-

92571 Hits

92571 Hits

-

94.22% Score

94.22% Score

-

47 Votes

47 Votes

|

|

Mountain/Rock |

|---|---|

|

|

44.66800°N / 7.08943°E |

|

|

Piedmont |

|

|

Mountaineering, Trad Climbing, Ice Climbing, Big Wall, Mixed |

|

|

Summer |

|

|

12601 ft / 3841 m |

|

|

Overview

Monte Viso 3841 m

Monte Viso 3841 m is a stand-alone high peak belonging to the Alpi Cozie Meridionali: all around is 500 m lower! Monviso is the contraction of Monte Viso and it's the name commonly used on the Italian side to indicate the mountain. It belongs to the Alpi Cozie Meridionali and it's the only mountain located in the Southern part of the Western Alps overcoming the 3500 m of altitude. Monviso stands out among all the mountains of Piedmont in reason of its unmistakable pyramidal shape and its grandeur, like an isolated giant among a crown of far lesser peaks. It is a wonderful and majestic mountain, with shapes to be admired from wherever it is observed.

The name Monviso probably derives from the Latin Mons Vesulus, which means "clearly visible mountain", a very pertinent name as it is visible and recognizable even from great distances. This privileged position and its visibility from the Po Valley makes it a very popular mountain for climbers and therefore often attended during the summer, also for the fact that the Via Normale that climbs from the Italian side presents low difficulties. However, it is not a climb to be underestimated as it is very long. On the route there are also sometimes snow residues even in summer which can increase the difficulty.

The mountain is very close to the French border but is entirely located in the Italian territory. Since 2016 it's part of the Monviso Natural Park on the Italian sector, while the Queyras Natural Park insists on the French side. The mountain is placed on the watershed Vallanta-Po, on the border ridge between Italy and France, very close to the French border, but entirely in Italian territory as well as almost all the rest of the group. In fact the summit is situated towards Italy with respect to the water separation line. The Monviso group is surrounded by the Po valley, Varaita valley and, from the French side, the Guil valley.

The summit of Monviso is made up of two separate peaks: Punta Nizza, the Northernmost and lower, and Punta Trieste, the Southernmost, which is the point of maximum elevation (3841 m). From a geological point of view, the mountain is made up of metamorphic rocks (prasinitic metabasalt, metagabra and fine metabasalt).

Monviso is well known also because at its feet, at Pian del Re, in the upper Po valley, there is the source of the longest river in Italy, the Po river. The source originates from the high glaciers and from the numerous lakes located on the lower slopes (Fiorenza, Grande, Superiore and Chiaretto). The waters are collected at Pian del Re, giving origin to a stream already remarkable.

It was more than 2000 years ago, Ancients thought Viso was the highest mountain in the Alps !

History

The first known ascent of Monviso was performed by the party composed by the British William Mathews and William Jacob with the guides Jean Baptiste and Michel Croz in the year 1861, August 30th. The word "known" is used as this first ascension is especially questioned by some French scientists. According to studies carried out, the summit may have been reached over a century earlier during the topographical survey of the territories of the Dauphiné organized by the French General Staff in 1751. On this occasion it seems that the summit had even climbed twice. The climbing history of Monviso also includes a daring previous attempt made on 24 August 1834 by Domenico Ansaldi from Saluzzo, a surveyor by profession, which was not successful only for a couple of hundred meters. Ansaldi in fact reached an altitude of about 3,700 m but due to a block considered insuperable and the fog he decided to give up.

The upper part of the 1861 itinerary is still the current Normal route. The party started from the hamlet of Castello di Pontechianale 1605 m in the Varaita valley. This starting point was preferred over the higher Pian del Re 2020 m in the Po valley, since at that time the road didn't reach Pian del Re, ending in the the village of Crissolo at about 1330 m. After taking to the North-East the Vallanta valley, the tributary valley of the Val Varaita, they diverted towards the Forciolline lakes and stayed overnight not far from the current Bivacco Boarelli at 2835 m. The next day they conquered the summit after passing under the Colle Sagnette and climbing the south face, the today Normal route.

The following year (1862, 4th July) Bartolomeo Peyrot, a mountain guide from Val Pellice, was the first italian to climb the top. He climbed together with the Englishman Francis Fox Tuckett and the guides Peter Perrn and Michel Croz.

It was instead in the year 1863 that the first italian team summited the top of the Monte Viso. The team was formed by Quintino Sella (engineer and important politician) with Paolo and Giacinto Ballada di Saint-Robert and Giovanni Barracco, accompanied by the three local alpine guides: Raimondo Gertoux, Giuseppe Bouduin and Giovan Battista Abbà. Immediately after, in the wake of enthusiasm, Quintino Sella founded the Club Alpino Italiano (Italian Alpine Club).

1st North-East ascent: Christian Almer and W.A.B. Coolidge - july 28 1881

1st East ridge ascent: G. Rey and A. Castagnelli - August 17 1887

1st North Couloir in Winter: G. Ghigo and I. Romeo - January 25 1981

Getting There

Italian side

Access to Valle Po and Pian del Re

From A6 Torino-Savona motorway exit Marene, turn left and take the S.S. 662 towards Savigliano, continue to Saluzzo, then follow the signposts to the Po Valley along the S.P. 26 going up to Crissolo and Pian del Re 2020 m.

From A21 Torino-Alessandria-Piacenza motorway exit Asti Est, then continue towards Alba - Bra (S.S. 662) - Marene - Savigliano - Saluzzo, then follow the signposts to the Po Valley along the S.P. 26 going up to Crissolo and Pian del Re 2020 m.

Access to Valle Varaita

From the A6 Torino-Savona motorway exit Bra-Marene and take the road to Savigliano, Saluzzo and Valle Varaita (road n. 8). Once you enter the Valle Varaita, drive to Sampeyre and Casteldelfino, overcoming different villages. At the junction in Casteldelfino ignore the left toad to S. Anna di Bellino and take the road on the right to Pontechianale

Monviso Normal route

Monviso Normal Route from Refuge Quintino Sella (South side)

Difficulty: PD (Alpine scale), II+ grade UIAA

Difference in level: 1200 m from Rifugio Quintino Sella

Exposition: South

A worthwhile route up the highest peak of the Alpi Cozie

The rock difficulty doesn't exceed the III degree UIAA, but in any case the route shouldn't be taken lightly in reason of the high mountain environment and the possible presence of snow or ice even in summer after periods of bad weather. In case of snow pay attention, the face is very sliding. Along all the route from Bivacco Andreotti to the summit it's very useful to follow the yellow arrows. There are also very useful ring pegs along the climb. The standard route to summit Monviso climbs the Monviso South face – 1200 m from Refuge Quintino Sella 2640 m, difficulty II, S exposure. Here on SP the complete decription of this route: Monte Viso Normal route South face.

The approach to the Rifugio Sella starts from Pian del Re, at the and of the Valle Po. Parking fees at Pian del Re from June to October. Road always closed from November to May.

The normal route usually is climbed in two days to take it easy. Overnight stay at Quintino Sella hut must be booked in advance, because it's usually overcrowded. Alternatively it's possible to climb in 1 day starting directly from Pian del Re and overcoming a difference of level of 1800 m.

The South side where it runs the standard route can be approached also from Valle Varaita starting from Castello, a hamlet of Pontechianale and overcoming a difference of level of 2256 m

Val Varaita route report

From Castello di Pontechianale take the path leading to the Vallone di Vallanta, then leave it following the path to Bivacco Berardo where you can stay overnight. From Bivacco Berardo in 1 hour of walk, path with yellow signs, you reach the Lago delle Forciolline (at the base of the Passo Sagnette), where it stands the new Bivacco Alessandra Boarelli alle Forciolline 2835 m (12 beds, electricity, water at the lake).

Alternatively, from Vallone di Vallanta it is possible to follow the new Ezio Nicoli path, which climbs a very narrow gorge, and with a more direct route than that of the Bivacco Berardo, leads directly to the Bivacco Boarelli at the Forciolline. Surround the large lake of the Forciolline on the right following the yellow signs and continue towards the morainic basin once occupied by the glacier, heading in the direction of a reddish wall, then turn right and climb a ramp of blocks, up to the metal building of the Bivacco Andreotti 3225 m. (usable only in case of emergency).

Next to the bivouac, the marked yellow path continues, going up the little rocks to the right, towards the modest tongue of snow (remains of the little Sella Glacier). At the end of the snowy section go up a steep slope, reaching on the left some rocky ledges cutting the S wall, with red and yellow arrows to indicate the start of the route. Following the horizontal ledge to the left we soon reach a rocky wall at the foot of a waterfall that disappears in late summer. From here climb a smooth and inclined slab to reach a rocky ridge.

Turn right along rocks and small ledges, then climb left on steps, up to a rocky shoulder. Continuing north-west, you arrive at the base of a 7-8 meters high chimney, which climbs to the bottom. Continue first vertically, then diagonally to the left, up to a detrital ledge that leads to a good stopping point (called "Dining room").

Now go up along a rocky ridge, passing near the spire called "Duomo di Milano" (about 3500 m.); you overcome articulated rocks and reach the base of a reddish wall. Continue to the right along a rift, pass a slab and, bending to the left, you will gain a good terrace. The next prominence must have gone up along small chimneys ("i Fornelli"); it is an obligatory passage of II+, which can become demanding in case of ice.

You then reach a shoulder of the south-east ridge, from which the Rifugio Sella is visible. You continue passing under a characteristic gendarme, called "Eagle Head", you cross a gully (be careful in case of snow) and you earn the East ridge. Finally, turn left and, after passing the last easy ridges of the ridge, you reaches the summit.

Descent: reversing the ascent route

If you want to stay overnight at the new bivouac Alessandra Boarelli, it is best to travel the Bedale delle Forciolline which is an itinerary much more direct and saves a lot of time, cutting out the Biv Berardo. However this passage has been signaled freshly with yellow notches (with the opening of the new bivouac).

From the new bivouac it is more convenient to reach the moraine of the face glacier by climbing the debris on the orographic right of the large lake of the Forciolline, passing a convenient channel that comes out at the base of the aforementioned moraine near the old Rif Sacripante.

This path is marked with cairns. In this way you avoid the tiring stony ground that from the Passo Sagnette leads to the moraine and you save about 1 hour walk (and you have more fun).

Other routes

- Monte Viso East ridge, 1200 mt from Refuge Quintino Sella, difficulty IV, E exposure.

- Monte Viso North-West ridge, 1400 m from Refuge Vallanta (2450 mt) difficulty IV+, NW exposure.

- Punta Sella 3443 m Via Manera, 650 m from the attack, difficulty V, excellent rock, E exposure.

- Punta Caprera 3387 m Spigolo Bessone, 600 m from the attack, difficulty V, excellent rock, W exposure.

Rock climbs in the Monviso area

- Po valley – Punta Udine 3022 m Diedro Raffi, 250 m, support point. Rifugio Giacoletti, max difficulty VI, E exposure.

- Po valley – Punta Venezia 3095 m – Via dei Torrioni 350 m, support point V. Giacoletti Refuge, max difficulty V, S-E exposure

- Po-Guil valleys - Punta Roma 3070 m W face – Ti Punch route, 350 m, support point. Giacoletti refuge, max difficulty VI, W exposure

- Varaita valley – Vallone di Vallanta – Triangolo Caprera 2763 m – QuatreG route, 350 m, difficulty V+, W exposure.

- Varaita valley – Rocce Meano – Torrione 2766 Spigolo Berardo edge, 350 m + 80 easy, difficulty max V, SW exposure

Red Tape

No fees no permits required. Parking fees at Pian del Re from June to October. Pian del Re road always closed from November to May. Monte Viso is located within Parco del Monviso, recognized by UNESCO as area of the Monviso Biosphere Area della Biosfera del Monviso.

North face details

North west face

At sunrise or sunset

Monviso summits

La nebbia di Viso

This is the fog (hot and humid air) coming from Piemont during summer. The mountain can become foggy in 10 minutes.

Il Buco di Viso

The Buco di Viso or Buco delle Traversette is a tunnel carved into the rock about 75 meters long that connects Italy with France by connecting the municipal areas of Crissolo and Ristolas. It is located in Piedmont, in the territory of the province of Cuneo, on the slopes of Mount Granero, at an altitude of 2,882 m slightly lower than the col of Traversette at the altitude 2,950 m. The interior has no lighting and has an average height of 2.5 meters by about 2 meters wide, dimensions just enough to allow a loaded mule to pass through two lateral ones. The transit is free and can be easily carried out only in the summer months since the winter closure is carried out for protective purposes to prevent snow from accumulating in the tunnel obstructing the passage and causing damage to the structure.

A torch is required to walk the tunnel and a protective helmet is recommended. Inside, the temperature is significantly lower than outside.

Visolotto (3348 m)

Visolotto is a mountain joining Monviso to french border at Pointe Gastaldi

Pian del Re: Po spring and mountain flowers.

Pian del re is situated at the end of the road to Viso on the Italian side. Pian del Re is a paradise for mountain flowers.

When to climb

The best climbing period is summer. (July to September). It's easier to climb the standard route in August or September because it's possible to have a lot of hard snow on the route in early summer.

Monviso Huts

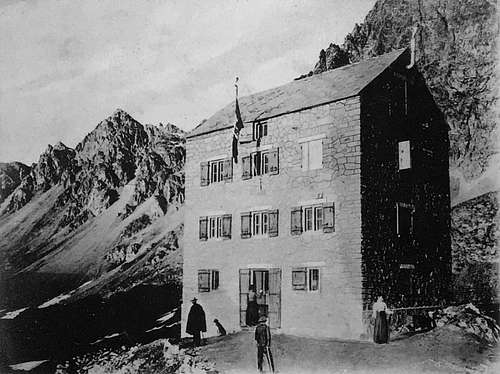

Rifugio Quintino Sella 2640 m - G.T.A. stage place

Situation: between Lago Grande di Viso and Lago di Costagrande, at the foot of Monviso

Owner and administration: Club Alpino Italiano, Sede Centrale di Milano - Cai Monviso di Saluzzo.

Guardian: CEMBRA S.a.s. di Tranchero Alessandro & C. - Via Belvedere 21 – 12034 Paesana (CN)

Persons: 135

Hut phone: +39 0175 94943 (from June 20th to September 30th)

Guardian phone: +39 0121 40534 (other periods)

Overnight stay at Quintino Sella hut must be booked in advance, because it's usually overcrowded.

Refuge du Viso 2460 m

2 and a half hours from the Roche Ecroulée, southern exposure, splendid view of the Monviso. Tour of Monviso. Tour of the Queyras

Mountain refuge (Club Alpin Briançon)

Other accomodation

The valleys surrounding the Monviso group - Po valley, Varaita valley and, from the French side, the Guil valley - offer numerous dining and accommodation options.

Mountain Conditions

Even if the mountain is easy to climb when there is not too much snow on it, altitude and wether (particulary fog coming very fast) can become very dangerous.

Take care of falling stones. Helmet is required to protect your head !

Meteo

Guidebook and maps

“Monte Viso – Alpi Cozie Meridionali” by Michelangelo Bruno – Collana CAI-TCI Guide dei Monti d’Italia

Maps

"Monviso-Valle Varaita-Valle Po-Valle Pellice" - IGC sheet 106 1:25000

"Mont Viso" - French 3637OT 1/25000

A 1898 description !

extract of :

THE ALPINE GUIDE VOL. I THE WESTERN ALPS

CHAPTER II. COTTIAN ALPS. I. SECTION 4

VISO DISTRICT

by

By the Late

JOHN BALL, F.R.S. &c.

RECONSTRUCTED AND AND REVISED BY W. A. B. COOLIDGE

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO. 1898

In the introduction of this Chapter Monte Viso was compared to the salient angle of a bastion projecting from the main watershed of the Alps towards the plain of Piedmont. This angle is so extremely sharp that, if a circle be drawn round the mountain, more then seven-eighths of the circumference will lie on the side of Piedmont, while less then one-eight will be included in the narrow valley of the Guil. The peak towers up in a singularly solitary fashion, and is therefore well seen from the Piedmontese plain and elsewhere, so that one is not surprise to learn that it is perhaps the single peak mentioned expressly by the writers of classical antiquity, while the name "Vesulus" or " Viso" has been explained by the fact that it is visible so far away. It rises a little S.E. of the main watershed, and it is noteworthy that many other of the great peaks of the S.W. Alps stands also apart from that watershed, e.g. the Punta dell' Argentera, the Aguille de Chambeyron, the Ecrins, and the other summits of the Pelvoux Group, the Grande Casse, Mont Pourri, Charbonel, Ciamarella, Grand Paradis, Grivola, &c.

The Viso is connected with the watershed by a range of shattered peaks, which include the two summits of the Visolotto, and the Punta Castaldi, or Visoulet, the exact point of junction being N. of the last-named peak. Hence the Viso is a wholly Italian mountain, and it is misleading to speak, as has been done, of its French slope. The E. face fronts the valley of the Po, the W. face overlooks the head of the Vallante valley, the S. face (that usually ascended) rising above the Forciolline glen of the last-named valley. The N. face is divided into two facets as it were, the N.W. of which dominates the head of the valley of the Guil, and the N.E. that of the Po at its source. More precise topographical details will be found in Rte. C. below. The peak itself is composed of hornblendic and other green schists, the summit being a glaucophane schist; but with these serpentine and euphotide are associated, and it is possible that the whole mass consists of igneous rocks intrusive in the older mica schists and gneiss, their schistose structure being due to pressure. Monte Viso is the culminating point of a long ridge, which runs S.E. from the main watershed, and separates the Varaita and upper Po valleys, which, together with that range, form the subject of the present Section.

A summary of the history, &c., of the Viso up to the end of 1881 is given in Mr. Coolidge's monograph on the peak in the tenth volume of the " Alpine Journal" which needs to be supplemented by Signor G. Rey's account (in the 1887 "Bollettino" of the Italian Alpine Club) of the convenient route he discovered in 1887 up the E. face of the peak. Further information may be sought in Signor Isaia's "Al Monviso per Val di Po e Val di Varaita" (Turin, 1874), though more recent explorations have caused certain portions of this work to be out of date. For the most interesting history of the fifteenth-century tunnel under the Col de la Traversette (sometimes called the "Col du Viso") Signor L. Vaccarone's admirable historical monograph "Le Pertuis du Viso" (Turin, 1881) should be consulted, particularly the appendix of original documents, a model work of its kind.

Crissolo is the best headquarters for explorers of the Viso, as it has now a fair inn and guides, and is closed to the foot of the peak. Casteldelfino does not possess the former two requisites, while Abriès lacks the last-named.

ROUTE C.

ASCENT OF MONTE VISO.

(page 61)

Monte Viso (3,843 m., 12,609 ft.) long enjoyed a reputation for inaccessibility second only to that of the Matterhorn, though this was due rather to the formidable appearance of the crags that rise tier over tier to its summit than to the actual experience of any competent mountaineer who had attempted the ascent. The S. face of the peak, above the head of the Forciolline glen, is the only side by which, looking from a distance, it appears practicable to reach a considerable height, without encountering serious difficulties, and it was this face that on August 30, 1861, Messrs. W. Mathews and F. W. Jacomb, with J. B. and Michel Croz, succeeded in effecting the first ascent of the peak. In 1862 Mr. Tucket spent a night on the summit, and in 1863 the first Italian party attained the summit. These three ascents were all made from Casteldelfino through the Forciolline glen. Nowadays, while the S. face is the ordinary route, as being both the shortest and easiest, it is usual to spent the night at the Quintino Sella Club hut (2,950 m., 9,679 ft.), at the very foot of the S. face, reaching it from Crissolo over the Passo delle Sagnette. It was not till 1879 that a new way up the Viso was struck out, MM. P. Guillemin and A. Salvador de Quatrefages then climbing from the Col de Vallante up the N.W. face, that so well seen (though wholly Italian) from the head of the valley of the Guil. But this route is rather difficult, and has been but rarely taken since its discovery, while that of the N.E. face from the Piano del Re, first effected by Mr. Coolidge in 1881, is even more difficult and dangerous, and does not seem to have been repeated. It was only in 1887 that Signor G. Rey opened out a new route up the great E. face from the Col dei Viso, and this is now frequently followed, since, without being very difficult, it is more interesting then the ordinary way up the S. face. In 1891 Signori V. Giordana and P. Gastaldi made the first ascent (4 hrs. from the Club hut up the E. wall) of the second peak of the Viso, the Viso di Vallante, 3,672 m., 12,048 ft. (the name has been wrongly applied to other points), the blunt point which rises a little S.W. of the main peak, and has been called by some French writers the " Triangle;" while in 1893 Signori Antoniotti and Grosso, having ascended this summit, forced their way first below, then along the connecting ridge in about 4 hrs. to the highest point of the Viso itself, this serving as a variation on the ordinary route.

We must now proceed to give some account of the two main routes up this magnificent peak, a brief notice of the two N. routes being quite sufficient, as their interest is mainly historical.

1. By the S. Face. - This rocky face rises above the head of the Forciolline glen, which is enclosed between the main ridge running S.E. from the Viso, and that running S.W., on which rises the Viso di Vallante. The club hut, near the Sacripante spring, can be reached in 5 hrs. from Casteldelfino by following the Col de Vallante route (Rte A. 2) as far as the Soulières chalets (2 hrs.), and then mounting in a N.E. direction, at first up a hill-side diversified with ancient knotted trees. A stream is seen on the N.E. which descends in a waterfall from the upper lakes. It is necessary to climb up the steep rocky barrier on its W. side by a green gully, and a rocky hollow, and over a shoulder, in order to gain the upper basin of the Forciolline glen. Several lakes are passed, and the glen bends gradually to the N. when the foot of the last slope of the Passo delle Sagnette is passed. The Club hut is seen as soon as the corner of the valley has been turned, and is attained in 3 hrs. from Soulières.

A party starting from Crissolo must mount in a S.W. direction by a zigzag path up pastures to the desolate Randoliera glen, enclosed between two great moraines, which leads past the Prato Fiorito lakes to that of Costagrande. Above the last-named lake there is a steep ascent up the rocky barrier called the Balze di Cesare, by which and a short descent the Lago Grande di Viso is attained.

(This point may also be reached in about 3 hrs. from the inn on the Piano de Re (see last Rte.) while a rather higher point, nearer the foot of the Passo delle Sagnette, can be attained in 4 or 5 hrs. from Crissolo or Oncino, past the Alpetto chalets.) From the large lake a stone-strewn plain is traversed in a S.W. direction to a small lake, immediately above which is the gully of shifting stones by which the Passo delle Sagnette (2,975 m., 9,761 ft.) is reached in 4-5 hrs. from Crissolo. On the higher side a stony traverse to the N.W. brings the traveller in less than ½ hr. more to the Club hut.

From the Club hut the Viso appears as a rock wall, crowned by two horns, the easternmost of which is the culminating point. Rocks and snow lead to the foot of this wall, which is then climbed in two or three great zigzags first to the E., then to the W., by many gullies and ledges, to the base of its upper portion, where the rocks, hitherto not very steep, rise more precipitously. It is perhaps best to bear rather to the right, so as to gain the S.E. ridge, but a direct ascent is also quite possible. 3-4 hrs. suffice under ordinary circumstances for the climb from the Club hut, there being no serious difficulty, though there are many loose stones on the ledges. Many inexperienced travellers make this ascent annually. The actual summit consists of a rock-strewn ridge, which rises in two horns, connected by a curving snow arête, and distant about 10 min. from each other. On the E. side and loftier point there was set up in 1896 a huge bronze statue of the Madonna, backed by a gigantic cross 6 m. (20 ft.) in height.

The view from the summit is, as might be expected from the prominent position of the peak, extremely extensive, both over the plains and the mountain ranges of Italy, France, and even Austria. It is said that on a very clear day the Mediterranean can be seen (but this seems very doubtful), and also the island of Corsica. 1½-2 hrs. suffice for the return to the Club hut.

2. By the E. Face. - The starting point for this route is a bivouac near the Lago Grande di Viso, or that of Costagrande (see above), though a party of active walkers may achieve the ascent direct from the inn on the Piano del Re. The actual ascent commences from the Col dei Viso, 3 hrs. from the inn. Immediately to the W. of that pass a great deeply cut gully is seen, which descends from a conspicuous snowfield of some size on the E. face of the Viso. The steep but good rocks about 100 m. (328 ft.) N. of this gully are climbed, and then the snowfield traversed, so as to gain the foot of the true E. ridge. A well-marked notch at the foot of the sheer drop in which this ridge ends gives access to its S. slope, by traversing which diagonally the crest of that ridge is gained above that drop, and henceforth followed more or less to the E. summit, which may be gained in from 4 to 5 hrs. from the Col dei Viso. This E. ridge is separated from the great S.E. ridge by a deep couloir which descends to the Lago Grande. The route up the E. face seems to offer no very serious difficulties, and to be quite safe.

3. By the N.W. Face - From the Piano del Re or any of the neighbouring summits there is seen to rise in the wide depression between the Viso and the Visolotto a curiously shaped and jagged rocky point, called the Mano, at the base of which is a high cliff of ice, commanding the great gully which descends from between these two peaks towards the Piano del Re. This ice cliff is really the butt end of a little glacier (the only one of any size anywhere on the Viso) which lies hidden away in a deep hollow between the two peaks, and close to the head of the Vallante glen. This small glacier (the true Viso glacier, and the real source of the Po) is the key to the two routes which have been effected up what mat be called the two facets of the N. face of the Viso. From a bivouac close to the lake just on the Italian side of the Col de Vallante there is no difficulty in reaching over stones and this glacier the notch close to the N.W. foot of the Viso. A short gully and easy rocks then lead

SIR WILLIAM MARTIN CONWAY - June 11, 1894 ascent

THE ALPS

FROM END TO END BY SIR WILLIAM MARTIN CONWAY

WESTMINSTER - ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE AND CO. 1900

THE COTTIAN ALPS (pages 34 - 41 )

A t last we started for Monte Viso from dirty Casteldelfino. It was 6.30 on as fine a morning as one might wish to see. A strong north-west wind was carrying a few blankets of mist high aloft. It seemed set and the weather must hold with it. We dispatched all the luggage we could spare and started lightly laden, up a delightful mule-path. Reaching Castello in an hour we turned up the Vallante valley. An hour brought us to Ajunt alp, where there were cows and fresh scalded milk on which we breakfasted royally.

Thus far a native accompanied us, a man with an adamant face whose expression never changed and was of the foolishly thoughtful type, proper to the White Knight in Alice Through the Looking-glass. He was the sort of man of whom you might hope to make a religious enthusiast. Once let him think he understood some mystery and he would go to the stake for his belief. He spoke to us in detached manner, as from another world. "You come from far to climb our mountains, even from England they tell me. It is very strange. Monte Viso is not like these hills. There is no grass on it. Oh! It is very big. Easy, you say; well, perhaps; it is not my affair. You will sleep in the hut. There is no wood there. You must take wood. You know that, I dare say. Well! good-day. A successful climb to you. My way lies up the valley and I shall never see you again."

From Ajut we bore up the hillside to the northeast. There was a sharp rock-peak in front, standing between the foot of the Viso and the Punta Michelis. We made for the col to the left of it, plodding steadily up a hillside diversified with broken rocks and ancient knotty trees. Squirrels played on the stones. A cuckoo called from a distant tree. A wood-pigeon quitted her nest close over our heads, and we took one fresh egg in tribute from her. Karbir climbed for it with the bag on his back and became delightfully tangled in the branches so that Zurbriggen laughed with delight.

In an hour we reached the upper edge of the tree level and paused to gather wood. Pleasant it was to see Karbir make for himself a monstrous fagot, tie it on behind his former load and then go merrily upwards as though with a mere bag of feathers.

The wind continued to rise. The increasing clouds hurried overhead and began to cling about the higher peaks. We were not destined to suffer from heat. Large rocks kept tumbling down a gully on the far side of our valley and then bounded splendidly over the débris-fan below. Another hour brought us easily to the edge of the winter snow, where we sat down to put on our pattis, whilst the unfortunate ones, who had no pattis, adjusted their gaiters. We came to little frozen lake, then to a second, and, round a corner, to a third, larger than the others and with a name of its own, the Lago Forciolline. We circled above it, along the northern slopes, with a precipice rising on our left hand. Still circling with the valley curve, we lost all view of verdant lands and wooded hills. Clouds roofed out the sky, wind howled amongst the rocks; there was nought to see but sheer desolation, with forms not large enough to be grand, not graceful enough for beauty.

At length, when the whole corner was turned, the hut came in sight, near above. Behind were the toothed pinnacles of the Viso's south arête, with one church-like rock, standing in a gap, straight over the hut. At 1.15 (after four and a half hours' walking from the inn) we stood at the door. The key was with us and all that remained to be done was to cut away the hard blue mass of ice that blocked the threshold. We hacked and hacked, urged to extra vigour by the cold wind that ran through us.

When the obstruction gave way, we entered the strong haven. A fire was lit, and the smoky chimney cured by an adjustment of the cowl. Coffee and food rewarded us and we entered on a lazy afternoon. The rattling of hail on thee roof showed how good it was to be indoors. All were marry and sang such odd snatches of song as we remembered. Sleep followed, and the hours passed swiftly, with writing for my employment and snoring for the rest. We shivered, when it occurred to us to do so, for the highest temperature we could generate in the immediate neighborhood of the stove was only 41° Fahr.

As the afternoon advanced Aymonod began to display his power as chef. He had little enough to exercise them on, for the resources of Casteldelfino are small. He compounded soup out butter, salt bread, and cheese: a combination that turned out unexpectedly well. As the pots were boiling, the men, one after another, burnt their fingers with the lids, to every one else's indescribable amusement. Thus the day rolled away. The sky cleared, the wind dropped, and a clear night came on.

June 12

I t cannot be said that we slept well in the Viso hut. I had a vivid uncanny dream that I was a Mahatma and wandered over the earth, leaving my material body in the cloak-room of a railway station. I called for it in due season but it could not be found. "Come in," said the man, "and hunt for it yourself." I found various packages and amongst them a coffin neatly done up in waterproof stuff with a green label. "Perhaps my body's in there," I said.

"Oh no!" was the reply, "they never make up merchandise in that form hereabouts. Besides, that contains the body of the man who owns these clothes," showing me the uniform and cocked hat of one of our Carabinieri friends!At 4.15 A.M., on as bleak a morning as can be imagined, we left the hut; we arrived at the summit of Monte Viso in three hours and a quarter, having only halted five minutes by the way to put on the rope. We walked at first over a hard frozen snowfield to the foot of the actual pyramid of the mountain. Turning up it, we made a long zig to the east and a longer zag back to the west, then went nearly straight up the face, striking the north arête not far from the top.

The mountain was in dreadful condition, deeply mantle in snow, which filled all the gullies and crested the ribs between them. Hot days and cold nights had turned much of it into ice. The drippings of its thaws over the rocks had glazed large areas with blue ice. The moment we touched the mountain, step-cutting commenced; we had to hew out every footing from bottom to top. Fortunately frost reigned, so that we were not troubled by slushy snow insecurely poised on ice; but many of the upper slopes were excessively steep and frail. A bitter wind blew from the start and only increased as the day advanced. When the mountain is in proper summer condition its whole south face is practically clear of snow, and the rocks form an easy staircase. " Evidently," said Louis Carrel, " Monte Viso should be like the Grivola to climb, but I have never seen a mountain in worse condition than this."

Sky and view were fairly clear when we started, but, as the hour of sunrise approached, mists began to boil in the head of the Sagnette valley and a pink glow pervaded them with a tender radiance. We rose higher and the mountain frontier to the west came into view. A cloud navy was sailing over it from France, preceded by a row of far-projecting rams. Eastwards, the Italian plains developed at our feet, spreading in purple softness to far-away undulations of peopled hills and, southwards, to Apennines piled high with masses of sunlit cumulus.

We roped in two parties, and the guides took the hard work by turns. Once, when we were leading, at the steepest part near the top, and the others were not so close to us as we supposed, our rope was permitted to start a loose stone. I looked dreamily at it, as it bounded down, and was horrified to see it making straight for Carrel, who was crossing a very bad couloir. I shouted at him and he saw it. The next instant it struck him, as I supposed, on the ear. I looked to see him stunned, but he went calmly forward. As a matter of fact he raised his elbow just in time to save his head at the expense of his funny-bone.

The higher we rose, the closer the clouds gathered about us and more the wind howled amongst the jagged rocks, as though it would tear them from the mountain side. Sooner than expected Zurbriggen turned to me and said, "In two minutes we shall be on top." I climbed beside him and saw, near at hand, a mound of snow with a foot of stick and fluttering rag standing out of its side. The high stone-man and the boxes containing the wooden Madonnas were all buried under deep winter accumulation of snow. We just had time to look down on the neighboring minor summits before clouds hid them from us. "Wait a few minutes," said Zurbriggen, "the storm may clear off at any moment, for the clouds are not thick." But just then, snow began to fall and a colder blast to blow. We turned in our steps without a word. The snow was no moment's amusement; it set in heavily and whitened the fragments of projecting rock that helped us in the ascent. It came thicker and thicker. Downward we went, incredibly slowly, retracting our ruined steps, which had all to be cleaned out once more.

The fresh snow on the rocks froze our fingers. Ridge succeeded gully, and gully ridge, with infinite monotony. At last we were below the worst of the storm and halted to eat a morsel. FitzGerald went forward whilst I remained behind, that Zurbriggen might smoke his pipe. When we started on we struck out another route and bore away to our right into a steep couloir, the main avalanche and falling stone vent off this part of the mountain. But there was no danger now; the grip of the frost was on everything. Below the couloir we emerged on the avalanche-fan, down which we glissaded and so reached the hut in an hour and half's going from the summit.

We lit the fire again and took stock of our condition, flustered, battered, and chilled. Some cold cream in FitzGerald's pocket was turned into a stony lump. Our knitted gloves were as stiff as boards. Icicles hung in rattling plenty from beards and moustachios; but a hot brew of coffee set things to rights. The day was still before us. The storm raged worse and lower than ever, so no one pushed to move.

It was eleven o'clock before we started down for Crissolo. We glissaded to the flat of the valley and thence cut steps up a short icy slope to the little Sagnette Pass, whilst the wind drove heavy hail against our right cheeks till we thought our ears would pulp. In less than half an hour from the hut we were looking down from the pass, eager to see what might be on the other side. Our guides had made minute inquiries from a local guide at Casteldelfino as to the route from the hut to Crissolo. He told them of the pass and that it was easy to climb to it, " but to descend the other side is almost impossible; there is a vertical gully there down which no man can go, and on either hand of it are walls of rock incredibly steep. You will not get down there anyway, and I advise you not to try." We were so little disturbed by these dismal tidings that we even packed the ropes in the sacks at the hut, not expecting any need for them. Nor were they required. A fairly gentle snow couloir, flanked by easy rocks, was the beginning and end of the terrors of the way. We tramped rapidly downwards and glissade carried us to a soft snow-slope.

The storm dropped behind as we descended. The Italian plain emerged, a faint vision, through a veil of falling snow; in another moment it was a clear actuality, shining in sunlight, with its lines and dots of trees, its straight ruled roads, its glittering rivers, encircled by far away hills and masses of clouds, domed and bright above, flat and purple-shadowed beneath. We pounded over wastes and slopes of soft snow and broken rock, through a region of utter desolation, where the cloud-capped crags of Viso keep watch over the frozen and snow-covered Lago Grande. Passing the end of the lake, we mounted to a second col. There was another frozen lake, the Lago Costagrande, beyond it, and more wilderness of snow and rock, whence bent away a wide and utterly desolate valley, bounded below by two huge ancient lateral moraines, monuments of a great glacier that once flowed down this trough.

But the storm was still upon our track, We hurried through a swampy region, then down sheep-pastures, and along a well-made path, bordered with flowers and all the gaiety of early summer. There the gale caught us again and flung hail and snow upon our backs, plastering them white. When the sun came out again each was a strange sight to the man walking behind him - for we were in fields where there was no sign of snow or tempest, save the foreground of whitened coat-back that hid for each a portion of the hot Italian plain. The path led us faithfully into the main valley at 2.15 P. M., we entered the Gallo Inn at Crissolo, and the interviewing of gendarmes began again. After lunch, the first decent meal we had eaten for two days, we walked to the neighboring sanctuary of S. Chiaffredo di Crissolo, a white-washed collection of buildings, finely situated, like most Alpine sanctuaries. The frescoes outside the church and the votive pictures within are miserably bad, but they served to fill up some vacant time and they led us to a fine point of view for Monte Viso. Our peak, now that it was rid of us, had shaken itself almost free of clouds. Its summit was often clear, and only tearing mist whirled about its upper rocks or was dragged through their teeth.

The gale evidently continued to blow with unabated fury; we no longer cared whether it raged or not. As we sat in the sun and looked aloft at the scene of our morning struggles we found it almost impossible to believe that less than twelve hours before we were standing together on the highest tip of that savage, remote, repellent-looking tower.

signorellil - Mar 17, 2004 3:14 pm - Voted 8/10

Untitled CommentThe unusual visibility of this mountain made it well known with ancient Romans, Greeks and (according to the tradition) even Egyptians. Some Greek legends had the garden of the Hesperides (where Jason went looking for the Golden Fleece) here and not, as now generally believed, in the Caucasus.

Leonardo da Vinci was literally obsessed by its perfect cone shape, and said it was the "perfect mountain".