-

80613 Hits

80613 Hits

-

96.82% Score

96.82% Score

-

69 Votes

69 Votes

|

|

Mountain/Rock |

|---|---|

|

|

37.83597°N / 107.95082°W |

|

|

Hiking, Mountaineering, Trad Climbing |

|

|

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter |

|

|

13113 ft / 3997 m |

|

|

Introduction

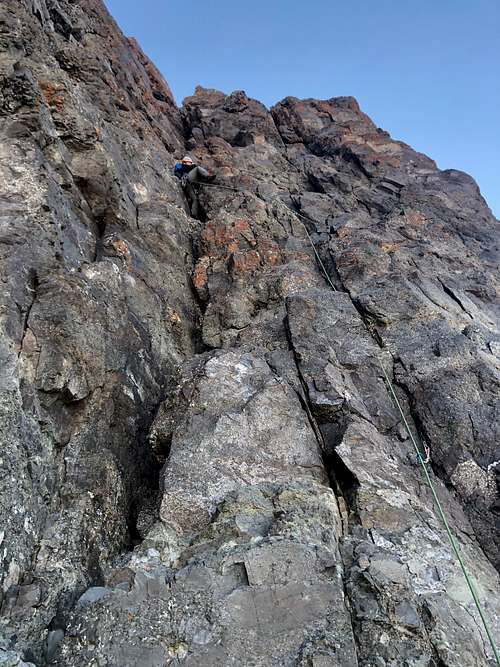

Lizard Head is a lofty volcanic pinnacle lying in the fabled San Juan Mountains of southwestern Colorado. It has a number of accolades: it is a 13,000+' volcanic pinnacle (how many of those can you think of?!); it's surrounded by numerous 14,000 ft. peaks; it is in one of the most beautiful regions of the Colorado Rockies; there is no non-technical way to its summit; and it has a storied climbing history. While many know of Lizard Head's existence, to reach its exclusive summit is an honor only earned by a select few. The easiest way up the formation is a 5.8 traditional rock climbing route, and the rock is far from perfect (or even reasonably good, for that matter). Its first ascent was achieved by Albert Ellingwood, quite possibly North America's greatest climber of his time, and was one of the most difficult ascents in the Americas at the time. Modern climbers with nylon ropes, sticky rubber, a good understanding of time-honored crack climbing techniques, and spring-loaded camming devices will have a difficult time imagining ascending the spire without any of these, as Ellingwood did (!!). If you find yourself at the top of this pinnacle at some point in your life, count yourself fortunate for joining a relatively small group, not to mention being in a very special, unique, and beautiful little part of the world.

History of the climb

Lizard Head has an intriguing climbing history. At the time of its first ascent in 1920 by Albert Ellingwood and Barton Hoag, Lizard Head was probably the hardest rock climb then completed in the United States.Overview

Lizard Head has been known as Colorado's hardest summit to reach as the easiest route is 5.8+. It stands out as a big pinnacle shooting into the sky. It almost looks like a desert tower except that it's at over 13,000 feet and the rock isn't great. The top 500 feet of Lizard Head is a near-vertical pillar. Heavy erosion leaving what's left of an ancient volcano. That being said, the rock is not Yosemite like. Many that have done it, never return again due to that factor. I would do it again though! It ain't that loose, nor as storied. The summit is the best in Colorado in my opinion. Lizard Head also has a bit of history.There are at least 3 routes in its south face. The standard route is what everyone uses though and the other routes, expect massive amounts of choss. There is potential for new routes if that's your sort of thing. New routes would be steep, loose, run out, and probably require some aid.Climb Description - Southwest Chimney 5.8

A variation to the third lead

Before resorting to an offered shoulder stand, I went around the corner to the right to explore the south face. There I was able to continue to the summit by way of a ramp, traversing the face to the left and then continuing up another to the right. It seemed straightforward at maybe 5.6-7 but poorly protected with the gear we had.

Thanks to the generosity of a great friend and climber, he let me lead the whole thing...my first. I wish I could still share the memory of that day with him."

Getting There

The most straightforward access to the spire is via Cross Mountain Trailhead, approximately 2 miles west of Lizard Head Pass, and 17 1/2 miles from Telluride. From Telluride, go to the state route 145 north/south split. Go south (L) along state route 145 (San Juan Skyway) for 14.0 miles (past Lizard Head Pass) to Cross Mountain Trailhead. From the southwest: from Cortez, go to the state route 145 junction and follow 145 north for about 57 miles to the same location. Hike the Cross Mountain trail (#637) approximately 3 miles to its intersection with the Lizard Head trail, at the base of the formation. Alternately, it is possible to get to Lizard Head from the trailhead at Lizard Head Pass (Lizard Head Interpretive Site); the Lizard Head trail (#505) goes to the base of the ridge, then follows it west to the base of the pinnacle.Take the talus cone to the formation's base, using the faint trail if you can find it. Go to the obvious corner marking the start of the standard route.Red Tape

Lizard Head lies fittingly in the 41,193-acre Lizard Head Wilderness, set aside by Congress in 1980 within the San Juan & Uncompahgre National Forests. In addition to Lizard Head, fourteeners Mt. Wilson, Wilson Peak, and El Diente, as well as numerous other 12,000'+ peaks lie within the wilderness area.The following regulations apply to all Wildernesses within the Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, & Gunnison National Forests (this more or less from the Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, & Gunnison National Forests website):Motorized equipment and equipment used for mechanical transport is prohibited. This includes the use of motor vehicles, motorboats, motorized equipment, bicycles, hang gliders, wagons, carts, portage wheels, and the landing of aircraft including helicopters. Wheelchairs suitable for indoor use are exempt. Be aware, there is a "Region 2 Wilderness Use Restriction, Special Order" ("Possessing or using a wagon, cart, wheelbarrow, bicycle, or other vehicle (Including “game carts”)") in effect as well, ha ha. Weed Free Feed is required on all national forest lands in the Rocky Mountain Region.A summary of the most applicable rules pertaining specifically to climbers in Lizard Head Wilderness is as follows:• A maximum of 15 people, or a combination of 25 people/livestock, is permitted at one time.• Fires are not permitted within 100 ft. of any lake, stream, or National Forest System trail; above treeline; or within Navajo Basin• Don't shortcut a switchback in a trail. Full regulations specific to Lizard Head Wilderness can be found here.When To Climb

July to early September is the main season for climbing Lizard Head Peak. The snow is gone. That being said, take my advice and get a late start. The route is in the shade in the morning and is bitter cold. Some have got frostbite in the summer. You don't want to get too late of a start though. Make sure your off the summit by 11 or 12 at the latest as this would be one nasty place to be with lightning.Winter on Lizard Head Peak is more of a challenge if doing it in the summer is not hard enough. It involves a large dose of suffering. Climbing in double boots and gloves is a must making the climb feel a bit harder than 5.8. No ice screws needed as there was no ice just snow-covered rock. The summit has been one of my favorite experiences in the winter in CO. That being said, I only know of one or maybe two parties climbing it in the winter in recorded history. It's a bit more serious but well worth the effort!Camping

- Alta Lakes Campground: dispersed primitive camping in an alpine setting, no reservations: first-come-first-serve basis, no fee

- Matterhorn Campground: developed campground close to Colorado Highway 145 near Telluride, 28 sites, fee, can make reservations.

- Priest Lake camping area: no designated camping sites, dispersed camping, no services, no fee, vault toilet.

- Sunshine Campground: no reservation needed (first-come-first-serve basis), fee, 15 sites, composting toilets

- Woods Lake Campground: situated in a dense aspen forest, 41 sites, fee, no reservations (first come - first serve basis).

Additional Resources

- Lizard Head on 13ers.com

- Lizard Head on Mountain Project

- Lizard Head on Wikipedia

- Lizard Head trails description great description of trails surrounding Lizard Head

- Denver Post: Lizard Head is one formidable beast

- Lizard Head Wilderness

- Route Description for Lizard Head by Stewart Green

- Lizard Head on List of John

Diggler - Jun 28, 2012 7:11 pm - Voted 4/10

rap' anchor workNot sure if there are other options, but the rap' anchor we used (it puts you ~30' to the R of the standard route P3 start) totally sucked- it held for us to get down, but 2 attempts to pull our ropes were fruitless- I ended up prusiking back up to the anchor TWICE to try to free the lines, but each time, it was still totally impossible to pull them. We ended up leaving a rope left by an earlier party that I'd hoped to return to its owner, & just doing a single-rope rap' off of it (because it was impossible to free our own ropes). Extending the anchor over a prominent edge just below it with some additional chains/quick links, & using a dedicated rap' ring (instead of threading the ropes through 2 chain links would quite possibly do the trick). If a future ascent party familiar with anchor set-up could bring some additional hardware & do some modification, that would be a great community service.

paulinds@earthlink.net - Aug 19, 2020 1:56 pm - Hasn't voted

A variation to the third leadIn late June 1968, Cleve McCarty and I climbed Lizard Head via a variation of the third lead on the south side of the summit block. Using a 150 ft. rope, we split the southwest chimney lead in two. We were unable to protect or climb the short overhang/lie back to start the third lead. Before resorting to an offered shoulder stand, I went around the corner to the right to explore the south face. There I was able to continue to the summit by way of a ramp, traversing the face to the left and then continuing up another to the right. It seemed straightforward at maybe 5.6-7 but poorly protected with the gear we had. Thanks to the generosity of a great friend and climber, he let me lead the whole thing...my first. I wish I could still share the memory of that day with him.

Diggler - Sep 9, 2020 2:14 pm - Voted 4/10

Re: A variation to the third leadThanks, Paul. I included the last part of your route description on the page. I'm glad you had that day with your partner- my best days have been in the hills with friends & loved ones, some of whom are no longer here. I can relate.