-

35471 Hits

35471 Hits

-

91.45% Score

91.45% Score

-

35 Votes

35 Votes

|

|

Area/Range |

|---|---|

|

|

61.43540°N / 143.25591°W |

|

|

Hiking, Mountaineering, Ice Climbing, Scrambling, Canyoneering, Skiing |

|

|

Spring, Summer, Fall |

|

|

16390 ft / 4996 m |

|

|

Overview

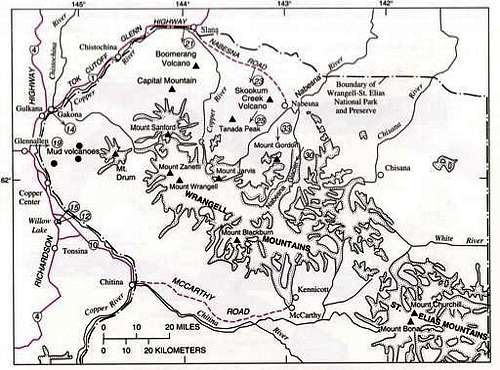

In times of fair weather, one can gaze east from the Glenn, Edgerton and Richardson Highways between Chitina and Slana and spy the towering peaks of Wrangell. Dominated by four glacier-clad volcanoes: Mount Sanford (16,237'), Mt. Drum (12,010'), Mount Wrangell (14,163') and Mount Blackburn (16,390'), the range dwarfs the landscape at its base. This extensive volcanic field forms part of the backbone of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, which at 20,587 mi² (53,321 km²), is the largest protected wilderness in the United States. The park is larger than the entire nation of Switzerland.The Wrangell lie almost wholly within the United States, just northwest of the St. Elias Mountains. Chitistone Canyon divides these two mighty ranges, carved by the glacial runoff that converges to form the Copper River.

Highest Peaks

| Peak | Elevation (feet) | Elevation (meters) |

| Mount Blackburn | 16,390 | 4,996 |

| Mount Sanford | 16,237 | 4,949 |

| Mount Wood | 15,879 | 4,842 |

| Mount Wrangell | 14,163 | 4,317 |

| Regal Mountain | 13,845 | 4,220 |

| Mount Jarvis | 13,421 | 4,091 |

| Mount Zanetti | 13,009 | 3,965 |

Geology

Named for the Russian explorer Baron von Wrangel, the Wrangell Mountains are a volcanic chain made up of thousands of lava flows. This extensive volcanic terrain, which is called the Wrangell volcanic field, covers about 4,000 square miles (10,400 km2) and extends eastward from the Copper River Basin into the St. Elias Mountains and Yukon Territory.The basement rocks on which the Wrangell volcanoes erupted are much older and have a complex geologic history. They were not formed where they are found today, but were transported a great distance. These rocks, known as the Wrangellia composite terrane, were formed at a considerably lower, warmer latitude, thousands of miles south of their present position some 300 million years ago. Many of the mountain ranges of interior Alaska are the result of the collision of smaller, moving tectonic plates with the North American continent. Eventually, they will all sink back into the mantle after millions of years. There the matierial will form new mountains and repeat the process.

The forces capable of moving terranes and even continents are the result of motion and interaction between many semi-rigid plates in the Earth's crust. The speeds at which these crustal plates move across the surface of the Earth range from <1 to 5 inches per year. Over the eons, crustal plates move hundreds or even thousands of miles. The driving force: massive upwelling of magma along rift zones. Most of these rift zones occur in the Earth's mid-ocean areas, where they mark the boundaries between oceanic crustal plates. As new magma is erupted along an oceanic rift, it forces older crusts outward. Old crusts may be consumed through subduction, where one plate (usually the heavier) plunges under a continental plate in a process called subduction. The subducted plate melts again and rising magma streams up from the slab to eventually erupt at the surface as a lava flow, dome or volcanic ash.

How large is the Wrangell Volcanic Ridge?

The Wrangell volcanoes are among the highest mountains in North America and some of the largest by volume in the world. They range in elevation from only a few thousand feet above sea level (Mount Boomerang, 3,949') to the summit of Blackburn at neary 16,400'.

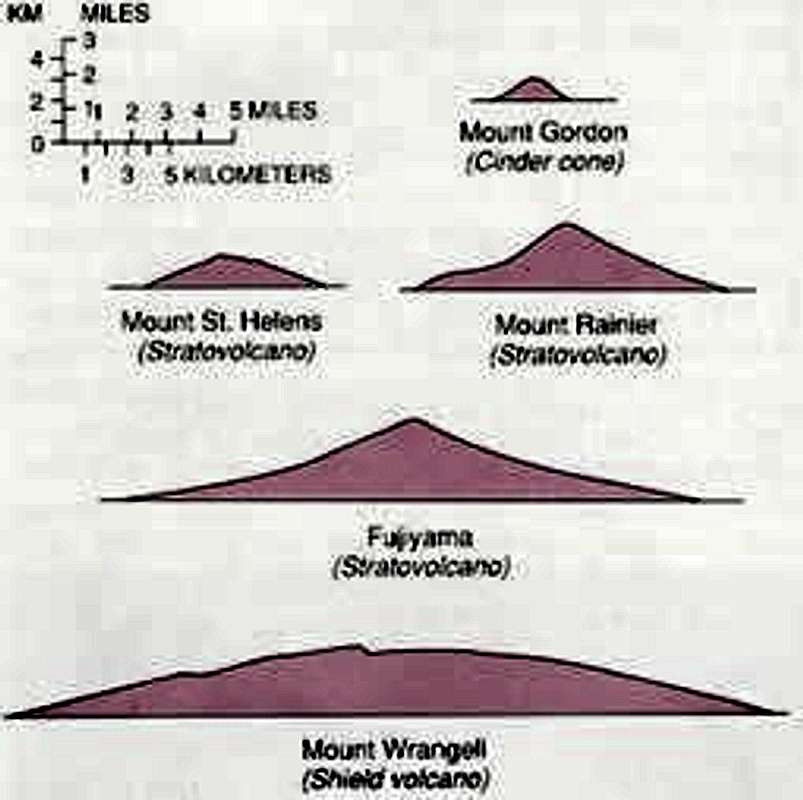

In comparison to most strato-volcanoes, such as those along the Pacific Rim of Fire, the Wrangell shield volcanoes are far more voluminous. Mt. Wrangell and Mt. Sanford each consist of 250 cubic miles of lava. Compare that to about 8 cubic miles for Mt. St. Helens, 47 cubic miles for Mt. Rainier or 184 cubic miles for Mt. Fuji.

Most Recent Eruptions

Mt. Wrangell erupted in 1784, 1884-5, and 1900. On clear, cold, and calm days, steam plumes are often visible. Large volumes of ash were deposited 1200 and 1900 years ago from the eruption of nearby Mt. Churchill.

Getting There

Access into the Park/Preserve is usually by private vehicle along unpaved gravel roads, via watercraft, or by chartered air taxi service from Tok, Glennallen (Gulkana), McCarthy, Valdez, Cordova or Yakutat. With the exception of Yakutat and Cordova, these communities can be reached by private vehicle or bus lines from Anchorage. Yakutat and Cordova can be reached by Alaska Airlines (800)-426-0333 which offers daily jet service from both Juneau and Anchorage. Cordova and Valdez are accessed via the Alaska Marine Highway (State Ferry) (800) 642-0066.Reaching Glennallen by Bus or Van

Glennallen, the largest community near the park, is located at the junction of the Richardson and Glenn Highways.

Alaska Direct Bus Line (800) 770-6652 runs a bus from Anchorage to Tok, with multiple stops along the way, including in Glennallen. Call for days and schedules.

Seasonally, Backcountry Connections (907) 822-5292 makes daily runs from Glennallen to McCarthy.

Seasonally, McCarthy-Kennicott Shuttle (907) 554-1222 provides transportation from Anchorage all the way to McCarthy. Shuttles depart Anchorage on Wednesdays and Sundays at 9:00 am and arrive at McCarthy by 5:00 pm.

Reaching Glennallen or McCarthy by Air

Ellis Air has scheduled flights on Wednesdays and Fridays. Call (907)822-3368 or 800-478-3368 for prices and flight times. Wrangell Mountain Air, (800) 478-1160, offers twice daily service (Mid-May to Mid-September) from Chitina to McCarthy with advance reservations.

Entering the park from Glennallen

From Glennallen, surface access into the Park/Preserve is via either the McCarthy Road (from Chitina to McCarthy - 60 miles) or the Nabesna Road (from Slana to Nabesna - 42 miles). Both are unpaved gravel roads usually suitable for passenger vehicles. Drivers should check current road conditions at Park Headquarters, (907) 822-5234, or at the respective ranger station listed below:

McCARTHY ROAD: Chitina Ranger Station (summer only) (907) 823-2205

NABESNA ROAD: Nabesna Ranger Station, (907) 822-5238

PARK HEADQUARTERS:Wrangell-St. Elias Park and Preserve Mile 106.8 Richardson Hwy. P.O. Box 439 Copper Center, AK 99573 (907) 822-5234.

In summer, most visitors approach the Wrangell via the unpaved road between Chitina and McCarthy. Backcountry hikers can choose to either turn off at the road leading to Nugget Creek Trail or the Dixie Pass Trail a mile past the Nugget Creek turnoff. In winter, air taxi is the only way in and out of the wilderness.

If taking Nabesna Road, please note: once you pass the small airport in Nabesna there is a parking lot. Past that parking lot the road is not maintained and is not recommended for anyone who doesn't have high clearance and four wheel drive, or anyone who cares about their vehicle paint being scratched up by brush on both sides. At the end, four miles further, is Nabesna mine.

It is recommended that all climbers fill out a "Trip Itinerary" and leave it at park headquarters, or one of the ranger stations in Slana, Gulkana, Chitina or Yakutat.

All climbing expeditions that leave Alaska to enter Kluane National Park, Canada must secure a permit in advance from the:

Superintendent

Kluane National Park

Phone: 403-634-2251

The river rises out of the Copper Glacier, which lies on the northeast side of Mount Wrangell. It flows almost due north along the east side of Mount Sanford, where it turns west, forming the northwest edge of the Wrangell Mountains and separating them from the rugged Mentasta Mountains to the northeast. It continues to turn, first heading southwest, and then southeast through a broad expanse of wetlands to Chitina. There it is joined by the Chitina River. Further downstream it flows southwest, carving its way through a narrow glacier-lined gap in the Chugach Mountains. From here it plunges into the frigid Gulf of Alaska.

The river's name comes for the abundant copper deposits along the upper reaches of the river. These deposits were exploited by Alaska Natives and later by frontiersmen from the Russian Empire and the United States. Copper extraction was difficult, as the Copper is scarcely navigable at its mouth, due to large amounts of sediment. The construction of the Copper River and Northwestern Railway from Cordova through the upper river valley in 1908-1911 improved access to the mineral resources. The famed Kennecott Mine delved into an abundant deposit discovered in 1898. The mine, abandoned in 1938, is now a ghost town and tourist site. The Tok Cut-Off, part of the Alaskan Highway, follows the Copper River Valley to the north of the Chugach Mountains.

The Copper is famed for its salmon runs. Over 2 million salmon enter the river each year for spawning. The Copper River Delta, which extends for 700,000 acres (2,800 km²), is the considered the largest contiguous wetlands on the Pacific coast of North America. The wetlands are visited by 16 million shorebirds each year, including the world's entire population of western sandpipers. It is also home to earth's largest population of nesting trumpeter swans and is the sole nesting site for the dusky Canada goose.

The Million Dollar Bridge, which crosses the river, was originally built to connect the seaside town of Cordova to the rest of Alaska. That plan was abandoned during the 1964 earthquake which destroyed a portion of the bridge. That portion has now been fixed.

Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve does not allow cabin reservations, however there are 5 shelter cabins open to public and park use. All cabins are available on a first-come first-served basis. The 5 cabins are: Nugget Creek, Jake's Bar on the Chitina River, Too Much Johnson Cabin in Chisana, and Hubert's Landing near the Chitina Glacier. Do not expect amenities or furnishings of any kind. Please leave cabins clean and ready for emergency use. Please restock firewood for the next user.

Other cabins, lodging, or structures shown on USGS maps may be used to locate oneself in an emergency. Some are privately owned, so please check at the park ranger station before your trip. Many cabins are in complete disrepair. As such, they may not provide adequate shelter in inclement weather. Some of the structures were built in the early part of the 20th century and are valued historic resources. If you need to seek shelter in these cabins during an emergency, please be very careful not to inflict further damage on them.

Insect repellent and head nets are highly recommended during the summer season.

Extra food and clothing, a signal mirror, smoke flare, durable space blankets, plastic bags, and a good first aid kit are extremely valuable if you plan on being out for several days.Cord can be used to make a shelter and hang food in trees. The author recommends water purification filters or chemicals. Some hikers even carry pocket strobe lights, and a few carry personal locator beacons.

Plan to be self sufficient in any emergency. The land is vast and remote, and you cannot count on early help if you have difficulties. Try and keep your gear lightweight and durable, ready to withstand rigorous use. Help could be many hours away should something go wrong with your gear.

Bring your food, equipment and other supplies with you. Avoid food such as bacon or smoked fish, soaps, and cosmetics with strong odors as they attract bears. Bottles and cans are hard to dispose of. If you take them in, you are expected to carry them out. Without some sort of bear proof storage, you should be prepared to hang your food as high as possible. Federal Aviation Administration regulations prohibit carrying fuel in containers such as stoves on commercial airlines.

A gasoline stove is essential. Wood is scarce and often wet.

Boots should be a sturdy hiking or mountaineering type that provides good ankle support. Some hikers prefer boots with the rubber shoe and leather upper, like the Maine Hunting Shoe. You can count on your feet getting wet regardless of your boot type, so durability and support should be a prime concern. Many pair of socks are essential.

You can purchase maps of the area at the U.S. Geological Survey, 1-800-USA-MAPS. The Yakutat District Ranger also sells USGS maps.

The following maps cover the Malaspina Forelands, Yakutat area and Dry Bay at 1:250,000 scale:

Yakutat

Mt. St. Elias

Bering Glacier

Icy Bay

Mt. Fairweather

Skagway

Durable rain/snow gear that covers both the upper and lower torso is a must for hikes of any length. Gear should keep out water in a steady down pour. If you spend any length of time in the Wrangell, you will eventually get wet in a significant storm, unless extremely lucky. Wool or synthetic clothing that insulates when wet is key. The weather in the Wrangell Mountains can change without warning. Hypothermia is always a possibility for the unprepared novice.

You should have a tent with a waterproof floor, rain-fly, and a no-see-um netting. Your tent should be designed to withstand strong winds. Bring plenty of extra stakes and strong cord to keep the tent secure. Synthetics like ‘Polarguard' or ‘Fiberfill' are better than down in the wet environment of the Wrangells because synthetics will insulate when wet while many downs will not. A sleeping pad always provides insulation as well as comfort.

The staff at Wrangell-St. Elias National Park urge you to stop by, write to or call the Headquarter office or visitor center for help in the final planning of your trip into the Wrangells. All peaks in the range require crampons, ropes and an ice axe year-round.

There are no maintained backcountry trails. The best hiking routes are along river bars, lake shores, and gravel ridges. Even on the best routes, you must occasionally cross rivers or fight through dense brush or marshy flats. Routes often selected are wildlife trails. Stay alert for bears and moose as you travel as wildlife also seeks the easiest routes through brush and forest. Stay away from low lying tundra flats because tussocks and marshy ground predominates there, making hiking extremely difficult. The mosquito is king in this environment. Alder thickets on hillsides, and willow patches along the water courses are often impenetrable. They may also hide bears. Be sure to make noise.

Most backcountry routes in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve require numerous creek or river crossings. Man-made crossings are virtually nonexistent and you must be familiar with safe techniques for crossing rivers and streams. Many are impassable, even for experts. Others can change quickly from bubbling streams to raging torrents.

Water volume, turbidity and velocity vary drastically by season, time of day and upstream weather conditions. On warm days melting snow and glacial ice swell streams that were easily crossed in the morning to flood stage by mid-afternoon. In glaciated areas, hotter, sunny days cause higher volume in the streams due to the ice melt. Voluminous, warm rain is also a contributing factor.

Keep these points in mind when crossing water channels:

Choose the safest TIME to cross.

Cross early in the day whenever possible.

Be aware of storms in the area; cross before storms whenever possible.

Choose the safest PLACE to cross

The widest or most braided portion of the channel is usually the most shallow. Straight channels usually exhibit uniform flow while bends often reveal deep cut banks and swift Water on the outside edge.

Water has less momentum on level ground than when flowing down an incline.

Cross with care using trekking poles or a partner for stability.

A Tidebook is an especially important item if boating, kayaking, fishing or hiking the coast. Remember, camp above the hightide line, always secure your boat or kayak when on shore and access the outwash streams and river channels at high slack water. If you cross a stream or walk the beach at low tide remember that conditions may be drastically different should you return by the same route a couple hours later. The tide changes from high to low every six hours and the water is very cold (34° F).

1. Plan Ahead and Prepare

Carefully designing your trip to match your expectations and outdoor skill level is the first step in being prepared. Adequate trip planning and preparation helps to accomplish trip goals safely, while minimizing impacts on the environment and on other users.

Know the area and what to expect, including regulations and special concerns of the area.

Travel in small groups, during seasons or days of a week when use levels are low.

Bears may be present; balance safety concerns in bear country with ecological and social impact concerns.

Select appropriate equipment to help you Leave No Trace.

Repackage food into reusable containers, creating less trash to pack out.

2. Camp and Travel on Durable Surfaces

Whenever you travel and camp, confine your use to surfaces that are resistant to impact.

In popular areas, concentrate use. In remote areas, spread use.

Hike on existing trails to minimize disturbance to wildlife, soil and vegetation.

Choose an established campsite, one with a slight slope so rain water can drain.

Store food so that it is unavailable and uninviting to bears and small animals.

Before departing, make sure your camp is as clean or cleaner than when you arrived.

3. Pack it In, Pack it Out

Trash and garbage have no place in the backcountry.

Consider "Leave No Trace" a challenge to take out everything that you brought into the backcountry.

Pack out all of your liter.

Repackage food into reusable containers and remove any excess packaging.

Dispose of trash and garbage properly.

Store food and odorous items in bear resistant food containers or hang items 10 feet above the ground.

4. Properly Dispose of What You Can't Pack Out.

As visitors to the backcountry, we create certain kinds of waste which cannot be packed out.

These include human waste, waste water from cooking and washing.

Dispose of human waste responsibility, utilize pit toilets or dig a cat hole 200 feet from the water.

Use toilet paper sparingly, pack it out in doubled plastic bags to confine odor.

Minimize soap and food residues in waste water.

Avoid contaminating water sources when washing, maintain 200 feet from a water source.

5. Leave What You Find.

The Wilderness Act states that wilderness "... is recognized as an area... where man himself is a visitor who does not remain,...with the imprint of man's work substantially unnoticeable..." People come to the wildlands to enjoy them in their natural state. Allow others a sense of discovery by leaving rocks, plants, archaeological artifacts antlers, and other objects as you find them.

Minimize site alteration when camping, do not build structures.

Avoid damaging live trees and plants.

Avoid disturbing wildlife.

Leave natural objects and cultural artifacts for others to enjoy.

It is illegal to remove any cultural objects from Wrangell - St Elias National Park and Preserve.

Cultural artifacts are protected by the Archaeological Resources Protection Act. All these "pieces of the past" contribute to our understanding of human and natural history, including the effects of disease, climate changes, and shifting animal populations on the land and her people. Removing these artifacts takes them out of context and removes a chapter from an important story. If you discover an artifact, enjoy it where it is. Leave it as you found it.

6. Minimize Use and Impact from Fires

The use of campfires in the backcountry, once a necessity, is now steeped in history and tradition. Stoves are now essential equipment for minimum-impact camping trips because they are fast and eliminate firewood availability as a concern in campsite selection.

Use dead and down wood only.

In high use areas, build campfires in existing fire rings to concentrate impacts.

These principles and practices depend more on attitude and awareness than on rules and regulations; they must be based on a respect for and appreciation of wild places and their inhabitants.

An Alaska fishing license is required and all state rules apply. Release or cut your line when a bear approaches.

Salmon provide food for bears, bald eagles, gulls and other creatures that forage the stream during the annual run. They have also been important to Wrangell - St Elias people for several thousand years.

Fish are one of Alaska's greatest renewable resources. By practicing proper catch and release fishing, today's anglers preserve quality fishing for the anglers of tomorrow. Use artificial flies and lures to catch fish that you plan to release. Use barbless hooks and an appropriate hook size. Pliers can be used to pinch down barbs on conventional hooks.

Avoid surprising animals at close range. Whistle, talk, sing, or otherwise make noise when hiking in areas where visibility is limited or bear sign present. Take no pets; they are prohibited in the backcountry. A dog's valor may turn into retreat bringing an infuriated bear to you.

Be alert to sign (droppings, diggings, fresh tracks, etc.), sounds, or other indications of bears. Be particularly wary when hiking wildlife trails, salmon streams, or other areas where bears concentrate.

Food and beverages should never be left unattended. Foodstuffs with strong odors such as fish, cheese, sausage, and fresh meats should be stored in a food cache, a bear resistant container, or suspended 10 feet above ground. Carry all refuse and garbage out! Buried refuse will attract bears.

Keep packs and other personal gear on your person. It is easy to become separated from belongings left lying on the ground when a bear unexpectedly approaches. Bears will investigate, often destructively.

Bears approach anglers because they have learned to recognize them as a source of food. Stop fishing when bears are present.

If you keep a fish, you should remove the fish immediately to a proper food storage area.

Do not approach bears

The minimum safe distance from any bear is 50 yards; from a sow with young it is 100 yards. These are MINIMUM distances, there are many times that greater distances are required!

Regardless of precautions taken, you may come across a bear. Usually they will run away. A bear standing on hind legs may only be trying to sense you better, not preparing to attack. Even a charge is often a bluff, ending abruptly short of physical contact.

If you see a bear at a distance, turn around or make a wide detour. Keep upwind if possible so the bear will get your scent and know you're there. Talk in an assured tone to communicate your presence. Treat animals as if cubs are nearby. Assume the bear will be defensive. Do not approach closer to scare a bear away as you may be considered a threat.

Avoid actions that interfere with bear movement or foraging activities.

Be satisfied with a distant photograph, or use a telephoto lense. Many fatalities and injuries have been related to photography.

Do not corner an animal. Allow them plenty of space and an escape route.

Bears are typically solitary animals. Much of their communication at feeding aggregations, such as occur on Brooks River, serves to maintain spacing and avoid conflict. Bears appear to have only a limited repertoire for this purpose. These behavior patterns are not highly ritualized, as in some species; therefore, their meaning is largely dependent on the context of the situation.

Descriptions of some behavior and a general interpretation of meaning follow to help you understand what a bear may be trying to tell you. Remember, each bear is an individual and each encounter is unique.

Postures

Standing on hind legs - A bear standing bipedally is typically not expressing aggression. Bears generally stand on their hind legs to gain more information, both olfactory and visual.

Stationary lateral body orientation - A bear may stand broadside to assert itself in some instances. In encounters with human, it has usually been interpreted as a demonstration of size.

Stationary frontal orientation - If a bear is standing and facing you, it is certainly not being submissive. This is an aggressive position and may signal a charge. It is likely waiting for you to withdraw.

Vocalizations

Huffing - When a bear is tense, it may forcibly exhale a series of several sharp, rasping huffs. A mother may also huff in order to gain the attention of her young.

Woof - A startled bear may emit a single sharp exhale that lakes the harsh quality of a huff. If her cubs woof, a mother will immediately become alert to the situation.

Jaw-Popping - Females with young often emit a throaty popping sound, apparently to beckon their cubs when danger is sensed. A mother vocalizing in this manner should be considered nervous and extremely stressed. Bears other than sows also jaw-pop.

Growl, snarl, roar - Clear indication of intolerance.

Other Indicators

Yawning - Indicates tension. This behavior may results from the close proximity of another bear or human presence.

Excessive Salivation - A clear sign of tension, salivation may appear as white foam around the bear's mouth.

The Charge

The vast majority of charges are ones in which the bear stops before making contact. The intensity of the charge or associated vocalizations may vary, but it is distinct in that it is an aggressive or defensive act clearly directed at another bear or human. Bears may charge immediately, as a sow fearing for her cubs, or may emit stressed or erratic behavior before charging.

There is no guaranteed lifesaving method of reacting to an aggressive bear. Some behavior patterns have proven more successful in close encounters than others. Take a calm assured posture. A firm voice and gradual departure are better than a retreat in panic. Include the nature of your surroundings in your reaction.

As a last resort, lie face down, protect your neck with your hands and arms, and don't move. This requires considerable courage, but resistance would be futile. Numerous incidents exist where a bear has sniffed and departed without serious injury.

This information was provided by the National Park Service.

Mc Carthy Current Conditions & Forecast

St. Elias Alpine Guides LLC

[img:56472:alignleft:small:][img:56509:alignright:small:]

Permit Information

It is recommended that all climbers fill out a "Trip Itinerary" and leave it at park headquarters, or one of the ranger stations in Slana, Gulkana, Chitina or Yakutat.

All climbing expeditions that leave Alaska to enter Kluane National Park, Canada must secure a permit in advance from the:

Superintendent

Kluane National Park

Phone: 403-634-2251

The Copper River

The Wrangell Mountains are the source of numerous rivers, including the Copper or Atna. Some 300 mi (480 km) long, the Copper drains into the Gulf of Alaska and is known for its vast delta ecosystem, as well as its runs of wild salmon, which are among the most highly prized stocks on earth. The brief Copper River salmon season runs from mid-May to mid-June.The river rises out of the Copper Glacier, which lies on the northeast side of Mount Wrangell. It flows almost due north along the east side of Mount Sanford, where it turns west, forming the northwest edge of the Wrangell Mountains and separating them from the rugged Mentasta Mountains to the northeast. It continues to turn, first heading southwest, and then southeast through a broad expanse of wetlands to Chitina. There it is joined by the Chitina River. Further downstream it flows southwest, carving its way through a narrow glacier-lined gap in the Chugach Mountains. From here it plunges into the frigid Gulf of Alaska.

The river's name comes for the abundant copper deposits along the upper reaches of the river. These deposits were exploited by Alaska Natives and later by frontiersmen from the Russian Empire and the United States. Copper extraction was difficult, as the Copper is scarcely navigable at its mouth, due to large amounts of sediment. The construction of the Copper River and Northwestern Railway from Cordova through the upper river valley in 1908-1911 improved access to the mineral resources. The famed Kennecott Mine delved into an abundant deposit discovered in 1898. The mine, abandoned in 1938, is now a ghost town and tourist site. The Tok Cut-Off, part of the Alaskan Highway, follows the Copper River Valley to the north of the Chugach Mountains.

The Copper is famed for its salmon runs. Over 2 million salmon enter the river each year for spawning. The Copper River Delta, which extends for 700,000 acres (2,800 km²), is the considered the largest contiguous wetlands on the Pacific coast of North America. The wetlands are visited by 16 million shorebirds each year, including the world's entire population of western sandpipers. It is also home to earth's largest population of nesting trumpeter swans and is the sole nesting site for the dusky Canada goose.

The Million Dollar Bridge, which crosses the river, was originally built to connect the seaside town of Cordova to the rest of Alaska. That plan was abandoned during the 1964 earthquake which destroyed a portion of the bridge. That portion has now been fixed.

Camping

There are no federal camping facilities in the park. No permits are required to access the Wrangell Mountains. The BLM and the State of Alaska maintain camping facilities along Richardson Highway, Tok Cutoff and Edgerton Highway. You may camp anywhere in the park, but be aware that there are extensize tracks of private land, particularly along the Nabesna and McCarthy road corridors.Public Lodging

Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve does not allow cabin reservations, however there are 5 shelter cabins open to public and park use. All cabins are available on a first-come first-served basis. The 5 cabins are: Nugget Creek, Jake's Bar on the Chitina River, Too Much Johnson Cabin in Chisana, and Hubert's Landing near the Chitina Glacier. Do not expect amenities or furnishings of any kind. Please leave cabins clean and ready for emergency use. Please restock firewood for the next user.

Other cabins, lodging, or structures shown on USGS maps may be used to locate oneself in an emergency. Some are privately owned, so please check at the park ranger station before your trip. Many cabins are in complete disrepair. As such, they may not provide adequate shelter in inclement weather. Some of the structures were built in the early part of the 20th century and are valued historic resources. If you need to seek shelter in these cabins during an emergency, please be very careful not to inflict further damage on them.

Gear

Waterproof matches in airtight containers, metal matches, fire starter and ‘tinder' are suggested.Insect repellent and head nets are highly recommended during the summer season.

Extra food and clothing, a signal mirror, smoke flare, durable space blankets, plastic bags, and a good first aid kit are extremely valuable if you plan on being out for several days.Cord can be used to make a shelter and hang food in trees. The author recommends water purification filters or chemicals. Some hikers even carry pocket strobe lights, and a few carry personal locator beacons.

Plan to be self sufficient in any emergency. The land is vast and remote, and you cannot count on early help if you have difficulties. Try and keep your gear lightweight and durable, ready to withstand rigorous use. Help could be many hours away should something go wrong with your gear.

Food and Supplies

Bring your food, equipment and other supplies with you. Avoid food such as bacon or smoked fish, soaps, and cosmetics with strong odors as they attract bears. Bottles and cans are hard to dispose of. If you take them in, you are expected to carry them out. Without some sort of bear proof storage, you should be prepared to hang your food as high as possible. Federal Aviation Administration regulations prohibit carrying fuel in containers such as stoves on commercial airlines.

A gasoline stove is essential. Wood is scarce and often wet.

Footwear

Boots should be a sturdy hiking or mountaineering type that provides good ankle support. Some hikers prefer boots with the rubber shoe and leather upper, like the Maine Hunting Shoe. You can count on your feet getting wet regardless of your boot type, so durability and support should be a prime concern. Many pair of socks are essential.

Maps

You can purchase maps of the area at the U.S. Geological Survey, 1-800-USA-MAPS. The Yakutat District Ranger also sells USGS maps.

The following maps cover the Malaspina Forelands, Yakutat area and Dry Bay at 1:250,000 scale:

Yakutat

Mt. St. Elias

Bering Glacier

Icy Bay

Mt. Fairweather

Skagway

Rain Gear and Clothing

Durable rain/snow gear that covers both the upper and lower torso is a must for hikes of any length. Gear should keep out water in a steady down pour. If you spend any length of time in the Wrangell, you will eventually get wet in a significant storm, unless extremely lucky. Wool or synthetic clothing that insulates when wet is key. The weather in the Wrangell Mountains can change without warning. Hypothermia is always a possibility for the unprepared novice.

Tents and Seeping Bags

You should have a tent with a waterproof floor, rain-fly, and a no-see-um netting. Your tent should be designed to withstand strong winds. Bring plenty of extra stakes and strong cord to keep the tent secure. Synthetics like ‘Polarguard' or ‘Fiberfill' are better than down in the wet environment of the Wrangells because synthetics will insulate when wet while many downs will not. A sleeping pad always provides insulation as well as comfort.

Backcountry Travel

The staff at Wrangell-St. Elias National Park urge you to stop by, write to or call the Headquarter office or visitor center for help in the final planning of your trip into the Wrangells. All peaks in the range require crampons, ropes and an ice axe year-round.

There are no maintained backcountry trails. The best hiking routes are along river bars, lake shores, and gravel ridges. Even on the best routes, you must occasionally cross rivers or fight through dense brush or marshy flats. Routes often selected are wildlife trails. Stay alert for bears and moose as you travel as wildlife also seeks the easiest routes through brush and forest. Stay away from low lying tundra flats because tussocks and marshy ground predominates there, making hiking extremely difficult. The mosquito is king in this environment. Alder thickets on hillsides, and willow patches along the water courses are often impenetrable. They may also hide bears. Be sure to make noise.

River Crossing

Most backcountry routes in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve require numerous creek or river crossings. Man-made crossings are virtually nonexistent and you must be familiar with safe techniques for crossing rivers and streams. Many are impassable, even for experts. Others can change quickly from bubbling streams to raging torrents.

Water volume, turbidity and velocity vary drastically by season, time of day and upstream weather conditions. On warm days melting snow and glacial ice swell streams that were easily crossed in the morning to flood stage by mid-afternoon. In glaciated areas, hotter, sunny days cause higher volume in the streams due to the ice melt. Voluminous, warm rain is also a contributing factor.

Keep these points in mind when crossing water channels:

Choose the safest TIME to cross.

Cross early in the day whenever possible.

Be aware of storms in the area; cross before storms whenever possible.

Choose the safest PLACE to cross

The widest or most braided portion of the channel is usually the most shallow. Straight channels usually exhibit uniform flow while bends often reveal deep cut banks and swift Water on the outside edge.

Water has less momentum on level ground than when flowing down an incline.

Cross with care using trekking poles or a partner for stability.

Tidebook

A Tidebook is an especially important item if boating, kayaking, fishing or hiking the coast. Remember, camp above the hightide line, always secure your boat or kayak when on shore and access the outwash streams and river channels at high slack water. If you cross a stream or walk the beach at low tide remember that conditions may be drastically different should you return by the same route a couple hours later. The tide changes from high to low every six hours and the water is very cold (34° F).

The Six Principles of Leave No Trace

1. Plan Ahead and Prepare

Carefully designing your trip to match your expectations and outdoor skill level is the first step in being prepared. Adequate trip planning and preparation helps to accomplish trip goals safely, while minimizing impacts on the environment and on other users.

Know the area and what to expect, including regulations and special concerns of the area.

Travel in small groups, during seasons or days of a week when use levels are low.

Bears may be present; balance safety concerns in bear country with ecological and social impact concerns.

Select appropriate equipment to help you Leave No Trace.

Repackage food into reusable containers, creating less trash to pack out.

2. Camp and Travel on Durable Surfaces

Whenever you travel and camp, confine your use to surfaces that are resistant to impact.

In popular areas, concentrate use. In remote areas, spread use.

Hike on existing trails to minimize disturbance to wildlife, soil and vegetation.

Choose an established campsite, one with a slight slope so rain water can drain.

Store food so that it is unavailable and uninviting to bears and small animals.

Before departing, make sure your camp is as clean or cleaner than when you arrived.

3. Pack it In, Pack it Out

Trash and garbage have no place in the backcountry.

Consider "Leave No Trace" a challenge to take out everything that you brought into the backcountry.

Pack out all of your liter.

Repackage food into reusable containers and remove any excess packaging.

Dispose of trash and garbage properly.

Store food and odorous items in bear resistant food containers or hang items 10 feet above the ground.

4. Properly Dispose of What You Can't Pack Out.

As visitors to the backcountry, we create certain kinds of waste which cannot be packed out.

These include human waste, waste water from cooking and washing.

Dispose of human waste responsibility, utilize pit toilets or dig a cat hole 200 feet from the water.

Use toilet paper sparingly, pack it out in doubled plastic bags to confine odor.

Minimize soap and food residues in waste water.

Avoid contaminating water sources when washing, maintain 200 feet from a water source.

5. Leave What You Find.

The Wilderness Act states that wilderness "... is recognized as an area... where man himself is a visitor who does not remain,...with the imprint of man's work substantially unnoticeable..." People come to the wildlands to enjoy them in their natural state. Allow others a sense of discovery by leaving rocks, plants, archaeological artifacts antlers, and other objects as you find them.

Minimize site alteration when camping, do not build structures.

Avoid damaging live trees and plants.

Avoid disturbing wildlife.

Leave natural objects and cultural artifacts for others to enjoy.

It is illegal to remove any cultural objects from Wrangell - St Elias National Park and Preserve.

Cultural artifacts are protected by the Archaeological Resources Protection Act. All these "pieces of the past" contribute to our understanding of human and natural history, including the effects of disease, climate changes, and shifting animal populations on the land and her people. Removing these artifacts takes them out of context and removes a chapter from an important story. If you discover an artifact, enjoy it where it is. Leave it as you found it.

6. Minimize Use and Impact from Fires

The use of campfires in the backcountry, once a necessity, is now steeped in history and tradition. Stoves are now essential equipment for minimum-impact camping trips because they are fast and eliminate firewood availability as a concern in campsite selection.

Use dead and down wood only.

In high use areas, build campfires in existing fire rings to concentrate impacts.

These principles and practices depend more on attitude and awareness than on rules and regulations; they must be based on a respect for and appreciation of wild places and their inhabitants.

Fishing

An Alaska fishing license is required and all state rules apply. Release or cut your line when a bear approaches.

Salmon provide food for bears, bald eagles, gulls and other creatures that forage the stream during the annual run. They have also been important to Wrangell - St Elias people for several thousand years.

Fish are one of Alaska's greatest renewable resources. By practicing proper catch and release fishing, today's anglers preserve quality fishing for the anglers of tomorrow. Use artificial flies and lures to catch fish that you plan to release. Use barbless hooks and an appropriate hook size. Pliers can be used to pinch down barbs on conventional hooks.

Bears!

Avoid surprising animals at close range. Whistle, talk, sing, or otherwise make noise when hiking in areas where visibility is limited or bear sign present. Take no pets; they are prohibited in the backcountry. A dog's valor may turn into retreat bringing an infuriated bear to you.

Be alert to sign (droppings, diggings, fresh tracks, etc.), sounds, or other indications of bears. Be particularly wary when hiking wildlife trails, salmon streams, or other areas where bears concentrate.

Food and beverages should never be left unattended. Foodstuffs with strong odors such as fish, cheese, sausage, and fresh meats should be stored in a food cache, a bear resistant container, or suspended 10 feet above ground. Carry all refuse and garbage out! Buried refuse will attract bears.

Keep packs and other personal gear on your person. It is easy to become separated from belongings left lying on the ground when a bear unexpectedly approaches. Bears will investigate, often destructively.

Bears approach anglers because they have learned to recognize them as a source of food. Stop fishing when bears are present.

If you keep a fish, you should remove the fish immediately to a proper food storage area.

Do not approach bears

The minimum safe distance from any bear is 50 yards; from a sow with young it is 100 yards. These are MINIMUM distances, there are many times that greater distances are required!

Regardless of precautions taken, you may come across a bear. Usually they will run away. A bear standing on hind legs may only be trying to sense you better, not preparing to attack. Even a charge is often a bluff, ending abruptly short of physical contact.

If you see a bear at a distance, turn around or make a wide detour. Keep upwind if possible so the bear will get your scent and know you're there. Talk in an assured tone to communicate your presence. Treat animals as if cubs are nearby. Assume the bear will be defensive. Do not approach closer to scare a bear away as you may be considered a threat.

Avoid actions that interfere with bear movement or foraging activities.

Be satisfied with a distant photograph, or use a telephoto lense. Many fatalities and injuries have been related to photography.

Do not corner an animal. Allow them plenty of space and an escape route.

Bears are typically solitary animals. Much of their communication at feeding aggregations, such as occur on Brooks River, serves to maintain spacing and avoid conflict. Bears appear to have only a limited repertoire for this purpose. These behavior patterns are not highly ritualized, as in some species; therefore, their meaning is largely dependent on the context of the situation.

Descriptions of some behavior and a general interpretation of meaning follow to help you understand what a bear may be trying to tell you. Remember, each bear is an individual and each encounter is unique.

Postures

Standing on hind legs - A bear standing bipedally is typically not expressing aggression. Bears generally stand on their hind legs to gain more information, both olfactory and visual.

Stationary lateral body orientation - A bear may stand broadside to assert itself in some instances. In encounters with human, it has usually been interpreted as a demonstration of size.

Stationary frontal orientation - If a bear is standing and facing you, it is certainly not being submissive. This is an aggressive position and may signal a charge. It is likely waiting for you to withdraw.

Vocalizations

Huffing - When a bear is tense, it may forcibly exhale a series of several sharp, rasping huffs. A mother may also huff in order to gain the attention of her young.

Woof - A startled bear may emit a single sharp exhale that lakes the harsh quality of a huff. If her cubs woof, a mother will immediately become alert to the situation.

Jaw-Popping - Females with young often emit a throaty popping sound, apparently to beckon their cubs when danger is sensed. A mother vocalizing in this manner should be considered nervous and extremely stressed. Bears other than sows also jaw-pop.

Growl, snarl, roar - Clear indication of intolerance.

Other Indicators

Yawning - Indicates tension. This behavior may results from the close proximity of another bear or human presence.

Excessive Salivation - A clear sign of tension, salivation may appear as white foam around the bear's mouth.

The Charge

The vast majority of charges are ones in which the bear stops before making contact. The intensity of the charge or associated vocalizations may vary, but it is distinct in that it is an aggressive or defensive act clearly directed at another bear or human. Bears may charge immediately, as a sow fearing for her cubs, or may emit stressed or erratic behavior before charging.

There is no guaranteed lifesaving method of reacting to an aggressive bear. Some behavior patterns have proven more successful in close encounters than others. Take a calm assured posture. A firm voice and gradual departure are better than a retreat in panic. Include the nature of your surroundings in your reaction.

As a last resort, lie face down, protect your neck with your hands and arms, and don't move. This requires considerable courage, but resistance would be futile. Numerous incidents exist where a bear has sniffed and departed without serious injury.

This information was provided by the National Park Service.

Weather

The best time of year for climbing activity is April through June.

Mc Carthy Current Conditions & Forecast

External Links

Wrangell-Saint Elias National ParkSt. Elias Alpine Guides LLC

[img:56472:alignleft:small:][img:56509:alignright:small:]