-

9516 Hits

9516 Hits

-

78.27% Score

78.27% Score

-

9 Votes

9 Votes

|

|

Route |

|---|---|

|

|

48.98965°N / 113.6515°W |

|

|

Hiking, Mountaineering, Scrambling |

|

|

Summer, Fall |

|

|

A long day |

|

|

Glacer NP III & IV |

|

|

Overview

All of the climbs I've done in Glacier National Park have been special for their own reasons. The good company, the interesting vantage point of peaks throughout the park, the constantly changing sedimentary rock formations, are just a few of the reasons why every peak I've visited has been unique in its own way. Still, the thought of climbing Chief Mountain was, well, different. Ever since learning the historical and cultural importance of the mountain, climbing it had felt very taboo to me; what right would an insignificant, ignorant young scrambler like myself have to grace the slopes of this sacred peak? But then I'd see Chief late in the day, often after stopping at Two Sisters near Babb to celebrate another summit venture somewhere else throughout the park, and the view of its incredible east face towering above the Great Plains only served to lessen my inhibitions about visiting its top. As a self-appointed steward to all things wonderful about the park, I spent some time contemplating the matter. After some soul searching, I decided I had to climb Cheif, and hoped that the trip would involve experiencing as much of spiritual aura of the peak as it would permit. So, with a couple of hardy companions, we planned a day long excursion up the Lee Ridge Trail to the West Slope Route of Chief Mountain. It would be a day I hope to never forget. The following route details a long, scenic, and incredibly enjoyable route up Chief Mountain's crumbled west face.Getting There

Glacier National Park is located in northwestern Montana, and shares a border with Alberta, Canada's Wateron Lakes National Park to the north. The nearest major area of the park to Chief Mountain is Many Glacier, which is accessed via a rough 12 mile stretch of road starting from the unincorporated town of Babb, MT. Accommodations along the east side of the park are abundant; St. Mary, located at the eastern terminus of the famed Going-to-the-Sun Road, offers a variety of motels, cabins, and camping areas; there is a great campground and cabins at Duck Lake Lodge; and the Many Glacier Valley offers visitors an extrememly popular campground, a historic 214 room Swiss-style lodge, and quaint guest cabins.Chief Mountain is typically accessed from various points along the Chief Mountain International Highway, a bumpy and scenic road that intersects US-89 4 miles north of Babb. The trailhead for this particular route can be a little bit tricky, but the following description should be helpful. Take US-89 north of Babb for 4 miles before turning left on the Chief Mountain International Highway/MT-17 towards Chief Mountain Customs and Waterton, Alberta. It's 13 miles from the intersection to customs. Less than a mile from the border, the road will wind uphill and to the right; keep your eyes peeled along the opposite ditch for a small orange marker staked to the side of a tree - that's the Lee Ridge Trailhead. There is no parking next to the trailhead, but you can either park at a pull off area 1/4 mile south of the trailhead or 1/2 mile further up the road near customs at the Belly River Trailhead. A few feet along the trail, a brown trail sign with distances to Gable Pass, Slide Lake, and Belly River Ranger Station lets you know this is the correct place to start.

Special Considerations

Blackfeet Use Permit

Approaches to Chief Mountain from the east, including the Humble Approach, far and away the shortest and easiest route to the summit, cross the Blackfeet Indian Reservation and require a special Blackfeet use permit. Contact the Blackfeet Fish and Wildlife offices in nearby Browning, MT if you prefer to use this route. Information can be found at their website. The approach via Lee Ridge is entirely within Glacier National Park, and although no entrance station is passed en route to the trailhead, a park permit still is required. The nearest permit stations are located at the entrances to Many Glacier and the Going-to-the-Sun Road in St. Mary. Click here for information on entrance fees.

Guidebook

J. Gordon Edwards' A Climber's Guide to Glacier National Park is a necessity for anyone who wants to safely and efficiently enjoy the countless backcountry treks and climbs within the park. It's a wonderful read, has many interesting route descriptions, and provides great historical and geological information about various points of interest throughout the park. An absolute must for any serious mountaineer in Glacier.

Route Description

Lee Ridge Trailhead to Gable Pass

First off, make sure to get an early start. It took our group of five very strong hikers about 11 hours to cover the 18 miles out and back to Chief's summit. From the Lee Ridge Trailhead, the trail winds through thick deciduous forest, gradually gaining elevation, for approximately four miles. Views are sparse at best, but occasional glimpses of the north face of Chief Mountain through the foliage add to the excitement of the hike. Eventually, the forest begins to open up, and large cairns next to the well-worn trail help guide the way.

As you leave the forest, the maintained trail dissipates slightly, but it doesn't really matter. The only thing you can get lost in at this point is the spectacular scenery. The trail opens up completely and is surrounded by the glorious grassy meadows of Lee Ridge, and affords unbelievable views in every direction. To the west, Mount Cleveland lumbers above all, with Mount Merritt's glacier-covered face glistening further to the south. The expansive forests of the Belly River drainage blanket the valley floor below in a coat of lush green, surrounded by mountain slopes and cliff bands of varying color: white, yellow, red, black, grey, and brown. To the east is the loose west slope of Chief Mountain, with the saddle connecting to the folded spires of Ninaki and Papoose peaks. Looking up Lee Ridge, a slew of sedimentary rock around Gable Pass and the sharp, pointed peak of Gable Mountain are prominently displayed. Altogether, it's less than 2 miles up Lee Ridge to Gable Pass. The trail is essentially nonexistent here, but there are an abundance of fantastic large rock cairns that help guide the way to a trail juncture at the top of the ridge. At this point the Gable Pass Trail is intersected the Gable Pass Trail from the west, which originates near the Belly River Ranger Station far downhill to the west. Follow signs towards Gable Pass and Slide Lake (southeast) and descend a short ways through a fantastic boulder and talus field to Gable Pass.

Traverse from Gable Pass

Continue over the pass, and you'll soon be heading back downhill via a series of short, steep switchbacks. After a few minutes, the trail flattens out and bends to the right. A very obvious climber's trail will eventually appear to the left; follow it off-trail through a grassy corridor bordered to the south by a rocky hill. The trail climbs uphill through the corridor, toward a large talus slope ahead and to the left. The talus slope leads up to the fabulous jagged finger of Papoose peak; at this point, you can either traverse the talus slopes, skirting the bases of jumbled Papoose and Ninaki peaks, or descend to the grassy area beneath the talus, where you'll cross meadows and seasonal drainages. Up-close views of Papoose and Ninaki are stunning, so I would recommend taking the high traverse at some point during the trip. Soon the saddle west of Chief Mountain is visible; a game trail will be encountered that will take you up and around the saddle to the base of Chief's west face.

West Slope Route

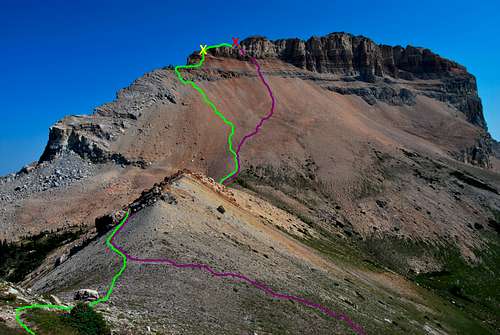

The large, loose west face route of Chief Mountain. The green line denotes ascent route up scree field, with our route angling to the solid north ridge. After a class IV move along the north ridge (yellow "X"), you'll soon reach the desired summit notch (red "X"). The purple line shows the descent route down the massive scree slopes.

Summit

To be quite honest, it was a little overwhelming to finally be on top such a special piece of rock... random mementos have been left atop the summit, including a cow skull (possibly a bison skull, like the old Blackfeet legend says, but unlikely), elk antlers, and a bundle of sage. The views to the east appear neverending (on a clear day the far off Sweetgrass Hills are most certainly visible), and the feeling of looking across the Blackfeet Nation is both exciting and bittersweet. After quietly marveling at the peak in silence for a few minutes, I surveyed the rest of the park to the south and the west. Chief provides a unique vantage point back into the park, and all of Glacier's six 10,000 foot peaks, Cleveland, Stimson, Kintla, Jackson, Siyeh, and Merritt are at least partially visible. Many of the peaks of Many Glacier can be identified to the south west, including Allen, Gould, Grinnell, and Wilbur. The massive bulk of Yellow Mountain spreads out across the Otatso Creek valley, with aptly named Slide Lake (the lake was formed in 1913 after a large rock slide dammed the creek) lying in the middle of a wide, U-shaped valley. Looking down the steep east face is particularly rewarding; an obscure devastated area dotted with colorful meltwater ponds serves as a memorable reminder of the fragile, fluid nature of Glacier's sedimentary peaks. According to Gordon Edwards, the damage occurred due to a massive event in 1972 in which a significant portion of the mountain's northeast face broke off and desolated the land 3,000 feet below. Some of the boulders at the base of the east face appeared to be as large as houses. Now wouldn't that have been an unbelievable show?!?!

Descent

To start the descent, retrace your steps down and around the west edge of the summit block, and descend through the large gap blocking easy passage to the false summit. Regain the climber's trail up and over the false summit and back down to the great notch in the mountain's north ridge. Rather than downclimb the solid north ridge, head left through the notch down a large scree gully. The rock is very loose here, so make sure to descend the gully one at a time to avoid any throwing rocks at your climbing party. A few short class III cliffs need be maneurvered, but soon the upper cliffs of the west slope are left behind. All that lies between you and the saddle below is a large, surfable scree field. From this point, you can jog down to the saddle in well under a half hour. We detoured left after traversing the saddle into the large grassy bowl well south of Ninaki peak. Wrap around Ninaki and Papoose to the southeast, a few seasonal drainages and steep grass banks. Eventually, you'll reach the talus field that leads back down to the corridor to the trail south of Gable Pass; once on the trail, it's about 7 miles back to Chief Mountain International Highway and your waiting vehicle. Altogether, it took our group of strong hikers/climbers about 11 hours to complete the 18 mile round trip trek.

Essential Gear

One more plug for J. Gordon Edwards' A Climber's Guide to Glacier National Park. Great route descriptions of peaks all throughout the park. I would also highly recommend bringing a compass and a map for the off-trail sections of the route, as well as for identifying peaks from the majestic summit of Chief Mountain.Pack plenty of water! There are no real reliable sources along the entire route, so make sure you are well stocked in advance.

Glacier National Park is home to many dangerous animals, including mountain lions, black bears, and grizzly bears. Bring bear spray, a buddy or two to hike with, a loud voice, and you should be fine.

Sturdy, dependable hiking boots, first aid kit, rain gear, warm clothes, etc. All the necessary items for strenuous off-trail mountain scrambling and hiking.

External Links

National Park Service - Glacier National Park page; information on camping, entrance fees, history, etc.Reservations for Swiftcurrent Motor Inn & Many Glacier Hotel - Glacier Park Inc.

Two Sisters near Babb

I wanted to find some excuse to use this photo on the page. Great environment for post-hiking margaritas and food. Between Babb and St. Mary on US-89.

Photo courtesy of slowbutsteady