-

6180 Hits

6180 Hits

-

72.08% Score

72.08% Score

-

2 Votes

2 Votes

|

|

Trip Report |

|---|---|

|

|

48.77683°N / 121.81454°W |

|

|

Jun 8, 2014 |

|

|

Mountaineering |

|

|

Spring |

Trip Report

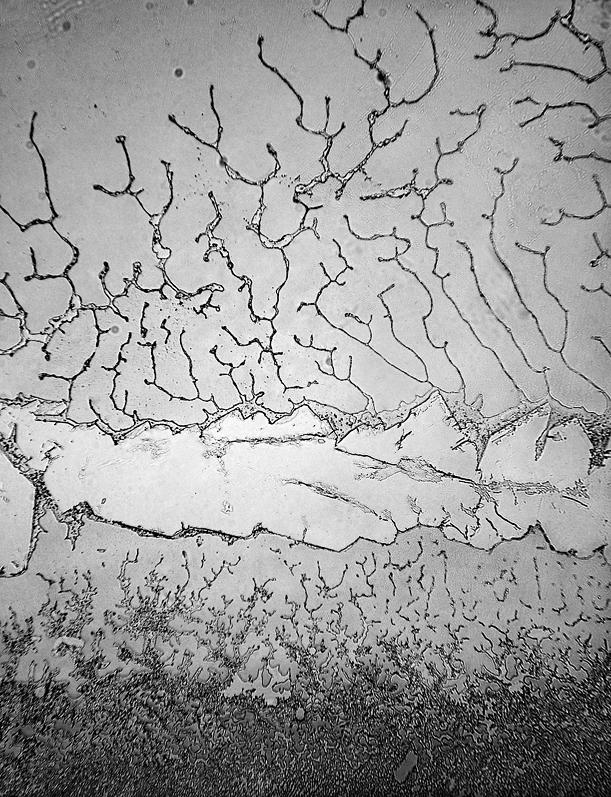

In a series of images featured in the Smithsonian magazine, photographer Rose-Lynn Fisher captured the structure of dried tears as revealed under a microscope. The look of a tear depends entirely on the circumstance under which they were shed. Tears of grief, laughing tears, onion tears, tears of "possibility and hope", watering eyes, and even "tears of elation at a liminal moment" (whatever that means) all have a distinctive appearance, each as unique as a snowflake. They also suggest landscapes as seen from an airplane. Fisher titled her work "The Topography of Tears" explaining the name in her artist's statement, "The random compositions I find in magnified tears often evoke a sense of place, like aerial views of emotional terrain. Although the empirical nature of tears is a chemistry of water, proteins, minerals, hormones, antibodies and enzymes, the topography of tears is a momentary landscape…like an ephemeral atlas." During the eleven weeks of the 2014 Boeing Employees Alpine Society Basic Climbing Class (BOEALPS BCC) the students and instructors of The Summitears team traversed this "topography of tears" on their challenging three month long journey to the summit of Mount Baker.The Summitears' path to the summit of Mount Baker started in February with a timed fitness evaluation hike up Mt Si and spanned another ten weekend outings to diverse destinations across Washington State: Kirkland's St Edwards Park, Mount Erie near Anacortes, Stevens Pass, Snoqualmie Pass' Commonwealth Basin, The Duke of Kent near McClellan Butte, Mount Washington in the Olympic Mountains, Leavenworth, the Tatoosh Range near Mount Rainier, the Nisqually Glacier on Mount Rainier, and volunteer trail work in the Wild Sky Wilderness. The class' one hundred students and instructors were broken up into eight teams of twelve. Our team designation was Team 7, but every BCC team is supposed to pick a name and make team t-shirts. The name should be "organic", developing from the experiences of the team over the class. Most of the early names thought up for Team 7 were funny, but not fit for printing on t-shirts, ranging from the bizarre, toilet humor, and the obscene. As the team lead instructor I had to put the kibosh on those ideas no matter how much they made me laugh. Like the other proposed names, Summitears was a joke, concocted over beers at Icicle Brewing after the Leavenworth rock climbing outing, but this was the first one proposed that we could print on a t-shirt without violating Boeing Employees' Clubs policy. Student Dana suggested the name because she had cried a few times during the class and we had all experienced the disappointment of not achieving any summits at that point in the class. Up to our first successful summit (Lane Peak in the Tatoosh) our working title team name had been the "Saddle Baggers" (as opposed to "Peak Baggers") because we kept making it only to saddles below peaks before having to turn around. Our other team working-title team name was Team Subaru because almost everyone on the team drove a flavor of Subaru and our trailhead photos usually featured us clustered around an Outback. We thought we should have been sponsored for all that Subaru advertising we were generating. Hey, Subaru if anyone there is reading this we're still waiting for that check!

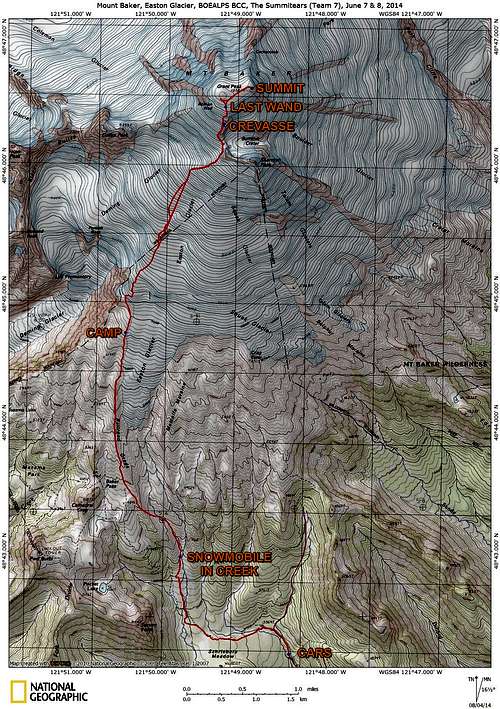

We all hoped to windup the class with a bang instead of a whimper, but whether or not we would end the class standing on the summit of Mount Baker would all depend on the weather. I had climbed Baker before, but my first summit took three attempts; the first two attempts were thwarted by fierce storms. The weekend of the graduation climb the weather forecast was right on the edge and could have been a problem, partly cloudy with a chance of snow—the kind of forecast in the Northwest that means be prepared for anything from precipitation to sun. We drove up Saturday morning via Highway 20 and the Baker Lake Road. The forest service road was snow covered about a quarter mile from the trailhead. As far in as we could drive there were an insane number of cars lining the road, more than I have ever seen parked at this trailhead. Just finding a parking spot was our first obstacle to the summit. It seemed that everyone and their cousin decided the first weekend of June was the perfect time to climb Baker. It was not only hordes of climbers we would be sharing the mountain with, but snowmobilers too. All day Saturday they were roaring up and down the trail, even tearing around on the glacier too. Traffic congestion, exhaust fumes, crowds—it was not quite the wilderness alpine climbing experience I would have hoped for. It was what you usually go to the mountains to escape. A lot of groups were out that weekend: Washington Alpine Club (WAC), Skagit Alpine Club (SAC), American Alpine Institute, and One Step at a Time's Glacier Climbing Class (OSAT). There were also tons of backcountry skiers and snowboarders. We camped high next to the WAC group and the OSAT camp was not far away. Between the WAC and the OSAT campsites there were so many tents that it looked like photos of the Everest Base Camp. In most of the areas where there is interesting climbing backcountry permitting rules limit group sizes to a maximum of twelve persons, that's why BCC teams are structured to have a dozen students and instructors total. However, the Easton Glacier is one of the few areas in the state where that restriction does not apply.

Mount Baker is enmeshed in a torturous jumble of jurisdictions: Mount Baker National Recreation Area, Mount Baker Wilderness, and the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest. You park your car in the National Forest, most of the approach hike and climb are in the National Recreation Area, but the summit is in the Wilderness. The one major jurisdiction Baker does not fall under is the North Cascades National Park. Nearby Mount Shuksan is in the National Park, but Baker is entirely outside of it. The Recreation Area covers the entire Easton Glacier all the way up to Sherman Peak near the base of the Roman Wall. Since it is a Recreation Area, wilderness limits on group size do not apply, hence all the big groups on Baker. Another consequence of this is that snowmobiles are allowed in Recreation Areas, so on the way in you have to share the trail with them and during the day hear and see them tearing around on the Easton Glacier. The Recreation Area does not extend to the summit, so in theory snowmobiles are not allowed up there, but reportedly that has not stopped some people from riding all the way to the top. Riding a snowmobile on a glacier seems crazy to me and I have heard that in past some snowmobilers have fallen into crevasses.

Our original plan for the team's graduation climb was Eldorado Peak, but we had a lot of injuries on the team: three sets of bad knees, one bad back, and one bad ankle (another proposed team name: The Walking Dead). I decided the steep and treacherous approach hike (especially the boulder field) to Eldo would be too tough and the risks of injury too high so I switched our graduation climb to Baker. BOEALPS BCC Team 4 was already planning on climbing Baker that weekend via the Coleman/Deming route so that left the Easton Glacier route. I did not mind returning to Baker, I have climbed it three times before and it was a good opportunity to share my experience. I grew up in Bellingham so I consider Baker my "home" mountain; I learned how to snowboard at the Mount Baker Ski Area Area and the first mountain I ever climbed was Baker's next door neighbor Mount Shuksan. I was a BCC Team Lead this year, but a dozen years prior I had been a BCC student and Baker had been my graduation climb. Also, most of the students were taking the class because they wanted to climb Mount Rainier and Baker is great training for Rainier. Just like Rainier, Mount Baker is a heavily glaciated volcano climb. On a Baker climb you will encounter every challenge you will experience climbing Rainier except for the effects of higher elevation. The two popular Baker routes also have their equivalents on Rainier. The easier approach and heavy traffic of the Camp Muir/Disappointment Cleaver route on Rainier is similar to the Easton Glacier route while the less busy and more wildness feel of the approach hike to Camp Schurman/Emmons Glacier is comparable to the Coleman/Deming route on Baker. In both cases, even though Rainier is much taller than Baker the summit day is approximately the same, four thousand feet of elevation to the top.

From the trailhead we hiked through Schriebers Meadow and then headed up via the Railroad Grade trail. The Railroad Grade is a natural feature, but it really does look like a perfectly graded railroad berm. Along the Railroad Grade we heard the whistle of marmots and saw many of them scurry off the trail as we approached. We did not see any other wildlife all weekend, but I did see fresh bear prints in Schriebers Meadow. The hike in was uneventful and we camped not far from the WAC group around sixty-five hundred feet near the area called "Portal Camp" on my map. It had been sunny when we started the hike in and we had clear views of the summit, but by the time we arrived in camp clouds had rolled in obscuring our view of the upper mountain. We got to camp in the early afternoon so had plenty of time to build tent platforms, wind walls, and a large camp kitchen. The plan was to wake up at half past midnight so everyone was in their tents in the early evening. When you crawl into your sleeping bag for an alpine start while it is still light out sleep is hard to come by, so the best you can hope for is to rest and lightly doze. I brought a book and read for a few hours before drifting off into a fitful slumber. Everyone went to sleep hoping that the weather would cooperate when we started our climb to the summit the next day. Weather is the single biggest factor for a successful Baker climb. As I mentioned before my own first two attempts to climb Baker were unsuccessful, in both cases we were weathered off the mountain. Prash, The Summitears' senior instructor, told the story of a his experience instructing a 2005 BCC Baker graduation climb where they got caught in a storm so violent that it destroyed tents and they had to retreat from the mountain in the middle of the night.

The Summitears were up at oh-dark-thirty for an alpine start. Thankfully when we woke the sky was clear and full of stars in the dark moonless night. As we were getting ready a long line of WAC rope teams headed past our camp, summit bound. I knew the WAC was getting up at midnight. I intentionally staggered our start time hoping that the WAC would have a big enough head start that we would not get stuck behind them, but they were a large group so we eventually caught up with them and ended up following them to the summit. The entire WAC Basic Climbing Class was on Baker and they had something like a dozen or more rope teams heading for the summit. Their group had been faster hikers than us on the way in from the trailhead so I hoped we wouldn't get stuck behind them. However, with that many rope teams it is just one of those things that all the small inconsequential actions that slow a single rope team down add up and ripple down the line so that everyone goes collectively slower. We headed out of camp without crampons on because the freezing level had been forecast for ten thousand feet overnight. We did carry them with us and around eighty-five hundred feet the snow was firm enough that we needed crampons and we stopped for a quick break to strap them on.

You could not see them with the unaided eye, but the morning of our Baker summit the Northern Lights were putting on a show visible to cameras set for long exposures. One of the members of the Skagit Alpine Club had set up a camera pointed at Sherman Peak set to take a series of time-lapse photos and inadvertently captured the Northern Lights in a video they posted on YouTube (see links section below). I was camped in the same area the summer before as a student with BOEALPS Intermediate Climbing Class for our Ice Climbing outing. One of my fellow students took a photo then that was a lucky accident and also captured the Northern Lights. He did not know the Lights were there either; he was just trying to get a photo of stars over Baker.

I was in the front of the lead rope and in addition to all the other gear I was carrying I had a large fascine-like bundle of bamboo lashed to my pack. Every hundred feet or so I would stop and reach over my shoulder to draw one of the three foot long bamboo rods from my quiver and plant it in the snow with the ribbons of fluorescent surveyor tape lashed to one end fluttering in the wind. I was setting wands, which we brought with us to mark our trail from camp to the summit. Wands are typically made from bamboo garden stakes with strips of fluorescent surveyors tape securely tied to one end. When placing wands the climber at the front of the lead rope team securely plants a wand in the snow. When the last person on the same rope team reaches that wand they shout out, "Wand!" Then the climber in front places another wand the idea being to space wands out no more than a rope length apart. In a white-out if you can not see your next want the end person on the rope team will stay at the last known wand while the climber at the front will walk back an forth at the full rope length until the next wand is located. In bad visibility this allow rope teams to find their next wand because they know they will always be spaced no more than the length of their rope apart. Based on the length of a sixty-meter rope we calculated that we would need seventy-five wands. That was accurate, assuming the lead rope team would use the full length of the rope, but day of the summit one of the instructors was not feeling well so we ended up with only ropes teams of three instead of the rope team of four we calculated for. This meant we were setting wands at slightly shorter intervals since we shortened the ropes for rope teams of three. Our wands were exhausted at the top of the Roman Wall just below the summit area.

We knew we would need wands for Baker because even if the forecast was good because the weather can be unpredictable on the mountain. That weekend the forecast was right on the edge of bad, but even if the forecast was favorable it is still a good idea to bring wands in the car and decide at the trailhead if they are needed. Mount Baker is so heavily glaciated that it creates its own weather. The same thing happens on Mount Rainer. If you live in the Seattle area you have probably seen the summit of Rainier wrapped up in a cloud cap on an otherwise sunny clear blue day. The cloud cap is a function of all that snow and ice on the mountain interacting with humid air to creating localized clouds. Excluding Rainier, Baker's glaciers contain more ice than all the other Cascade volcanoes combined. Baker's one dozen glaciers add up to forty-four square miles of ice. By comparison Rainier's massive glaciers only add up to thirty-five square miles of ice. Although only the fourth highest summit in Washington State, Baker gets massive amounts of snow every winter, in fact the ski area set the world record for recorded snowfall; 1,140 inches in the 1998-99 season. Summitears' instructors Charlie and Prash had both been BCC students in 1999 and said it was a tough year for the class. The heavy snow had been Cascades Range wide and no one in the BCC summited anything that year including that year's Baker graduation climb.

As we as we trudged step-by-step upwards to the summit clouds rolled in, a dark menace blotting out the stars above us. Visibility would come and go as waves of cloud cover washed over the mountain, validating our decision to set wands. We were about half way up the mountain as day broke. Dawn revealed Baker resting above a sea of clouds. If it had been clear we should have been able to view the sea. As the crow flies Baker is less than thirty-five miles from tidewater and on a clear day the views from the summit are epic, encompassing the North Cascades and the Salish Sea. Baker is close enough to Bellingham Bay that there is an annual multi-sport relay race that starts with cross country skiing at the Mt. Baker Ski Area and ends with sea kayaking across the Bay. Growing up in Bellingham, I peddled a road bike in my first Ski to Sea in 1989. Two weeks before The Summitears' graduation climb I was back, riding in the Ski to Sea mountain bike leg.

On the way to the summit we passed under Sherman Peak and could smell the rotten-egg sulfur smell wafting up from Baker's steam vents in Sherman Crater. Though Baker is a dormant volcano it is still semi-active and could erupt some day. After passing Sherman Peak we reached the base of the Roman Wall, the steep final approach to Baker's summit. It was a bit of a traffic jam at the Roman Wall with all the people going to the summit at the same time. I joked the day before when we saw all those cars at the trailhead that the Roman Wall would be our version of the Hillary Step, the notorious choke point near the summit of Everest that you read about in so many accounts. It did in fact turn out to be a bottleneck,but in our case the Roman Wall is wide and we always had the option of going around the main groups, but at the price of having to break our own trail. The one open crevasse we encountered was about two-thirds of the way up the Roman Wall. It was wide enough that we had to make a small jump to cross it. It is always a relief to safely cross a crevasse. On the other side I spared a moment to glance down I could see that it was deep and dangerous looking. As part of the class we train for crevasse rescue, but of course you hope never to have to use those skills. Cheryl, one of The Summitears' instructors did not have to speculate about what a crevasse fall would be like, she had experienced it…on Baker. Cheryl's story of her 2007 crevasse fall is included at the end of this trip report.

At the summit we got very lucky with the weather. People at the top of Baker just before us were in a whiteout and told of wandering around lost, looking vainly for the summit. The summit of Baker is huge. Once you crest the Roman Wall you still have a quarter mile hike across a broad flat area known as the "Football Field". The true summit of Baker is a small knoll called Grant Peak at the far end of the Football Field. We dropped our packs at the base of Grant Peak and hoofed it up to the top to bag the peak. The summit is a couple hundred feet shy of eleven thousand so it is just high enough that you start to feel the effects of elevation. In that thinner air we were all slightly winded just scrambling up Grant Peak. The summit elevation is one of the many features that makes Baker a fun climb and a good stepping stone to Rainier. Right when you get to the elevation where the climb starts to get really grueling you are on the summit.

If the names of Baker's two peaks, Grant and Sherman, ring a bell from high school American history classes it's because they were named after Civil War generals. Baker was first climbed in 1868, three years after the end of the Civil War and the peaks were christened in honor of the two most famous generals who served on the Union side. Over half the Summitears' students were from Australia or New Zealand and were not familiar with Civil War history. I am a history buff and there is nothing I like more than the sound of my own voice droning on about history, so I was giddy at the opportunity to bore to tears The Summitears' ANZAC team members with a lecture about the American Civil War.

After a round of the usual congratulatory high fives and summit photos we turned around for the long hike down the mountain. We did not spend too much time on the summit, even though it was sunny and clear it was still windy and cold. Hiking back across the Football Field we finally linked up with Team 4, the other BCC team climbing Baker that weekend. They had ascended the mountain via the Colman/Deming route and we expected to see them at the summit. The Football Field is so big and there were enough people up there so we almost missed them.

As we were heading down the mountain we passed a lot of skiers and snowboarders heading up for the summit. Skiers start a little later than climbers on foot because they want softer snow for the descent. I was very jealous; I would have loved to ski out. Six years ago I switched from snowboarding to skiing so I could get into backcountry skiing. The main reason I got into backcountry skiing was because I have been on enough climbing trips where I have run into skiers and I kept having the thought, "Why am I walking out when I could be skiing?" The next time I stand on Baker's summit I will be on skis.

Like a lot of other peaks that I have climbed multiple times Baker has shrunk over the years. Not literally of course, but my perception has changed. The first time I summited I did not have much alpine experience to judge the mountain by and it seemed a daunting task to climb it. Ironically my accumulated mountaineering experience did not prevent me from being the one person on our team to vomit. Although I no longer perceived Baker as the same challenge I once did it still remained physically demanding. If you live at sea level and quickly ascend to elevations above eight thousand feet you are going to be susceptible to altitude sickness. One of the students and myself were both feeling it at the summit, but I got the worst of it on the descent. Prior to the graduation climb I had a long week so I went into the climb already exhausted. When we took a break at the bottom of the Roman Wall for a snack, the food I was eating (bagel bites with cream cheese) did not agree with me and came right back up. I do not think that was the most inspiring sight for the students to see their team lead doubled over throwing up, but I comfort myself with the thought that I was providing effective instruction with a useful object lesson in the effects of altitude.

It was another good year in the BOEALPS BCC. It was great to see a group of students go from no alpine experience to climbing Cascade volcanoes. For the instructors we all learned a lot too—that is why we all volunteer, we get as much out of it as the students. I has been my experience that the best way to cement the skills I learned as a student was to return as an instructor. I learned a lot as a team lead too, it’s a management job, and it gave me a lot more respect for anyone in a management role—in the mountains or otherwise. The BCC is a big commitment and completely takes over your life, after the class I hung up my ice axe for almost two months. I was burnt out and needed to attend to all the things in my life I put on hold for the three months of the class. Then before I knew it, half the summer was gone. Holy crap—I need to get out and climb ASAP!

Crevasse Rescue Practice

Several weeks before the graduation climb the class was on Rainier's Nisqually Glacier for crevasse rescue training. One of the most important skills outing in the BOEALPS BCC is crevasse rescue. Crevasses are large cracks in the glacial ice that are often hidden by snow like pit traps. They are one of the hazards of mountaineering. If a member of your rope team falls into a crevasse you need to know how to pull them out quickly. For the class, students take turns being lowered into a crevasse. The student in the crevasse practices self-rescue techniques using prussiks to shimmy up the rope while on top of the glacier their teammates set up "z-pulley" systems to haul the student in the crevasse to the surface.

We met at the Paradise parking lot at half-past six in the morning and hiked up to areas on the Nisqually Glacier where there are good open crevasses suitable for practicing rescue techniques. It was one of those Boealps days where the weather left a lot to be desired. The forecast was in the neighborhood of an eighty percent chance of snow. I faced the day with a type of grim resolve I reserve for bad-weather day BOEALPS outings. The day started clear, but quickly deteriorated to near-whiteout conditions. In the BCC there is no such thing as cancelling because of weather. The only concession Boealps ever makes for the elements is to change destinations if the avalanche danger is too high. Most of the day was bitterly cold and windy, but occasionally the wind would stop and it would brighten up which was almost as bad. The fog surrounding us would suddenly heat up to sauna temperatures and it would get uncomfortably warm in the steam bath conditions. Just when you had unzipped your jacket to cool down it would darken again with the wind, snow, and cold returning. During the class a lot of the team said they preferred it inside the crevasse to topside.

All of our educational goals were achieved: the students got a turn in the crevasse and in the near white-out conditions we got a very practical application of the value of placing wands to mark our trail back to the parking lot. It was a long day, I was up at 3:30 a.m. so I could meet my carpool and make it to Rainier by 6:30 a.m. We started hiking at 7 a.m. and did not get back to Paradise until 6:30 p.m.—soaked and exhausted. That meant getting home after 10 p.m. on a Sunday evening. I went directly to bed without a shower and leaving a pile of wet gear in my living room so that I would not be a wreck at work on Monday—the life of a weekend warrior.

Team t-shirt

Timeline & Map

| Saturday, June 7th | ||

| 6:30 a.m. | — | Leave Seattle |

| 8 a.m. | — | Hwy 20 & Baker Lake Rd. |

| 9:15 a.m. | — | Leave Cars |

| 1:45 p.m. | — | Arrive Camp |

| 6:30 p.m. | — | Go to sleep |

| 9:10 p.m. | — | Sunset |

| Sunday, June 8th | ||

| 12:30 a.m. | — | Wake up for alpine start |

| 1:45 a.m. | — | Walking |

| 4:15 a.m. | — | Stop to put crampons on |

| 5:08 a.m. | — | Sunrise |

| 8:15 a.m. | — | Grant Peak (Baker Summit) |

| 12:45 p.m. | — | Back to Camp |

| 2:20 p.m. | — | Leave Camp |

| 5:15 p.m. | — | Back to Cars |

Cheryl's 2007 Crevasse Fall

In 2007 Cheryl was an instructor for another BOEALPS BCC Mount Baker graduation climb on the Easton Glacier. On their way to the summit she experienced the thing that we all train for but hope will never happen: a fall in to a glacial crevasse. The story is told both from Cheryl's perspective in the crevasse and from up top from the perspective of the student immediately behind Cheryl on her rope team.Cheryl's Story

Well......I've verbally told this story in pieces, but haven't written it down, so I'll give it a shot. This is the extended version and from my point of view where I was located. I'm sure there are other details I missed being "away from the team" at the time of the incident.

We got up at 1am to climb. It was warm and clear in the morning. John had intended to lead our group, but he was helping someone on their rope tie in, and our all-women rope team was ready, so we decided our team would lead up the glacier. We headed up about 2:20am behind another 2 rope teams from Bellingham Christian School who had a leader from Belllingham Mountain Rescue (most of the people on their team had not been up a mountain before, but had trained in the previous weeks for this climb).

We crossed a HUGE debris field (with chunks of snow and ice as large as minivans) apparently from a large cornice that had broken up above around 8000 ft. We stepped and hopped over a few smaller crevasses, when the rope teams ahead started to slow down. Around 4am, I heard from above there was a "2 ft" crevasse everyone up above was having to jump, so I got on the radio and informed the team. As I approached I saw a large crevasse spanning what seemed to be the entire width of the glacier. I saw a woman last on her rope jump and land on her chest on the other side. I hear loud cheers and whistles congratulating her. Then I saw an UNROPED foreign climber (with a German accent) jump right after her, almost on top of her. They both made it as did the remainder of the two rope teams before them.

I approached the crevasse and thought, "HMMM...that doesn't like like 2 ft to me....more like 4+ ft" as I looked down into the black, gaping crack. I had jumped some crevasses before, but not quite as wide as this one, although it looked feasible. It was around 4am and dark. From what I could see, the width of the crevasse on either side looked wider than were the team had just been jumping. I felt the safest spot would be to cross where the 2 rope teams and UNROPED climber had just crossed, since it was unclear how stable the rest of the lip was. I looked back at Kelly, the student behind me on the rope, and she must have read the look on my face. She had given me enough slack to jump across the crevasse but was crouched down and held her ice axe ready to arrest.

Everyone was jumping from a small platform approx 1.5 X 1 ft in diameter which was lower than the rest of the lip and lower than the other side of the crevasse you had to jump to. I tried to visually assess it's thickness, but it was difficult leaning over the crevasse. I could see packed footprints there, so I stepped down onto them. I mentally prepared and physically crouched down and jumped. I knew I could make it to the other side. That is......right before the snow from beneath my feet collapsed (I was told by those watching) and the momentum from my jump sent me head first into the crevasse. It happened so incredibly fast. There was no time to think or to react. I was falling and even though my eyes were open, I saw only blackness. I felt my helmet hit the side of the crevasse as I plunged. I felt weightlessness, and then just as fast, the yank of the rope on my chest harness which swung my body upright. Kelly caught me!! (I love that gal!!).

I looked around and thought "HOLY @%^&*!!!" That didn't just happen, did it???" I was about 45 feet down inside the crevasse. It was about 10 ft wide with smooth blue sides and a bottom that slowly narrowed and appeared to go to infinity! I had a radio on the front of my pack's chest strap which amazingly didn't fall off and I radioed that I was OK. I checked my harness and figure eight a few times and then I noticed a locking biner on my harness wasn't locked! I didn't move an inch, then slowly locked it. I thought ,"Wow, how lucky that I fell with an unlocked biner and didn't fall off the rope!". Then, silly me, I realized there was nothing in the biner---I had a rewoven figure-8 around my harness-remember?! Whew!! Someone from the Bellingham team yelled to me to put on more clothes to keep warm. I said I was OK. I didn't feel cold.

I heard Heather from our rope team radio "Caroline just fell inot a crevasse!!". I radioed back. "No, it's Cheryl. Cheryl's in the crevasse." I was pretty sure of that, unfortunately. I said calmly and clearly "Please don't drop me," then, "Please set an anchor." I tried to dig my ice axe into the wall of ice in front of me to no avail. I felt a bit anxious, but remained surprisingly calm.

I didn't want to move around since I didn't know how precarious the situation was above. I remember the students getting pulled a few feet during crevasse rescue the week before when people started to weight the rope as they prussiked. I didn't want to mess with that rope I was dangling from since I didn't know how stable my "anchor" was, so I tried to remain still. I looked around and thought, "Hey, my camera is still attacked to my hip belt". I made sure my ice axe was secure and grabbed my camera. It was hard to look up because there was constant water dripping on me from the above lip, but I pointed the camera and shot. I looked down only a few times. It was appearingly endless below, so I held the camera out to the side, but the camera wouldn't focus and click. That was the last time I looked down.

I hung out for a while. I felt my body drop a few feet suddenly! I hopefully assumed that was them up above transferring the weight to an anchor??!! Some time went by. My legs started to tingle and then go numb. It was a little disconcerting, so I tried to stretch and flex them. I radioed up to see if I could get an update. "I'm sure they are busy trying to set up a rescue system", I thought. A few more moments went by and John radioed that the other team was going to send a separate rope down for me to tie into and they would pull me up with that since the rope I was currently tied to was firmly entrenched into the snow. I guess they had already tried to pull me up with brute force, but the rope wouldn't budge (I guess I shouldn't have eaten those rice krispy treats!!) Then I looked up and saw a few people pass over top of me to the right. They didn't look down at me or ask, "Hey how's it hangin'?" or "How's the view?" or anything else. I heard later they were on the way to the summit and felt it would have taken too long to help out.

John started to clear the lip of the crevasse. Chunks of snow were coming down to the left side of me. Some started to hit my head, so I yelled up. I was nervous the entire lip might collapse on top of me. I guess even though I could see John when he leaned over into the crevasse, he couldn't see me. A few more moments passed and the most BEAUTIFUL orange rope I had ever seen started to get lowered towards me. It even had a figure eight tied in the end of it--"YES!!!" I clipped it to my locking biner, locked it, and took a breath. I secretly hoped I would be pulled up on the side I jumped from, so I wouldn't have to jump that *&%! crevasse again!

They started to pull me up from both sides. I came up very fast!! Before long, I was being pulled into the overhanging lip of the crevasse where the rope had entrenched. My body was completely up against the snow. I quickly asked for some slack. I swung back out over the crevasse. I was surprisingly out of breath and asked John to take a few seconds break. Then, they pulled me SLOWLY towards the lip and I was able to get my legs up over the overhanging snow. As I was ready to be pulled the last few feet to freedom, the team on the other side kept pulling. They were pullling me back into the crevasse! I hurriedly asked if they could give slack, but they kept pulling me back! Then, finally, some slack in that rope. John grabbed my ice axe which was around my wrist as his headlamp fell of his helmet and quickly down into the crevasse. "Better the headlamp, tham me, I thought!" The team pulled and I ended up belly down in the snow at the feet of my teammates!! Mission accomplished!!

I stood up and walked a few feet forward. I looked back and smiled and waved (feeling something akin to Miss America) to the Belligham team. The UNROPED climber approached and gave me some words of wisdom, "You know, you really shouldn't jump a crevasse if you don't think you can make it to the other side!" I replied, "OK, thanks!", with gritted teeth. I conveyed my email address to the Bellingham folks.

John gathered the team and asked if people wanted to still try to summit or head down. At least one member wanted to still push on. John felt we had enough "excitement" for the day, so we headed back to camp, rested for a bit, then packed up and headed back to the cars. I breathed steadily as I walked over the remaining "small" crevasses.

I ended up with just a swollen left hand and bruised right shoulder, presumably from the fall on the way down. Kelly, my HERO/HEROINE who arrested me, ended up with a badly bruised arm and was found a few nights ago ice ace arresting in her sleep.

Kelly's Story

Not too long after we crossed the avalanche debris field we were climbing we got word that there was a 2' crevasse jump. We were stopped for a bit waiting for other teams to make the jump.

When Cheryl approached the edge she was clearly making a through check of the area. I started to think this must be serious, I checked the rope to see if there was enough slack (but not too much) for Cheryl to jump and thought it looked good. Just before she jumped she turned and looked and me. She didn't look afraid, it looked like she was taking the jump very seriously and was checking to see if I was prepared.

In response to her look I brought the ice axe up in my hands and crouched down, I wanted her to see that I was prepared to arrest immediately. I said "it's ok Cheryl I've got you". I meant it. I felt/knew I could arrest her.

As soon as I saw her helmet drop down and not across I shouted Arrest! Arrest! Arrest! And threw myself on the ice axe as hard as I could on the ground (hence the bruises). A millisecond after I hit the ground I started to get drug, very fast, toward the crevasse, I closed my eyes because snow was flying in my face from the ice axe being drug thru snow. I thought "I've got to stop her or I'm going in" and just kept digging down and pushing on the ice axe for all I was worth. During window of time before she jumped and while I was arresting I knew/felt 100% I would stop the fall.

When I stopped I was face down in the snow with the chest harness pressed against my neck and the rope from the chest harness pulling across my wrist below my thumb towards the crevasse. I was pulling the rest of my wrist, fore arm and arm down and towards me on the ice axe. I kept pushing down on the ice axe after I stopped. The tork of two different directions on my wrist hurt like crazy. At that point, in my head it felt like the ice axe was barely sunk in the snow and that the arrest could fail at any minute and if the arrest didn't fail then my wrist would snap and then the arrest would fail after that.

The first voices I heard were the B'ham people on the other side of the crevasse say "Somebody just went in" They started to yell to Cheryl, and very calmly told her to put some clothes on, I yelled back to them that her name was Cheryl and she was an instructor. I heard them repeat that information to each other. They started talking to you again, this time calling you by name. I heard them ask if they should set up a z-pulley I said "Yes!! Set up a z-pulley!!! I need help!! I barely have her!!"

I turned my head and looked down the rope at Heather and yelled "I need help!! I saw that she was had arrested and was still in arrest position.

I heard a voice of a guy (I couldn't see who it was) say: "You guys need any help here?" the voice was from our side of the crevasse and I yelled "Yes!! I need help!! Somebody help me!! I need an anchor!! I barely have her!!"

Then the German man apparently had jumped back over the crevasse and crouched down be side me and to see what he could do and I said "Get this rope off my wrist, you've got to get this rope off my wrist". So he sat next to me and lifted the rope off my wrist about an inch and held it up off my wrist. That was huge relief and my confidence that I could hold the arrest longer returned. I asked the German guy, "How far away from the edge am I?" and he replied 4 or 5 meters.

Unknown to me the guy that asked if we needed help had started to put in an anchor.

Still thinking that no one had started in on an anchor I started yelling for John. I yelled "Where is John!! Get John up here! John!! John!!" I heard Barry's voice and I turned my head and saw he and Bruce had come up along side of us about 10' away. I saw Barry was getting out his shovel and I yelled "Barry come dig me an anchor I've got to get up! I've got to get up!" Barry didn't look at me; he said later he did not hear me. I heard John yelling to Barry and Barry yelling back to John.

The German man turned behind me and said to someone "She's got to get up, can she get up now?" And I heard a voice say "Ok, you can get up but very slowly". I turned my head around to look behind me and saw a picket on either side of the rope. Each picket had a prussic and a carabiner. And a guy was standing over the anchors watching me. I realized he must have been the person who asked if we needed help. So, I slowly transferred the weight to the anchor and noticed I couldn't stand up because the chest harness had me pinned to the rope which was pinned to the snow. I unhooked the chest harness and was able to get on my knees, and then I dug out the snow from under my feet with my axe a bit so I could stand.

When I stood up I noticed John Alley at the edge of the crevasse communicating with the b'ham team. I was still in the rope looking around at what was going on and thought "I want to tie into the anchor" I started reaching for a 'biner and a sling. As I grabbed them people started to line up behind me to pull Cheryl blocking my way to the anchor, I heard John say to get ready to pull so. I put the 'biner and the sling away and got ready to pull.

When John told us to get ready to pull, since I was at the front of the pull line I turned and repeated it to everyone behind me (even though they could probably hear John too). I told everyone we would pull on three so when John said to start I yelled "1-2-3 PULL" and repeated it (until we apparently pulled Cheryl into the cornice) then we gave her slack and pulled again (in conjunction with John coordinating with the B'ham team and with no help from the team that was jumping over Cheryl to continue their climb), until she was out.

I stood there looking at the Cheryl just out of the crevasse and John Anderson walked over to me and told me to put some additional clothes on. So I did.

Cheryl's comment: "I'm glad I couldn't hear Kelly from below about the "I've barely got her!" part!! Something to be said about the deafening silence of crevasses.

Links

The Microscopic Structures of Dried Human Tears

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-microscopic-structures-of-dried-human-tears-180947766

Ellinor, a trip report in verse

www.summitpost.org/ellinor-a-trip-report-in-verse/908526

The Summitears' first class overnight trip to climb Mounts Washington and Ellinor

2014 BOEALPS Basic Climbing Class Slide Show

http://vimeo.com/gnarlynorthwest/2014-bcc-slide-show

Boeing Employee’s Alpine Society

http://boealps.org/

Although Boealps is a Boeing employees’ club, classes and volunteering are open to non-Boeing employees too.

The Washington Alpine Club

http://www.wacweb.org/

Skagit Alpine Club

http://www.skagitalpineclub.com/

Mount Baker Northern Lights recorded by the Skagit Alpine Club

http://youtu.be/Zh9mI6JXuw4

One Step at a Time

http://osat.org/

Outdoor club & AA group

American Alpine Institute

http://www.alpineinstitute.com/

Ski to Sea

http://www.skitosea.com/

Mount Baker to Bellingham multi-sport relay race. The legs include: cross country ski, downhill ski/snowboard, running, road bike, river canoe, mountain bike, and sea kayak. There is a documentary about the Ski to Sea history:

http://www.themountainrunners.com/

Astronomical Applications Department of the U.S. Naval Observatory

http://aa.usno.navy.mil/

Source of sunrise and sunset times

References

Smoot, Jeff. Climbing Washington’s Mountains. Guilford, Connecticut: The Globe Pequot Press, 2002. Pgs. 24-29.

Nelson, Jim; Potterfield, Peter. Selected Climbs in the Cascades, Volume I. 2nd ed. Seattle: The Mountaineers Books, 1993. 2nd ed. 2003. Pgs. 278-282.

Green Trails Maps. Mount Baker Wilderness Climbing, Map No. 13S. 1:24,000. Seattle, WA: www.greentrailsmaps.com, 2012.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. BAKER PASS, WA. Baker Pass Quadrangle, Washington, 7.5-Minute Series (Topographic), 1:24,000. USDA Forest Service, March 29, 2012.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. MOUNT BAKER, WA. Mount Baker Quadrangle, Washington, 7.5-Minute Series (Topographic), 1:24,000. USDA Forest Service, March 29, 2012.