Ski-Mountaineering Split Thumb, Cairn Peak, Juneau Icefields

SKI & CLIMBING TRIP

JUNEAU ICEFIELDS

CAIRN PEAK, SPLIT THUMB,

LEMON GLACIER, & PTARMIGAN GLACIER.

February, 1978

By MtnGuide

For contextual background on Cairn Peak geography, see its SP page first, at:

Cairn Peak.

In the excitement of the first sunny and warm winter day after months of rain and snow, I bumped into a mountaineering friend on the streets of Juneau. I proposed we go ski-mountaineering on the Juneau Icefields, 3,000 feet above the fiord I lived along. He accepted on the spot.

I scooted home and called another mountaineer from Juneau. Both these men had climbed Mount Denali, so had experience in high-altitude mountain climbing for weeks on end.

We chartered a helicopter, with pontoon floats for sea and snow, from TEMSCO on Douglas Island. After work on a Friday we ran out there and loaded up, and the helo lifted vertically from the helipad a few feet above the saltwater fiord of Gastineau Channel on the Inside Passage.

The helo dropped its nose and started climbing in a slant, up over the saltwater, the marshes, and the wooded ridges, revealing sudden views out North toward Skagway and the Chilkats, upward to 5,000 over roaring creek canyons, then cliff faces and sub-peaks, to a camp of the Juneau Icefield Research Program.

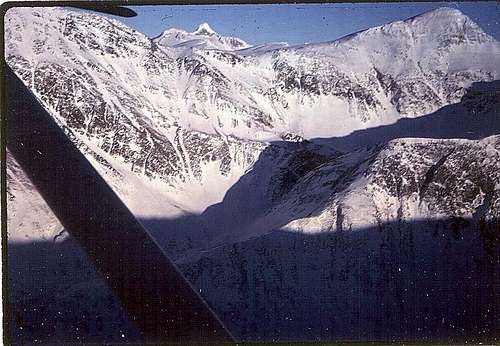

![Juneau Icefield s West Edge]() Western edge Juneau Icefields, Split Thumb center, Observation Peak right, North of Cairn.

Western edge Juneau Icefields, Split Thumb center, Observation Peak right, North of Cairn.

From those snowed-in shacks we set up tents in a bergschrund-like cleft behind a rock protecting us from the prevailing winds. A storm was brewing despite the forecast, and the clouds were blowing in and dropping.

In our excitement to be in such a dramatic place we took off from camp as quickly as possible to explore the glacier and icefield.

We skied Easterly in early evening in the gloom of an incoming storm.

We roped up to prevent falling into a crevasse. If we couldn't prevent it we could at least be more easily rescued by other belayers should we fall into a crevasse.

Our destination was Split Thumb, a nunatak spire of granite sticking up out of the icefield. It took us about half an hour to ski across to the East. We had expansive views out to the South, where several glaciers flow down the south side of the icefield into the Taku River canyon.

At last we were able to peer over the edge of the Norris Icefall. It is a glacier that is breaking up as it creeps over the edge of underlying cliffs and becomes crevassed. It was eerily blue in the dusk of the winter evening, becoming white farther down where it leveled out and restored its solidity.

This section is The Dead Branch of the Norris Glacier, and the section far below, where it re-joined the Main Branch of the Norris Glacier, was a wider valley with cliffs, extending Southerly another few miles, emptying into the Taku River.

The storm was starting to spit snow, so we had to ski back in oncoming night, into the wind, albeit toward the lingering light of the sunset shining through beneath the clouds on the Western horizon above Icy Strait out to the Gulf of Alaska.

Cooking inside the tent on our mountaineering stoves, we listened to the patter of tiny bits of ice pelting the thin skin of the rain fly, and the steady thrum of the rainfly in the increasing wind.

After dinner I went out and looked up into the breeze, and let the ice pellets sting my face. It was an exciting time of the year, full of potential for stormy adventure, new rock towers to climb, and more trips in longer daylight through the upcoming spring and summer.

NEXT DAY:

Immediately upon waking I got up out of my sleep sack to see what weather was in store for us. The day was still dark, and the snow was blue. But as the sun started to peek up over the Eastern horizon from behind the lingering cloudbank over northern British Columbia Canada the trailing edge of the system was moving over the top of us, and kept moving on East.

By breakfast we could see all the way Northwest over the top of the Inside Passage, the Chilkat Range and Glacier Bay, to Mount Fairweather, at 15,000 feet plus. From there one would be able to see Mount Saint Elias, another 100 miles North, at 18,000 feet. (See photo on Alaska Coast Range page, and Saint Elias page.)

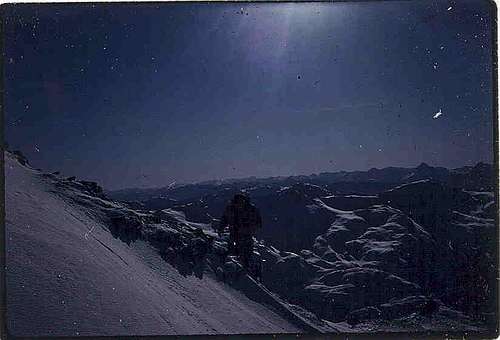

![Mendenhall Glacier Towers]() View out to Icy Strait, at mouth of Glacier Bay, to the Fairweather Range and Gulf of Alaska.

View out to Icy Strait, at mouth of Glacier Bay, to the Fairweather Range and Gulf of Alaska.

We broke camp and skiied West up over the head of the Lemon Glacier, South of Observation Peak, toward Cairn Peak.

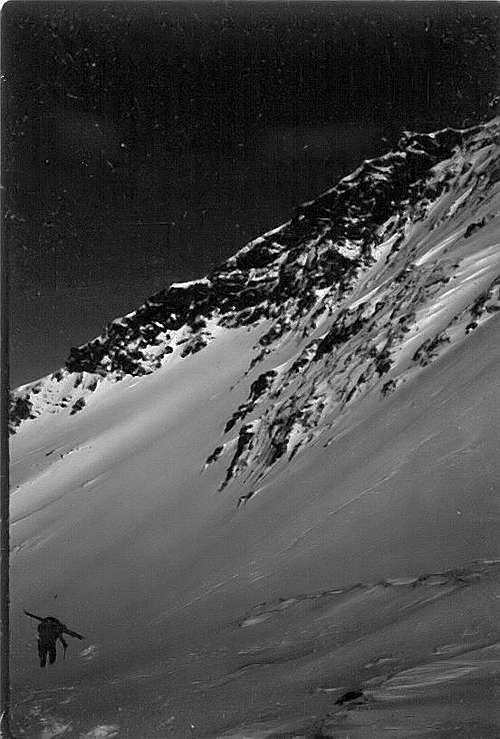

![Cairn Peak Face To Climb]() Cairn Peak from where we dropped over the edge of the rim to descend to the Ptarmigan Glacier.

Cairn Peak from where we dropped over the edge of the rim to descend to the Ptarmigan Glacier.

It turned out that there was a massive cliff in our way to reach our return route down Blackerby Ridge, into the Salmon Creek drainage. If we were to climb around the top-most shoulders of Cairn Peak we would have to side-gouge across the high face of the peak, several hundred feet above the Ptarmigan Glacier. We didn't know the footing up there and were not carrying rock climbing gear like pitons, nor ice and snow pickets.

So we re-mounted our skis on our packs, strapped on our crampons, and side-stepped out over the edge of the cliff, hundreds of feet above the Ptarmigan Glacier. We got nervous about the steep exposure if any of us were to fall, so roped up for belaying.

![Descending Lemon Glacier Ridge]() Over the edge of the cliff in crampons.

Over the edge of the cliff in crampons.

Under apparent avalanche snow conditions from fresh snow heating up in this spring sun, we downclimbed to a less steep headwall of the glacier's bowl. We had to use some side-pointing techniques, walking sideways, with the ice-axe handle point into the glacier for bracing, and sometimes kick out flatter steps as platforms for the guys behind.

Then we crossed the head of the bowl, and angled up toward the inflection point in the ridgeline where the steep section met a flatter part of the ridge.

![Climbing Cairn Peak]() The inflection point, where glacier meets ridge base.

The inflection point, where glacier meets ridge base.

We then had to climb the face of that ridge, kicking steps into the face, and eventually trying various cramponing techniques, including some front-pointing. At the top of the ridge we swung iceaxes overhand into the wall to brace and pull, but most of the way we were able to side-point, or stomp steps into the snow to step up.

![Climber Ascending Cairn Peak]() Climber Ascending Cairn Peak from Ptarmigan Glacier.

Climber Ascending Cairn Peak from Ptarmigan Glacier.

By the time we got to the top of the ridge it was 10 or 11 a.m., and the sun high on the horizon lit up the whole Coast Range to southward.

As Bob unroped himself above the avalanche zone I took a photo that showed Mount Juneau's ridge behind, Devil's Thumb 50 miles South on the Stikine Icefield, and near Petersburg, Mount Burkett or other peak 70 miles South by Wrangell, and innumerable other unnamed peaks beyond Ketchikan into northern BC near the Skeena River Canyon.

![Cairn Ridge to Stikine Icefield]() Photo 7. Unroping on the ridge crestline after the climb. Mount Juneau on next ridge, and Stikine Icefields beyond Taku Canyon, Devil's Thumb sticking up above all the rest.

Photo 7. Unroping on the ridge crestline after the climb. Mount Juneau on next ridge, and Stikine Icefields beyond Taku Canyon, Devil's Thumb sticking up above all the rest.

THE LONG SKI HIKE OUT:

By the time Scott had climbed up to join us and unrope to eat some lunch on our high ridge, we were able to reconnoiter most of our remaining route.

Down below was Salmon Creek Reservoir, and its long ridge running out to Gastineau Channel. We would have to hike and ski down Blackerby Ridge as far as we felt comfortable, then downclimb the South side into the Salmon Creek drainage.

Despite the snowfall the night before the tops of rocks were sticking up out of the ridge, and unknown rocks might be under the snow down on the South face above the reservoir.

We decided to ski along the ridge where most of the snow was, especially on the south side where wind had deposited powder drifts. It was still cold enough that the powder had not turned to sludge. We ended up with excellent corn snow that stacked up against our boots, providing enough resistance to prevent uncontrolled sliding. No ice or crust plates were encountered, nor even surging or sudden slowing.

We could ease into rhythmic down-up-down arm-swinging, even with packs on, crampons away from face, and carve some turns.

After a long sweet ski we finally ran out of sufficient snow to cover all rocks, and mounted our skis back on the tops of packs again.

![Blackerby Ridge, Cairn Peak in back.]() After skiing the ridgeline down, crampons went back on, to stomp down through the forest on snow and ice covered logs and rocks between the trees until after dark.

After skiing the ridgeline down, crampons went back on, to stomp down through the forest on snow and ice covered logs and rocks between the trees until after dark.

We decided to get off the ridge where the trees started encroaching,to avoid tree navigation problems with skis on packs, and to stay close to the open edge on the up-canyon side of the copses.

Descending the South slope of the ridge was an unexpected struggle. You couldn't just walk with lugged hiking boots we had used for snow hiking and skiing, because the rocks were covered with moss, which held water, which had turned to ice, and was covered with snow. So you couldn't tell where the rocks were anyway, and they twisted the ankle under the snow.

So we re-donned our crampons, and used them to grip the ice-covered mossy rocks and logs under the snow. Though this still caused some twisting of ankles we at least had the security of feeling the prongs bite into the underlying ice and frozen moss, and tree branches.

Surprisingly, even the waterlogged tree logs gave satisfying security when bitten into by the feet with crampon points. The water had frozen into ice. There was a certain lagging as they ground through the rotten wood, into the ice. But sometimes there was an even more certain and scary stopping, when the wood wasn't rotten, and held the crampon points too tightly - before our momentum would grind over them like tank tracks. When they didn't release we would have to stop suddenly, back up, and kick them loose.

The opposite sensation was encountered when we'd hit rocks. The ice-covered rocks, obscured by snow, would send the crampon points skittering through the thin veneer, and almost send us skittering, with sharp snaps to the joints.

Holding onto trees with gloves and mitts was a welcome security in those steeps. Ice axes were also welcome stabilizing tools, especially when one had to lean under branches with skis mounted vertically on pack, or twist into awkward positions torsionally to wind around trees with skis mounted horizontally.

DARKNESS FALLS:

By the time we had descended all the way down to Salmon Creek it was 6 pm, dark, and we still had to walk out a couple of miles. Our quads were wasted from all that weight pounding down, and our ankles were sharply pained from all the twisting in the rocks.

But as darkness came on, the stars came out, and we climbed up onto the top of the covered flume, where we could walk with confidence (we thought).

The flume cover was icy from rime refreezing, and in some places it had plate ice overflow, where the crampons suddenly would not bite so easily as they did in wood. At those moments we would skitter a bit, lose balance, and struggle with intensity to avoid falling off the flume into freefall to the creek roaring 20 feet below.

By the time we got out to Glacier Highway it was full-on dark. We could barely see. But down there in the gravel pull-out was Scott's wife, waiting with their car to haul us all home.

The silhouettes of Douglas Island, and soon of Gastineau Ridge, gave way to the lights of the city, and as I humped my skis up the steep boardwalk and stairs of my 1800s home downtown, I was glad to be living in such a close proximity to that massive icefield perched over the mountains 3,000 feet above.

I'm ready to go again. Are You?

External Links to More Photos.

Lemon Glacier, Norris Icefall, Ptarmigan Glacier, Blackerby Ridge, Salmon Creek, and Juneau aerial photos from helo, at McCullyWeb.

Comparison of glaciers' former and present extent, using photos, Google Earth and USGS maps, by Mauri Pelto and Maynard Miller, Juneau Icefield Research Program.

Temsco Helicopter Charter

Juneau Icefield - Wikipedia

Comments

Post a Comment