehicle with wheels are not allowed.

4.) Groups can be no more than 15 people in size, 25 with livestock.

5.) It is prohibited to build a fire within 100ft. of Navajo Lake, near any source of water or above tree line.

6.) All domesticated pets must be in control whether that means via voice command or leash.

7.) It likewise, is prohibited to camp within 100ft of Navajo Lake or any water source.

And of course, as a compliment to future campers and hikers, please be considerate and remember to practice “Leave no Trace” ethics while backcountry. Use ONLY existing fire rings and never create new marks.

Other than that, all the red tape is pretty much non-existent!

There is however, the issue of access from the north via Silver Pick Basin. It's taken the TLB, CFI, CMC and Forest Service upwards of 8 years and basketfuls of hair-pulling to work out the exceedingly complicated details surrounding the land acquisition of part of Rusty Nichols' holdings to secure access since he closed off all portage from the north in 2004.

Since this is an expedient route, please do not jeopardize access for future climbers or put the current state of affairs in turmoil by trespassing across his land. This is a situation that no one wants. So please, use the new and re-routed trail (429) from the Rock of Ages Trailhead. For additional information on this resolved debacle, please visit the Wilson Peak page. Thanks!

Routes

Local Mining History

From the great Sierra’s and the plateau’s,

From the mine and from the gully, from

The hunting trail we come.

Pioneers! O Pioneers!”

--Walt Whitman

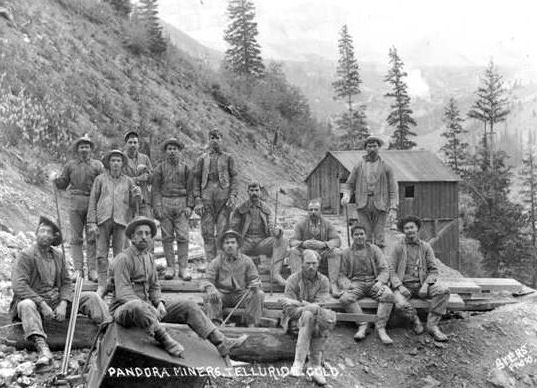

There are multiple words instantly associated with Colorado: Outdoors, skiing, John Denver, climbing, hunting, Aspen and Vail, Pikes Peak and of course, mining.

Colorado owes its expansion and pioneering envelopment to the miners and fortune-seekers that trekked into the unknown valleys and on high looking for the future. The industry of mining opened up Colorado to a far larger extent than other places than say, California, Nevada or even Alaska.

There are over 300+ ghost and mining towns sprinkled over the Rockies and another ~212 give or take, over the eastern plains. One could probably make the case that mining is a “gateway industry” of sorts in that the digging, blood, whisky and tears of failed and half-realized dreams paved the way for other industries such as ranching (cattle & sheep), general commerce, the Railroad and homesteading. Through this progression, the unknowns of Colorado became, known.

Other than the staple ores of gold and silver, other minerals were mined throughout Colorado’s history: nickel, lead, molybdenum, uranium, iron, tellurium and marble to name a few. However, it was gold and silver and that eventually uplifted some on the broken backs of others.

Many towns and cities like: Silverton, Silverplume, Silver Dale and Argentine took their name from the element that was by the late 1860’s, in short supply. Roughly ten years later around 1870, gold was starting to come into its own and in 1874, the San Juan Mountains experienced a sizeable gold rush that lasted well neigh of 30 years. Most mining towns saw their birth between 1858 and 1902. Most however, died quietly and faded back into the mountain sides like strewn Aspen leaves. The only life remaining in these lonely places is the barks of curious marmots or the occasional throttle of an ATV or Jeep. Nature is slowly taking back what was always rightfully hers.

Rising costs, weather, declining profits from supply and demand and two World Wars effectively ended Colorado’s mining era. The skeletons of these orphaned dreams and lost passions however, still remain. Of all the mountain ranges and sub-ranges in Colorado that supported mining (keep in mind, not all areas are pocked and torn from mining), the San Juan Mountains were unequivocally one of the largest.

Below is just a small sample of what lies within the vicinity of the Wilson Peak, Mt. Wilson and El Diente.

SAWPIT

A Blacksmith was the driving reason why Sawpit came into existence. The ‘smithy’, James Blake, found relatively high-grade ore in the placer and further up on the mountainside while on a scouting trip in 1895. Once a mine was dug and validated, he named him stake the “Champion Belle”. The first three loads of ore alone netted him almost $1,800 to say nothing of the following 35 loads. The floodgates opened once word got out and other would-be prospectors permeated the valley. By 1896, another major mine was opened within shooting distance of the Belle…the Commercial Mine. Saw Pit became incorporated.

I’ve read how Saw Pit was named for a nearby creek but I’ve also read how the name was derived from a rather ‘larger than usual’ saw pit on site. Saw Pits were used by the miners to basically half felled trees and lumber. One miner would hold one end of a large saw atop the pit while the other would jump down into the hole and grasp the other end and hope he didn’t get crushed. The fortune days of Saw Pit last until roughly 1905 before things started to dwindle. Now, all that’s left is some rag-tag buildings and perhaps the odd, covered foundation.

PLACERVILLE

Placerville was named for the obvious placer gold found here. Even after the gold dwindled and disappeared from the creek, the small town kept battling for life through the years, holding onto its name; fact, a small contingent of people still live here.

A prospecting party in 1876 from Del Norte led by Colonel S.H. Baker is generally credited with finding gold here. Come 1877, the rudimentary beginnings of a mining camp began to take hold. But Placerville’s start wasn’t as cut and dry as most other mining towns. If anything, the growth and movement of Placerville illustrated how flexible the miners could be gold, whisky and supplies were on the table.

Even though some cabins and various foundations were either already built or laid down, the progenitor of the saloon and general store didn’t like the original location. There was a better spot about 1.5 miles further up-valley that this gentleman liked better. So he tore what infrastructure he had down and moved his businesses up-valley. Ordinarily, this wouldn’t have been a problem since more than one individual usually built a saloon or gaming hall. However, this was Placerville’s ONLY saloon and General Store. So since going without supplies or libations simply wasn’t an option, the miners pulled up their stakes and relocated 1.5 miles further up-valley to be in the vicinity of the saloon and commerce.

Placerville grew slowly but steadily throughout the late 1800’s. Another odd twist is that Placerville’s ‘growth spurt’ didn’t come for nearly another 10-12 years and it wasn’t gold that spurned the influx but rather, ranching.

Cattlemen came first seeing the potential in the area’s fields, meadows and high plateau’s. A few years later, the real problems began…sheep herders came to town. The cattlemen hated the sheepherders. There were about 3-4 years in the early 1900’s where the violence between these two groups threatened to override the town. Fighting became a daily occurrence over the pastures. Eventually, the two learned to live with one another.

In 1904, a massive flood nearly wiped out the entire town (probably due to spring snowmelt). To give you a small comparison, this same year, 1904, F.O. Stanley and his wife (Flora) had just moved to the small town of Estes Park for the summer. The Stanley Hotel would come after another five years.

A fire nearly destroyed much of Placerville in 1919 but resiliency took over and the town was rebuilt. Due to the large parcels of private land that surround Placerville now, expansion is guaranteed to never happen. The town will never grow beyond its current borders. There are a few stragglers whom still call Placerville home and slightly more ramshackle buildings and ghosts of buildings that dot the valley.

FALL CREEK

Also referred to as Seymore and Silver Pick, during the 1890’s, Seymore was a busy mining camp located on Fall Creek. It served as the main hub for all the ore coming out of the Silver Pick Mine further up Fall Creek near Wilson Peak. It supported multiple buildings including a post office, a few saloons, general mercantile and even a small hotel. For whatever reason in 1894, the post office was actually moved TO the Silver Pick Mine. Two years later, it was relocated to the town of Saw Pit.

The officially changed its name to Fall Creek in 1922. The name, ‘Fall Creek’ is simply a general term for a river or creek that seems to have an overabundance of waterfalls.

SAN MIGUEL

Located a few miles down-valley from Telluride, San Miguel (Spanish for Saint Michael) rivaled Telluride for a short spell in terms of rowdiness, population and popularity. The town had a very decent gold and silver mine located nearby and cattle were a daily aggravation that just had to be tolerated. Telluride never really suffered this problem at least, not to the extent that the lower altitude towns did. What San Miguel did have going for it were excellent foundations. The town was laid down very smartly and conservatively. Not too many trees were cut down nor was the creek diverted. However, in the end, Telluride won out. San Miguel was a bit too much on the quieter side and placid.

OMEGA

A one-time and short lived settlement located near Placerville but its exact location is sketchy at best. The town’s odd name (for a mining camp) came from some of the settlers opinions that “this was it”.

Being the last letter in the Greek alphabet, the connotations that Omega was the last town for gold were apparent. It lasted roughly 10 years.

VANADIUM

Located up-valley from the Belle Champion Mine, Placerville and Fall Creek, Vanadium was little more than a rag-tag, rough mining camp. The town grew around a huge mill operated by the U.S. Vanadium Corporation. Like Omega, it too experienced a tragically short lifespan but buildings still exist including the old post office.

I’ve seen other town names mentioned in some of my readings like: Hangtown and Dry Diggings but I have yet to actually come across any information on these ‘towns’. This is a common theme in the mining years throughout Colorado. Towns will literally spring up overnight only to disappear after 6 months to a year, give or take. Usually the gold will play out, the claim(s) end up proving unfruitful, weather or snow will force people out or distances needed to travel to attain supplies is too great. In such instances, I’m inclined to think that these homesteaders/miners set up nothing more than small encampments.

Camping

Without making this section needlessly too long based on which approach one is going to use since Wilson Peak, Mt. Wilson and El Diente can all be day-tripped from every trailhead, I’ll explain a little about the most centered/convenient or oft-used areas for camping.Probably hands down the one area most people use to camp for these three peaks is Navajo Lake located at 11,120ft. This pristine lake located just below treeline is situated 0.3 west of El Diente and 0.45 miles west of Mt. Wilson. Wilson Peak (and the Rock of Ages saddle) is roughly 0.7 miles from Navajo Lake.

There are ample sites available to camp at around the lake with additional sites located 0.1 mile ‘up-valley’ from the lake on its’ northern fringe. Most of the sites are located across the outlet where the trail first meets Navajo Lake on its western end. Just look for and utilize existing fire rings to avoid degradation of the forest since this is a wildly popular destination in summer. A few camping sites don’t allow fires but these, the last time I was up there were signed as such. Just remember to practice ethical camping habits so future campers can equally enjoy this beautiful and sheltered basin.

Camping of course is also an option at Woods Lake Campground. Hiking and climbing these Fourteener’s in a day from Woods Lake will be a bit of a stretch but is quite doable as a long day.

The campground, located 0.4 miles from Woods Lake and 0.75 miles from Lizard Head Wilderness is situated in multiple thick stands of Aspen. It is comprised of three loops, one of which is designed for horses. This horse loop has a corral with five paddocks and a watering trough. A large parking lot is available for parking horse trailers. The campground is an excellent base camp for hikers and horses to access Lizard Head Wilderness. There are incredible views looking south from the campground of mountains in Lizard Head Wilderness. And, of course, the "quaking" leaves and majestic fall colors from the Aspen, add to the draw of this campground.

The campground is $14.00 per day with a 2 week maximum stay. This is a seasonal campground opening its gates around late May and closing mid-September. Tables and grilles are available, vault toilets and fishing is allowed (Cutthroat and Rainbow). There are four water spigots but no public phone or flush toilets. This is a first come- first serve campground.

There is also car-camping at the Kilpacker Trailhead but this is limited to the spaces available. I have yet to ever run into a problem (twice) doing this.

Mountain/Local Weather

Click for weather forecast

Miscellaneous

Fourteener Trip Reports by Tim Briese

Wild Snow (Lou Dawson)

Mt. Wilson/El Diente (E to W Traverse)