|

|

Mountain/Rock |

|---|---|

|

|

56.79712°N / 5.00552°W |

|

|

Hiking, Mountaineering, Trad Climbing, Ice Climbing, Mixed, Scrambling |

|

|

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter |

|

|

4413 ft / 1345 m |

|

|

| "Read me a lesson, Muse, and speak it loud Upon the top of Nevis, blind in mist! I look into the chasms, and a shroud Vapurous doth hide them - just so much I wist Mankind do know of hell; I look o'erhead, And there is sullen mist, - even so much Mankind can tell of heaven; mist is spread Before the earth, beneath me, - even such, Even so vague is man's sight of himself! Here are the craggy stones beneath my feet, - Thus much I know that, a poor witless elf, I tread on them, - that all my eye doth meet Is mist and crag, not only on this height, But in the world of thought and mental might!" John Keats (1795-1821) |

Overview

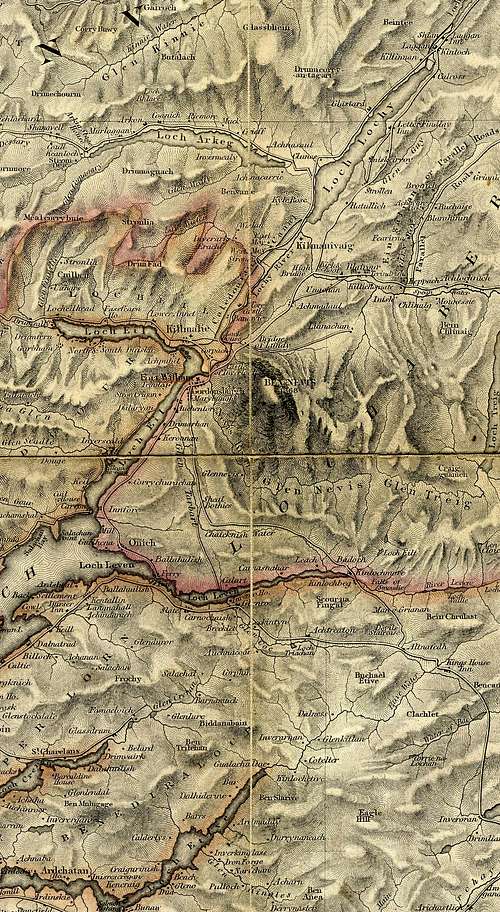

Ben Nevis (1345 m) is the highest point in Scotland and the United Kingdom. It is located at the western end of the Grampian Mountains in the Lochaber area of Scotland, and is only a short distance from the coastal town of Fort William. The mountain's name is obscure in origin with several different theories surrounding its etymology. Ben is of course is the Anglicised word for 'beinn' which means mountain, the origin of the word Nevis howver, is uncertain. One theory is that it's derived from the Irish word 'neamhaise', which means 'terrible', while another suggests that it comes from the Gaelic words 'neamh' or 'nibheis', the former meaning 'a raw atmosphere'; while the latter is commonly translated as 'malicious' or 'venomous'. Any climber who has experienced the mountain while a cold northerly wind blasts snow and spindrift across the summit plateau will be able to attest that Ben Nevis has all of these qualities. A slightly gentler alternative interpretation is that Beinn Nibheis is derived from beinn-neamh-bhathais. 'Neamh' means 'heavens clouds' and 'bathais' means 'top of a man's head'. A literal translation could therefore be "the mountain with its head in the clouds", though the slightly more poetic "Mountain of Heaven" is equally plausible.

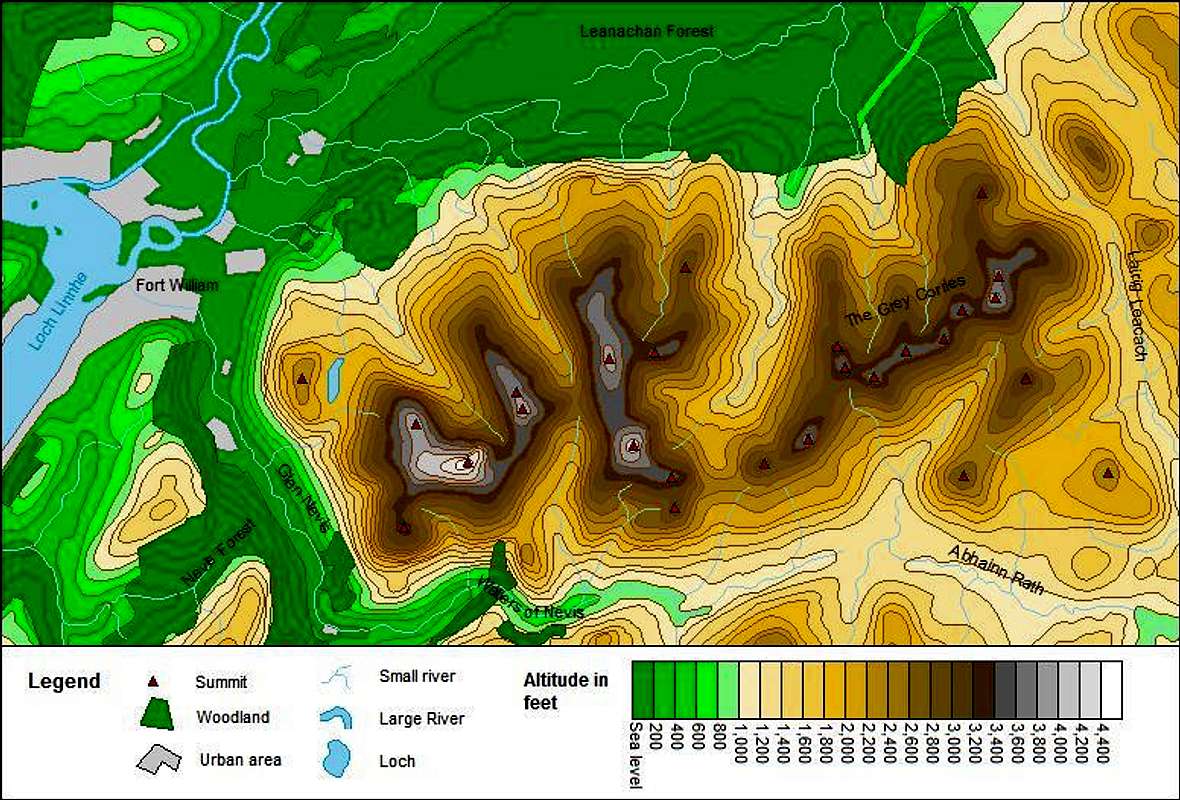

"The Ben" as it is commonly known, marks the western most flank of the aptly named Ben Nevis Range, which is home to some of the country's highest mountains. The views from the summit encompass a considerable part of Scotland's most spectacular scenery, including the mountains of Glen Coe to the south, Sunart Ardgour to the south west, Glen Albyn to the north, Rannoch Moor to the east and faint glimpses of the Isle of Mull in the far south, just beyond the furthest reaches of Loch Linnhe.

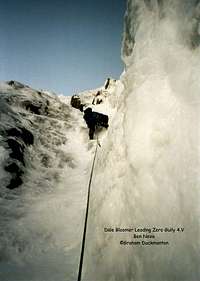

Ben Nevis is the central attraction for winter climbing in the UK, and its gullies and buttresses draw climbers from across Europe. The main winter attraction is its mixed climbing, which involves climbing over a combination of rock, ice and snow. Whether its ridges, gullies or slabs, Ben Nevis has routes that will appeal to all. Compared to the rest of the British Isles, the routes on Ben Nevis are longer than anywhere else, and display an Alpine-like seriousness. In summer, when the snow and ice has melted, the mountain's rock routes come into condition, and vary from easy scrambles to extremely challenging multi-pitch technical climbs. Many of the routes are historically important, having either been first ascended during rock climbings embryonic years in the late 19th century, or have been created by some of the UK's most talented climbers who have been responsible for pushing the ever increasing standards of British climbing.

The mountain receives approximately 100,000 ascents a year with 3/4 of these being via the standard tourist route from Glen Nevis. The southern and western sides are characterised by easy walk ups, while the northern and eastern aspects have enough rock and ice to keep technical climbers of all abilities returning for years.

Summits of the Ben Nevis Range

Ben Nevis gives its name to the Ben Nevis Range, a 16km long spine of mountains that run from Loch Linnhe in the west to Lairig Leanach in the east. Dotted along the chain are a number of Britain’s highest mountains including Aonach Beag and Aonach Mor, both popular winter climbing venues. In the far east the mountains of the Grey Corries are much less frequented and offer a quieter more personal experience than their larger neighbours. The mountains of the range are mapped and listed below.

Okay, a quick explanation about what qualities made these summits eligible to be highlighted in this section - to put it simply they must qualify to be on at least one of the UK’s official mountain lists, any of them. Hover your mouse cursor over the map to find out what lists the peaks belong to. Now I’m sure some of SummitPost’s international users, and probably a good number of British ones, will be scratching their heads and wondering what the hell some of these lists mean (SubGraham anyone!?!). Well I’m not going to tell you, there just isn’t room here to explain them all fully here, however, if you are wondering, here are some links to some helpful pages, several of which are already here on SP – Munro, Murdo, Marilyn, Corbett, Graham.

Interactive Map

Interactive-ish List

| No. | Name | Metres | Feet | Grid Reference | OS-Get-a-Map | Streetmap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Ben Nevis | 1345 | 4413 | NN166712 |  |

|

| 2. | Aonach Beag | 1234 | 4049 | NN197715 |  |

|

| 3. | Ben Nevis - Carn Dearg NW Top | 1221 | 4006 | NN159719 |  |

|

| 4. | Aonach Mor | 1221 | 4006 | NN193729 |  |

|

| 5. | Carn Mor Dearg | 1220 | 4003 | NN177721 |  |

|

| 6. | Carn Mor Dearg - Carn Dearg Meadhonach | 1179 | 3868 | NN176726 |  |

|

| 7. | Stob Choire Claurigh | 1177 | 3862 | NN262738 |  |

|

| 8. | Stob Choire Claurigh - Stob Coire na Ceannain | 1123 | 3684 | NN267745 |  |

|

| 9. | Stob Coire an Laoigh | 1116 | 3661 | NN239725 |  |

|

| 10. | Stob Coire an Laoigh - Caisteal | 1106 | 3629 | NN246729 |  |

|

| 11. | Stob Choire Claurigh - Stob a'Choire Leith | 1105 | 3625 | NN256736 |  |

|

| 12. | Aonach Beag - Stob Choire Bhealach | 1100 | 3609 | NN202709 |  |

|

| 13. | Sgurr Choinnich Mor | 1094 | 3589 | NN227714 |  |

|

| 14. | Stob Coire an Laoigh - Stob Coire Easain | 1080 | 3543 | NN234727 |  |

|

| 15. | Stob Coire an Laoigh - Stob Coire Cath na Sine | 1079 | 3540 | NN252730 |  |

|

| 16. | Aonach Mor - Stob an Cul Choire | 1068 | 3504 | NN203731 |  |

|

| 17. | Ben Nevis - Carn Dearg SW Top | 1020 | 3346 | NN155701 |  |

|

| 18. | Stob Coire an Laoigh - Beinn na Socaich | 1007 | 3304 | NN236734 |  |

|

| 19. | Stob Ban | 977 | 3205 | NN266724 |  |

|

| 20. | Aonach Beag - Sgurr a'Bhuic | 963 | 3159 | NN204701 |  |

|

| 21. | Sgurr Choinnich Mor - Sgurr Choinnich Beag | 963 | 3159 | NN220710 |  |

|

| 22. | Stob Choire Claurigh - Stob Coire na Gaibhre | 958 | 3143 | NN261757 |  |

|

| 23. | Aonach Mor - Tom na Sroine | 918 | 3012 | NN207745 |  |

|

| 24. | Stob Ban - Meall a'Bhuirich | 841 | 2759 | NN254706 |  |

|

| 25. | Meall Mor | 721 | 2365 | NN280705 |  |

|

| 26. | Meall an t-Suidhe | 711 | 2333 | NN139729 |  |

|

Geology

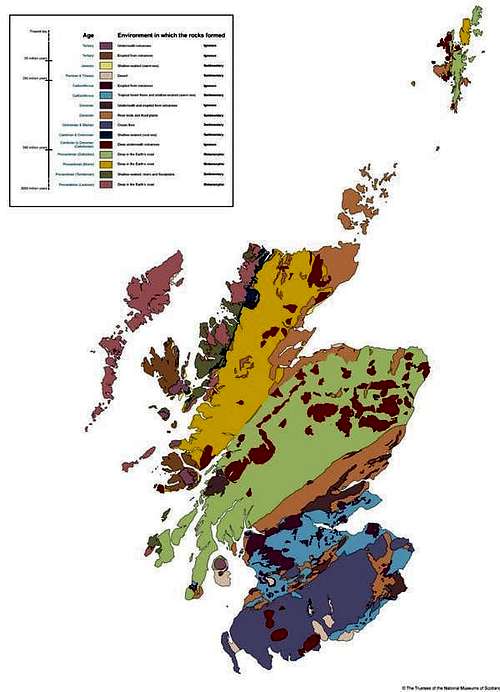

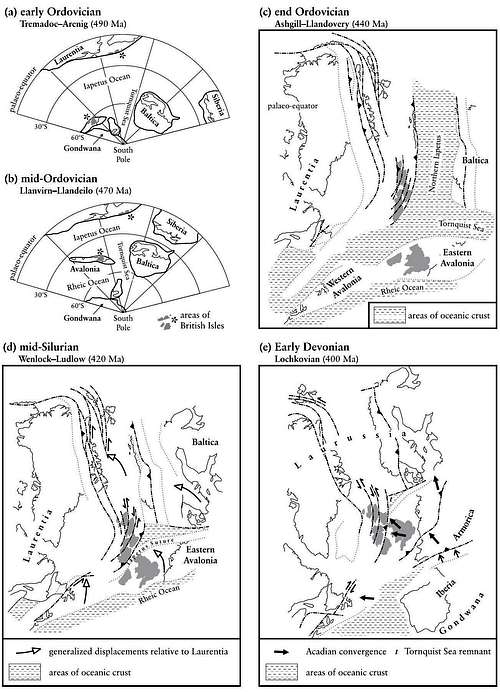

Ben Nevis and its neighbours are the last remnants of what was once one of the world's greatest mountain ranges. The geology of the area is characterised by the Dalradian Supergoup which was produced by intensive metamorphism and deformation arising from 'mountain building', caused by continental collision. Formed during the Precambrian and Cambrian periods between 700 and 600 million (and very possibly as recent as 500 million) years ago (ma), the Dalradian sediments and associated volcanics were originally laid down, or in the case of the volcanics erupted onto, the southern margin of a palaeo-continent known as Laurasia, which is represented today largely by the Precambrian basement rocks of North America, Greenland, the north of Ireland and, of course, the Scottish Highlands.

Laurasia sat on the northern margins of a vast sea known as the Iapetus Ocean, which was created in Late Proterozoic time (1.6 Ga to 0.6 Ga) by the rifting and pulling apart of a large supercontinent known as Rodinia. The opening started sometime around 650 Ma ago and by the beginning of Ordovician (490 to 443 ma), at 510 Ma, the ocean was at its widest, with a possible width of up to 5000 km. On the opposite side lay the supercontinent of Gondwana, consisting of the basements of South America, Africa, India, Australia, East Antarctica and Western Europe (including southern Ireland, England and Wales). A separate continent, Baltica (comprising of what is today Scandinavia and parts of Russia), lay to the north east of Gondwana, separated by an arm of the Iapetus Ocean known as the Tornquist Sea.

During the early Ordovician a micro-continent known as Avalonia (comprising of what today is largely England and Wales), broke away from Gondwana and drifted towards Laurentia. By the late Ordovician, the continental plates of Laurentia, Gondwana and Baltica had started to converge initiating a series of new tectonic and magmatic processes that marked the start of the Caledonian Orogeny. The Dalradian Supergroup underwent deformation and metamorphism as the continental landmasses collided, closing the Iapetus. Geological evidence suggests that Scotland lay on the margin of Laurentia, initially opposite Baltica, while England and Wales lay on the margin of Gondwana/Avalonia, opposite the Newfoundland sector of Laurentia. The terranes were then juxtaposed into their present relative positions by large sinistral (left-lateral) movements on the bounding faults during the later stages of the orogeny. The mid-Ordovician saw the climax of the Caledonian Orogeny in the Scottish Highlands. This ‘Grampian’ Event is particularly well defined in the NE of the Grampian Terrane, where the main deformation episodes and the peak of regional metamorphism are dated by major tholeiitic basic intrusions that were emplaced at around the late Llanvrin time(c. 470 Ma), towards the end of the event. In the central Grampian Highlands and the Northern Highlands Terrane, the comparable event may have been a little later (c. 455 Ma). This continental collision deformed and folded the various sedimentary rocks, which were also metamorphosed, with the recrystalisation of sandstones to quartzites and mudstones to slates. There was also the intrusion of granite magama, derived from the actual partial melting of rocks lower within the crust, where the heat and deformation caused by the continental collision was most intense.

During the early and mid-Silurian (443 to 417 ma) the Iapetus Ocean finally closed along most of its length, with a triangular remnant of oceanic crust around the Laurentia–Baltica–Eastern Avalonia triple junction. This finally disappeared completely by the early Devonian, with the continents welded together along the lines of the Iapetus and Tornquist sutures. The newly formed supercontinent was known as Laurussia. Both the Northern Highlands and the Grampian terranes underwent tectonic uplift during this period, with significant magmatic events occurring on the extreme ‘north-western’ edge of the Northern Highlands. Calc-alkaline magmatism, with subduction-zone characteristics became widespread and voluminous throughout the former Laurentian terranes throughout the Early Devonian period (417 to 354 ma) and large, essentially granitic, plutons (an intrusive igneous rock body that crystallized from a magma below the surface of the Earth) were emplaced at all crustal levels in the Scottish Highland and Eastern Shetland terranes from early Ludlow to early Lochkovian time.

Granitic plutons with lower crustal and mantle characteristics were emplaced at high crustal levels in the Midland Valley Terrane and in the NW part of the Southern Uplands Terrane. High-level granitic plutons and dyke-swarms were emplaced slightly later (Lochkovian to Pragian) in a broad zone that spans the projected position of the Iapetus Suture in the SE part of the Southern Uplands Terrane and in the Lakesman Terrane. Of these, the youngest are those immediately NW of the suture, in the zone in which the Southern Uplands thrust belt was underthrust by Avalonian crust.

The late granitic plutons were emplaced during and immediately following the rapid crustal uplift which produced the Caledonian Mountain chain. High-level crustal extension led to local fault-bound intermontane basins in the Grampian Highland and Southern Uplands terranes and the larger basins of the Midland Valley Terrane. Rapid erosion of the newly formed mountains resulted in the deposition of great thicknesses of continental molasse sediments in these basins during the latest Silurian and Early Devonian (the ‘Old Red Sandstone’).

The Ben Nevis igneous complex is dominated by granitic rocks, with volcanic rocks restricted to an elliptical outcrop in the south. Three principal lithologies were identified as early as 1910 by HB Maufe in his publication 'The Geological Structure of Ben Nevis': (1) Outer Granite, (2) Inner Granite, and (3) a down-faulted block dominated by volcanic rocks. The highest ground is occupied by volcanic rocks that sunk hundreds of metres into an underlying body of still-molten magma during the Late Silurian/Early Devonian. This subsidence was accompanied by the eruption of magma to the surface through an encircling ring fracture. Erosion has removed all trace of the volcanic depression (caldera) that would have been created during this major subsidence event (cauldron subsidence), and the deposits of the accompanying eruption (pyroclastic flows).

Since the mountain's creation, it has been continually eroded by the forces of nature, with the most significant recent events manifesting themselves in the form of the Quaternary era (1.8 Ma – present day) ice ages. During the Late Devensian Glaciation (c. 126 Ka – 15 Ka) the mountain was completely covered by an ice sheet which exceeded 2,000m in height, and was centred over Rannoch Moor radiating glaciers in all directions. The ice sheet helped carve the glens and lochs that surround the mountain today, affecting almost every aspect of the visual landscape. The sheer volume of water held as ice during this period meant that global sea levels were some 130 m lower than today's and the Scottish glaciers would have outflowed rapidly out over a vast tundra plain stretching far into what is now the Atlantic Ocean. A brief warm period known as the Windermere Interstadial (c. 15 ka – 13.5ka) saw the disappearance of the glaciers and the return of vegetation to the British Isles. Owing to the lingering effects of glacio-isostatic depression many of the glens around the mountain would have been inundated by the sea, creating a landscape that may be comparable to the fjords of Norway we see today. Evidence for the type of vegetation that existed in northern and central Scotland during this period is slim, as it was not long before the area saw a return to cold conditions with the onset of the Loch Lomond Stadial, known internationally as the Younger Dryas (c. 12.8 to 11.5 ka). An ice sheet re-formed over much of central Scotland, although this time it would not be large enough to cover Ben Nevis in its entirety. Valley glaciers occupied the major glens, and were funnelled around the major landmasses out to sea. Cirque glaciers occupied the higher corries, with glaciers forming in Coire Leis and the depression now home to Lochan Meall an t-Suidhe. The Ben bares the scars of these ice ages in its striated and polished rocks, morainal ridges, perched boulders and weathered cliff faces that are so familiar to climbers today.

History

Climbing and so on...

Peasants, Poets and... Tourists

It's probably safe to assume that people have climbed Ben Nevis, or at the very least tried to climb Ben Nevis, for as long as there have been people to call the glens surrounding the mountain home. St Columba may even have given its majestic features a sideways glance as he headed up the Great Glen after arriving in Scotland in 563AD. However, since no one made a song and dance about it, we have no firm evidence for such events, so I'm not going to speculate any further on the matter. As with so many of Britain's mountains the first recorded ascent of Ben Nevis was made not for pleasure, but in the pursuit of knowledge, and when on the 17th of August 1771, James Robertson, an Edinburgh botanist, climbed the mountain in search of plant specimens, he became the first known person to reach the summit. A few years later in 1774 the industrialist John Williams climbed The Ben while prospecting for commercially valuable minerals. Luckily for us his efforts were in vain, and instead his expedition provided the first account of the mountain's geological structure.

In 1794 the map of Scotland was revised, a landmark event in Ben Nevis' history as for the first time it proclaimed: “Ben Nevis is, at 4,370ft the highest mountain in Great Britain”, of course with the aid of modern surveying techniques we now know the true height of the mountain to be even greater at 4,408ft (and 6 inches for those who care). Prior to this it had always been thought that Ben Macdui in the Caringorms was Britain's highest mountain. This didn't stop the then local Laird aided by a group of locals from hatching a plan to build a cairn on the summit of Ben Macdui big enough to exceed the height of The Ben, reinstating it as Britain's no. 1 mountain. Unfortunately for the Laird he died before being able to put his plan into action, and his successor, who really didn't care which mountain was the tallest, didn't bother advancing his father's folly any further. The Ordnance Survey finally got round to surveying the area properly in 1847 and it was officially confirmed that Ben Nevis was the highest mountain in Britain, ahead of its eastern rival which had had a loyal posse of supporters arguing its corner since 1794.

While on his 'Northern Tour' the English Romantic poet John Keats climbed the mountain in 1818, comparing the ascent to "mounting ten St. Pauls without the convenience of a staircase". The first symptoms of Keats' ill health, and the development of his hereditary tendency towards cnsumption, can be traced back to this trip and in particular his ascent of Ben Nevis. His condition began whilst on an excursion to Mull where it significantly deteriorated. In a letter to his brother Tom he complained of a 'slight sore throat,' and of being obliged to rest for a day or two at Oban. From Oban he travelled through poor weather to Fort William, where he climbed Ben Nevis in a “dissolving mist”. The ascent, and in particular the descent of the mountain took their toll on the young poet, exacerbating his sore throat. Feverish symptoms set in, and the doctor whom he consulted at Inverness thought his condition threatening, and forbade him to continue his tour. Keats eventually recovered from his illness, however it would be a recurrent feature of his remaining life, which he finally succumbed to 3 years later on the 23rd of February 1821 at the age of just 25.

Throughout the 19th century Fort William and Ben Nevis gradually gained popularity as a tourist destination, helped along by the construction of improved roads, the Napoleonic Wars (which re-directed travellers northwards) and the growing economic strength of the British Empire. Recreational climbing had begun on the mountain as early as 1880 when one adventurous tourist recorded a climb of the North Face via a gully, however, this was a one off event, and the identity of the climber and the name of the gully are now lost in time. The catalyst that turned Ben Nevis into a destination for Britain's pioneering climbers would come in 1894 with the opening of the West Highland Railway.

The Mountaineers Cometh 1889-1918

In 1889 the Scottish Mountaineering Club (SMC) was established under the leadership of the Glasgow mountaineer William W Naismith. The event was unremarkable in the respect that mountaineering clubs had existed in Scotland for a number of years, however they tended to be local affairs with limited technical ambition. The SMC was special because it was countrywide and among its founding members were talented climbers with Alpine experience eager to transpose their skills to the crags and mountains of their native land. The establishment of the club heralded a golden age for climbing on Ben Nevis and for Scottish mountaineering as a whole.

The first recorded rock ascent on Ben Nevis would not, however, be completed by members of the SMC but by J.B. and C. Hopkinson from Manchester, who in 1892 claimed the first ascent of the North East Buttress and descended via Tower Ridge, today two of the best known climbs in Britain. Controversy would later arise when members of the SMC, unaware of the Hopkinson's feat, attempted to claim first ascents for themselves. The SMC began to meet regularly in Fort William, and initially were concerned only with winter routes, laying down a succession of first ascents on The Ben's North East Face. In 1896 Naismith made a remarkable first ascent of the North-East Buttress, which today is still graded as IV, 4. In the same year the rock potential of the mountain was finally fully realised, when the Edinburgh born climber Harold Andrew Raeburn visited Ben Nevis as a guest of the SMC and opened up numerous new routes, including ascents of Observatory Ridge and Buttress. What made Raeburn so remarkable was that many of his first ascents were completed solo, although it could be argued that at a time of hemp ropes, no runners and nailed boots, leading was probably only marginally safer. He described his ascent of Observatory Ridge in The Scottish Mountaineering Club Journal Volume 6, Number 6, September 1901:

“I had failed on short notice to find a companion for the day, so was forced to go solus. One advantage of this, however, is that there is no one to "force the pace," so that rests can be indulged in as much as one is inclined for, and leisure afforded to study the natural surroundings... The weather, which had been close and warm in the morning, became threatening as I entered the great corrie, and soon after down came the rain in real Nevis style. It did not last long, however, and as I gained the foot of the Observatory Ridge, the mists began slowly to roll up their filmy curtains - magnificent transformation scenes of gleaming snowfields, jagged ridges and pinnacles, black frowning cliffs, and long white deeply receding couloirs, coming into view as the visible circle gradually widened...

...The climb begins at no very severe angle, but on rocks distinctly slabby, and poor in holds and hitches. It almost at once becomes a well-defined arete, and higher up is bounded on both sides by very fine almost A.P. precipices. Throughout its whole length it affords less opportunity of deviation from the exact ridge than does its north-east neighbour. Perhaps at no point does it offer such an awkward bit for the solitary climber as the "man-trap" of the North-East Buttress - which can be escaped by descending a little on the right, or up a rather difficult chimney on the left - but I remember three distinctly good bits on it. First the slabby rocks near the foot. Then a few hundred feet up an excellent hand traverse presents itself. It is begun by getting the hands into a first-rate crack on the left, then toe-scraping along a wall till the body can be hoisted on to a narrow overhung ledge above. This does not permit of standing up, but a short crawl to the right finishes the difficulty, at the top of an open corner chimney, a more direct and possibly preferable route.

The third difficulty, and the one which cost most time is rather more than half-way up, where a very steep tower spans the ridge. I tried directly up the face, but judged it somewhat risky, and prospecting to the right, discovered a route which after a little pressure "went." This is a slightly sensational corner, as the direct drop, save for a small platform, is several hundred feet...

...The ridge now eases off and traverses show up as possible, either on to the North-East Buttress on one's left, or to the upper or South-West Observatory Ridge to the right. The gully on the left now holds heavy snowdrifts. The climbing, however, is far from over, numerous steep or slabby bits engage the climber's vigilance; but at length the last rocks are gained, where the crest of the ridge plunges under the great snowfield that girdles this face of the mountain, still at midsummer presenting in places icy cornices 20 feet high.”

Raeburn was also a skilled winter climber and in 1906 completed a first ascent of Green Gully in Coire na Ciste, at the time the hardest ice route yet completed on the mountain, and is still graded as IV, 4. Raeburn would later become leader of the 1920 reconnaissance expedition to Kangchenjunga and the 1921 reconnaissance expedition to Mount Everest.

In 1911 Henry Alexander Jr, son of a Ford dealership owner in Edinburgh, drove a 20 horse-power Model T Ford to the top of The Ben as a publicity stunt. The exploit involved 10 days of reconnaissance work - finding and checking a drivable route to around half way up the mountain, and placing bridging planks over impassable gullies and streams. It took three further days to drive the car to the halfway point and two more days to cover the rest of the distance to the summit. Alexander was helped by a large support team who would haul him to safety whenever the car sank in boggy ground. Which it would do frequently on the lower slopes of the mountain, often axle deep.

On returing to Fort William, Alexander was hailed a hero, and after only some minor adjustments to the breaks, and no other repairs necessary, he drove his car back to Edinburgh. In 1928 he returned to Ben Nevis' summit, this time in a Standard New Ford (Model A Ford).

Between the Wars and Beyond 1918-1950

First ascents continued to be recorded throughout the early 20th century, with a quiet period during the First World War. In 1926 work began on a mountain hut at the foot of the North East Face. It was completed in 1929 and was named the Charles Inglis Clarke Memorial Hut (normally abbreviated to CIC Hut) in honour of the son of Dr William and Mrs Jane Inglis Clarke, who was slain during the First World War. Dr Inglis Clarke and his wife were accomplished climbers in their own right, regularly climbing with Harold Raeburn and having completed numerous first ascents themselves. The hut remains in use today and at 680 m above sea level it is Britain's only 'Alpine' type hut and can be booked out from the Scottish Mountaineering Club.

The erection of the CIC hut helped speed up development between the wars. Alan T Hargreaves of the Fell and Rock Climbing Club partnered with George Graham MacPhee opened up Route 1 (Severe 1931), the chimney up the left side of Carn Dearg. Hargreaves also managed a first ascent of the Rubicon Wall (Severe 1933) on Observatory Buttress wearing plimsolls. The inter-war period would however be dominated by MacPhee and another great climber named J. B. Bell. Bell excelled in both summer and winter climbing opening numerous lines on the Orion Face. His exploration of the face culminated in The Long Route (VS 1940), which is one of the only rock routes in Britain that can be said to be of alpine quality. MacPhee added many more routes of his own, the best probably being the Trident Buttress, and wrote a new guidebook based on his considerable experience. Macphee also added several significant winter routes including Glover's Chimney (III, 4) with George Williams and Drummond Henderson; Cousin's Buttress (III 1935), Good Friday Climb (III 1939) and South Gully (III 1936), the latter of which he climbed solo.

During the Second World War climbing on The Ben would be dominated by Brian Pinder Kellet. Kellet was a pacifist stationed in Lochaber as a forestry worker at Torlundy. In his spare time he climbed all the known routes as well as adding many of his own, often solo, including Route II (Severe 1943) on Carn Dearg and Left Hand Route (VS 1943) on the Minus Face. Kellet's climbing, particularly his solo ascent of Kellet's Route (HVS 1943) was an enormous leap in technical difficulty, which would not be matched for another 10 years. He also made attempts to climb Sassenach, but was beaten by the slabs out of Centurion Corner. In 1944 he was tragically killed, along with his climbing partner Nancy Forsyth, in a fall on Carn Dearg. Kellet's death created a void in exploration that took years to fill. The only other ascents of note were made by Ian Ogilvie in 1944 who climbed numerous new routes on Carn Dearg and the Norh East Face, but was killed in the Caringorm's later that year; and by H. Carsten and Tommy McGuiness who climbed The Crack (HVS 1946) on Raeburn's Buttress.

The Modern Era 1950-Present Day

The 1950's heralded a second golden age for climbing on Ben Nevis with now legendary climbers flocking to the mountain, drawn by its infamous rock and ice. Sassenach was finally conquered in 1954 by Don Whillans and Joe Brown who snatched the prize from a team from Aberdeen consisting of Tom Patey, Bill Brooker and A. Taylor. The first half of the 1950s would be dominated by Whillans, alongside Bob Downes and Mike O'Hara who added a proliferation of new routes including Centurion and The Shield (both HVS, 5a), both in 1956. In March 1952 Dan Stewart and W.Forster of Edinburgh University Mountaineering club climbed the Observatory Buttress Direct (V, 5). Later in the decade and into the 1960s home grown climbers such as Robin Smith, Dougal Haston, John McLean and J.R Marshall would come to the fore, completing numerous routes including The Bat (E2, 5b) in 1959, The Bullroar (HVS, 5a) in 1961 and Torro (E1, 5b) in 1962. Marshall would go on to climb all the existing routes and produced a new guidebook based on his experience.

Throughout the 1950s competition to climb new and harder winter routes on the mountain intensified considerably. In 1957 Hamish MacInnes, Tom Patey and Graham Nicol climbed Zero Gully (V, 4) in just over five hours. Remarkably on the same day Len Lovat and Donald Bennet made a first ascent of Number 3 Gully Buttress (III), and Malcom Slesser and Norman Tennent added a direct finish to Cresta (III). 1959 would see even more now classic routes added to the mountain. Robin Smith and Dick Holt climbed the Tower Face of the Comb (VI, 6), a route so technically demanding that it would not be repeated for another 25 years or so. Later that winter Smith and Holt produced another feat of technical brilliance and endurance by climbing the first winter route on the Orion Face. The Smith-Holt Route (V, 5) was roughly based on J.B. Bell's The Long Route, and took the pair 12 hours to complete. In the same year a team consisting of Jon Alexander, Ian Clough, Don Pipes and Robin Shaw completed a first ascent of Point 5 Gully (V, 5), one of the world's most famous ice routes. Using over 60 rock and ice pegs the team fixed 300m of rope in the gully, and after more than 40 hours of work spread over 6 days the team was eventually successful. Their method of ascent proved to be extremely controversial, and they received considerable criticism from their Scottish peers. The team, however felt that they were completely justified in their actions and Shaw wrote to Glasgow University Mountaineering Journal stating “I have no doubt that Point Five Gully will be climbed in less time, but a party will be very lucky to find it in suitable condition to climb in one day”. He was of course proved wrong.

The SMC meet of 1959 bought fourth even more new lines on the mountain, with Jimmy Marshall, Tom Patey and Bill Brooker recording first ascents of the 1,500 m long route, The Winter Girdle (IV, 5) and Raeburn's Buttress (IV, 5); and Ronnie Sellars and Jerry Smith adding Pinnacle Arête (IV, 4). Later that winter Marshall went on to complete Smith's Gully (V, 5), and Minus Two Gully (V, 5) the hardest gully climb on the mountain in 15 years. In the February of 1960 Marshall teamed up with Robin Smith and recorded six new lines and proved Robin Shaw wrong by completing Point Five Gully in a mere seven hours. By this point the quality of ice climbing on Ben Nevis had not only exceeded that anywhere else in Scotland but was now comparable with elsewhere in the World. The Cornuau-Davaille on the North Face of Les Droites (ED1 1955) was the only route of equivalent difficulty in the Alps at the time. Smith was killed two years later whilst climbing in the Pamirs, and subsequently the next ten years saw a drop in the pace of development on Ben Nevis and an increase in the level of activity on the mountain rather than a rise in standards.

The 1970's bought fourth the discovery of the magnificent Central Trident Buttress by members of the Dundee based Creagh Dhu Mountaineering Club. Carn Dearg attracted the most attention throughout the decade, and its potential was unleashed in 1977 with the arrival of two teams with the intention of claiming the crackline on the West Face. Titan's Wall (E3 6a) was snatched by Mick Fowler and Phil Thomas, while the Big Banana Groove was ascended in part by Dave Cuthbertson, Dougie Mullin, and Willy Todd as Caligula a year later in 1978. The other notable development of 1977 was Rab Carringon and Ian Nicolson's ascent of the Gargoyle Wall (VI, 6), one of the first pure mixed routes to be climbed on the mountain. The main event of the 1970s would come in 1978 when Fowler and V. Saunders ascended the steep right flank of the Carn Dearg Buttress producing the Shield Direct (HVS 5a). The event marked a major leap in modern climbing standards.

In 1983 M Hamilton and Rab Anderson finally nabbed Banana Groove (E4 6a). The other main event of 83' would be the ascent of the arête, Titan's Wall by Pete Whillance and Anderson, to give Agrippa which at E6, 6b is The Ben's hardest summer route. The 1980s saw a significant step forward in the way thin winter face routes were climbed when Cuthbertson and Rudi Kane completed Stormy Petrel (VII, 6), a route that has been climbed by few others since. With improvements in the quality of gear and the ways in which protection could be used, harder and harder routes were added throughout the decade, notably Diana (V, 5), Bydand (V, 5), Point Blank (VII, 6), Centurion (VIII, 8), Riders on the Storm (VI, 5), The Black Hole (VI, 6), Match Point (VI, 5), Tramp (IV, 4), Lost the Place (V, 5), Satanic Verses (VI, 5) and Pinnacle Buttress Direct (V, 5).

The 1990s saw such a proliferation of activity on The Ben, that its difficult to summarise it all in the space I have; so I shall highlight only the most significant events, but be aware that it really doesn't do the decade justice. The late 80s early 90s saw huge developments in mixed climbing, with a number of hard summer routes falling to winter first ascensionists. Notable examples include Cutlass (VI, 7), The Groove (V, 6), Clefthanger (VI, 6), and Kellet's North Wall (VII, 7). The ascent of Cornucopia (VII, 9) in 1996 by Simon Richardson and Chris Cartwright was a landmark in the development of mixed climbing on Ben Nevis as it demonstrated that the mountain was capable of providing winter only mixed routes of the highest difficulty, and that it wasn't necessary to follow summer lines to find protection. The following year the pair added South Sea Bubble (VII, 7) and Darth Vader (VII, 8), the latter of which they considered to be the mountain's greatest prize.

Very few new rock ascents were made during the 1990s, a trend which has continued into the present decade. In 1993 Noel Williams found three short routes below North Trident Buttress including Tuff Nut (HVS) and in 1994 Dave Jenkins and Colin Stead established Walking Through Fire (VS) on the Douglas Boulder. A year later Colin Moody added Devastation (E1) on the South Trident Buttress and Long Division (E1) on the Minus Face.

The early years of the 21st Century started badly for climbing throughout Britain, with the Foot and Mouth Crisis of 2001 preventing access to many areas from the end of February. The Ben was one of the first mountains to be reopened and Cartwright and Richardson added several more hard mixed routes including Face Dancer (VI, 6), Atlantis (VI, 6) and Appointment with Fear (VII, 6). The decade saw many second ascents of some of Ben Nevis's hardest routes, as well as the addition of several good new ones including the first winter ascent of the Slab Climb (VI, 7) by Andy Nisbet and Jonathan Preston and the prominent ice groove of Maelstrom (VI, 6) by Cartwright and Richardson. The finest ascent of the 2002 season was Blair Fyffe's Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner (VII, 7).

On 16 March 2008 Dave MacLeod and Joe French competed the Grade XI, 11, 275 m long Don't Die of Ignorance, the hardest winter climb yet to be completed on Ben Nevis, and one of the hardest routes in Britain. Details of the feat and some stunning photography can be found over on Dave's blog.

Ben Nevis Observatory

It was in 1877 that the idea of a meteorological observatory on the summit of Ben Nevis was first aired, and in 1878 following an ascent of the mountain by 73 year old David Milne Home, chairman of the Council of the Scottish Meteorological Society (SMS), the go ahead was given for plans to be drawn up. At the time Great Britain was one of the worlds leading super powers leading the world in feats of engineering and scientific achievement. High-level observatories were being established throughout the Empire and other parts of the world in order to obtain routine observations at higher levels in the atmosphere, and hence improve the understanding of the vertical structure of weather systems. Owing to its westerly position, directly in the path of Atlantic storms, Ben Nevis was considered to be of particular importance. The SMS applied for government funding, however they were met with little success, being referred from one government department to another.

While the SMS had been eagerly hunting for funding for their proposed observatory a remarkable character, Clement Lindley Wragge, who had been superhumanly running 3 meteorological stations at varying altitudes near his home in Cheshire, offered in 1881 to make daily ascents of Ben Nevis during the summer of that year; with the SMS providing instruments. This offer was heartily accepted and Wragge, occasionally relieved by an assistant, climbed the mountain daily from June to mid-October, starting out at 5 a.m. Weather conditions on the mountain were often appalling and his subsequent bedraggled appearance led to his local nickname of “Inclement Wragge”. His wife made comparison observations in Fort William. Wragge conducted his observations unbroken between 1 June to 14 October and for his efforts he was awarded the Scottish Meteorological Society's Gold Medal. The following year during the summer of 1882, he carried out a more ambitious programme with the help of two assistants, one of whom was Angus Rankin who later gained employment at the permanent observatory. In 1883 the daily climbs were continued by the assistants.

The observations of Wragge and his assistants showed that the weather conditions at the top of the mountain, even in summer, were much more severe than previously thought and that it would be impossible to use standard automatic recording instruments, with a single observer to maintain their operation. Manual recording would be essential and the only way to effectively achieve this would be the construction of a permanent building near the summit.

Wragge’s exploits received wide publicity and when a public appeal was launched by the SMS in 1883, there was a very rapid response from throughout the UK. Funds came in so quickly that a start could be made that summer on building the access pony track (with a gradient of not more than 1 in 5) and the first stage of the summit observatory. The work was completed by a local contractor from Fort William called James McLean, and the final rise onto the summit is named McLean's Steep in his honour.

On 17 October 1883 the building was declared open by proprietor of the Ben Nevis estate, Mrs Cameron Campbell of Monzie, who ascended the mountain on a pony. The scene was set as a northwesterly airstream covered Scotland that morning depositing snow above 700m, giving the inaugural party a taste of what life might be like at the new observatory. There had been 19 applicants for the position of Superintendent, including one from Clement Wragge, but the directors decided to appoint Robert Traill Omond instead and a disappointed Wragge left for Australia. Wragge would go on to carve a distinguished career for himself as a meteorologist in Australia and India. Among his achievements were the establishment of an extensive network of observatories in Queensland, as well as stations on Mount Wellington, Tasmania, and Kosciuszko, New South Wales. He was also responsible for the convention of naming cyclones after people. Back on Ben Nevis, Omond, who had worked with Professor Tait at Edinburgh University, proved to be an excellent successor to Wragge.

Life proved tough for the observatory's meteorologists who experienced a particularly cold and stormy first winter. Some days taking observations became impossible, with the observers either unable to dig themselves out or confined to the building when it was too dangerous for them to attempt to reach their instruments. The following summer the building was enlarged, with a prefabricated wooden tower being added to provide an exit in deep snow conditions and to support the Robinson anemometer. Hourly observations were taken in summer and winter - often under the most appalling conditions. Supplies were brought up by pack ponies along the Pony Track (obviously) which had been constructed alongside the observatory.

The observatory provided an excellent location for a field laboratory, and scientists from many different disciplines conducted experiments there. The most famous of these was probably C T R Wilson who is best known for developing the cloud chamber, one of the most important tools used in atomic physics research and for which he received the Nobel Prize for physics in 1927. Wilson was employed as a relief observer for two weeks during the summer of 1894 and was so impressed by the glories and corona that he saw, that he began laboratory experiments on clouds formed by the expansion of moist air. These experiments were the beginning of a highly distinguished scientific career. Among those who worked for longer periods at the observatory were R C Mossman, who was the meteorologist on the Scottish Antarctic Expedition of 1902-1904 and W S Bruce, the expedition's leader. Mossman and Bruce's time at the observatory proved escellent training for their 1902 voyage to the Antarctic in the whaler Scotia. Bruce in particular appeared to have enjoyed his time on Ben Nevis. He not only took observations with the two other observers but plotted bird migrations and made a collection of insects - now in the museum in Edinburgh. During his stay on the mountain he was sent a pair skis by William Burn-Murdoch - probably the first in Scotland. Bruce was one of the first British polar explorers to become proficient at skiing, and in 1907 was honoured with the position of first President of the Scottish Ski Club. On one occasion his love of skiing almost proved fatal when he just managed to save himself from plunging over the North East Face of Ben Nevis.

The opening of the path and observatory made an ascent of Ben Nevis increasingly popular, all the more so after the arrival of the West Highland Railway in Fort William in 1894 which carried tourists and members of the recently formed Scottish Mountaineering Club to the foot of the mountain. Around this time the first of several proposals were made for a rack railway to the summit, luckily for us none of which came to fruition. Some time after the observatory started operating, an enterprising Fort William hotelier opened the diminutive Temperance Hotel near the summit and connected to the main building of the Observatory. The hotel was run by two local ladies on his behalf. It had four bedrooms available at ten shillings per person for dinner, bed and breakfast. This hotel continued receiving guests right until the end of the First World War, long after the observatory itself had ceased operating.

The annual cost of running the observatory was £1000, but government grants only equalled £350. Several times closure was threatened, but generous donations from private individuals temporarily alleviated the problem. Then in 1902 the SMS was told that the grants would be withdrawn at the end of that year. There was a huge public outcry in Scotland and a Treasury Committee of Enquiry was set up to look into the administration of the annual grant of £15,300 to the Meteorological Council. Sufficient funds were obtained to keep the observatories going until the Committee was due to report in 1904, but they only recommended that the annual grant of £350 should continue, ignoring the evidence from the SMS that the sum required was about £950 per annum. The Directors issued a Memorandum which said "It is to the Directors a matter of profound disappointment that in this wealthy country it should have been found impossible to obtain the comparatively small sum required to carry on a work of great scientific value and interest, and that they are now obliged to dispose of the Observatory buildings and dismiss the staff". The Observatory finally closed on October 1st 1904 after operating for only 21 years. W S Bruce (mentioned above) was most upset by the closure and wrote: “It is significant to note how the Argentine government willingly spent money on a scientific object such as this while nearer home we have the deplorable occurrence of an ignorant government closing the most important meteorological observatory in its country”. The site remained partially occupied for a further 12 years with one room of the keepers hostel and a refreshment room remaining open during the summer months. The observatory fell into disrepair, helped along by a fire in 1932 and the actions of both weather and unthinking climbers.

Today the ruins of the observatory are a prominent feature on the summit plateaux. For the benefit of those injured or caught out by bad weather, an emergency shelter has been built on top of the observatory tower. It should be noted however, that it is only a rudimentary shelter and should not be relied upon as a sanctuary if things go wrong. Although the base of the tower is slightly lower than the mountain's true summit , the roof of the shelter overtops the trig point by several feet, making it the highest man-made structure in Britain. A war memorial to the dead of World War II is located next to the ruins.

Ben Nevis Race

The first recorded run to the summit of Ben Nevis and back took place on the 27th of September 1895. The course was originally run from the old post office, and the first person to complete it was a local hairdresser, tobacconist, dog breeder and general 'gad about town' (not my words), called William Swan, who set the record at 2 hours 41 minutes. William Thomas Kilgour described the event in his book Twenty Years on Ben Nevis (1905):

"(On Monday) Mr William Swan, tobacconist here, ascended Ben Nevis with the object of establishing a record. The day was exceedingly hot and unsuitable for mountaineering, but, notwithstanding, Mr Swan managed to reach the summit, and, after drinking a cup of Bovril, returned to Fort William in the incredibly short space of 2 hours 41 minutes. This is believed to be a record."

Swan's record made him something of a celebrity, and over the following years men from far and wide descended on Fort William with the aim of reaching Ben Nevis' summit and beating the hairdressers time.

The first competitive race wasn't held until 3 years later on the 3rd of June 1889, when the race was run by 10 competitors under the rules of the Scottish Amateur Athletic Association. The new race was slightly longer than the one run by Swan, starting at the Lochiel Arms Hotel in Babavie. The winner was 21-year-old Hugh Kennedy, a gamekeeper at Tor Castle, who finished in 2 hours 41 minutes, coincidentally exactly the same time recorded by Swan back in 1895.

Regular races were held until 1903, when on that year two events were held. The first was a shorter race starting at Achintee, at the foot of the Pony Track, and finished at the summit; it was won in just over an hour by Ewen MacKenzie, an observatory roadman. The second race started at Fort William's new post office, and again the roadman MacKenzie won, lowering the record to 2 hours 10 minutes. He held the record for 34 years, probably helped by the fact that the race wouldn't be held for another 24 years.

Sporadic attempts were made to revive the event, but the modern Ben Nevis Race really began in 1937 with the presentation of the MacFarlane Cup by the late George MacFarlane, former provost of Fort William. Today the race is well established and takes place on the first Saturday in September. Up to 500 entries are accepted from suitably qualified hill runners. Due to the serious nature of mountain running, known in the UK as Fell Running, entry is restricted to those who have completed three fell races, and runners must carry waterproofs, a hat, gloves and a whistle; anyone who has not reached the summit after two hours is turned back. The race starts and finishes at the Claggan Park football ground, is 16km long and has 1,340 m of ascent. The record for men stands at 1 hour, 25 minutes and 34 seconds and is held by Kenneth Stuart of Keswick AC; for ladies the record is 1 hour, 43 minutes and 25 seconds, held by Pauline Haworth, also of Keswick AC. Most people take over six hours. Both records were set in 1984. In 1972 the Connochie Plaque was instituted and is awarded to those runners who complete 21 Ben Nevis Races. The late Eddie Campbell of Fort William holds the record for the most Ben Nevis Races having run an incredible 44 consecutive times and winning it on no less than three occasions.

For information about entering the race click HERE!

The Summit Trig Point

On the summit of Ben Nevis, next to the ruins of the observatory, you will find the Triangulation Pillar. This is more often than not simply called the 'Trig Point.' [Grid reference NN 166(5) 712(8)]. Many experienced climbers and walkers will tell anyone who will listen that the Trig Points are always found at the highest point on a hill or mountain, this, however is a common misconception. Trig points are actually sited so they can be seen from the other trig point positions on the surrounding hills, in many cases this is the highest point, but not always. It is important that these are positioned in this manner as each Trig Point forms a corner' of a triangle, polygon or other geometric shape. This is used to produce an accurate framework which in turn is used to provide very exact fixings to the latitude and longitude, thus allowing the map maker and others to be able to work out their precise location any where in Britain.

Triangulation and heightening information kindly supplied by Ordinance Survey.

Wildlife and Conservation

The wildlife of Ben Nevis Range is protected by the Ben Nevis Special Area of Conservation (SAC), and is therefore recognised by the European Community’s Habitats Directive. Ben Nevis SAC covers an area of 9317.18 hectares (93 square km) and includes within its boundaries many of Scotland’s highest mountains including Ben Nevis itself, Carn Mor Dearg, and Aonach Beag.

The area is rich with important habitats, according to the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC), who are the statutory adviser to Government on UK and European nature conservation, with the exception of Beinn Dearg and the Loch Maree Complex in the north, Ben Nevis has the most extensive development of Siliceous alpine and boreal grassland in the western Highlands. On the summit plateau of Aonach Mór Carex bigelowii – Racomitrium lanuginosum moss-heath occurs as the highest extensive stand in the UK. The normal dominant Racomitrium lanuginosum is in part replaced on Aonach Mór by R. canescens (sensu lato) , which provides affinities with the vegetation of Iceland and Jan Mayen. The R. canescens is associated with open, wind-blown sandy areas where there is active erosion and deposition of sand caused by the exceptionally high altitude and exposure. Other wind-eroded areas among Carex – Racomitrium moss-heath may be colonised by three-leaved rush Juncus trifidus, and the national rarity curved wood-rush Luzula arcuata. Frequent arctic-alpines in the Carex – Racomitrium moss-heath include least willow Salix herbacea, spiked wood-rush Luzula spicata, J. trifidus and moss campion Silene acaulis. Nardus stricta – Carex bigelowii grass-heath is extensive and occurs mostly in corries and in hollows on ridges where snow lies late. Carex bigelowii – Polytrichum alpinum sedge-heath occurs on the higher summits where snow lies late in hollows and is more abundant on this site than on any other site in the western Highlands. These communities are associated with some of the most extensive moss-dominated late-lie snow beds (Polytrichum sexangulare – Kiaeria starkei and Salix herbacea – Racomitrium heterostichum snow-beds) outside of the Cairngorms.

With Beinn Dearg, Ben Nevis represents high-altitude sub-types of Alpine and subalpine calcareous grasslands in the western Scottish Highlands. The site contains moderately extensive areas of both Festuca ovina – Alchemilla alpina – Silene acaulis dwarf-herb community and Dryas octopetala – Silene acaulis ledge community. There is a moderately rich arctic-alpine flora including alpine mouse-ear Cerastium alpinum, arctic mouse-ear Cerastium arcticum, rock sedge Carex rupestris, hair sedge C. capillaris, mossy saxifrage Saxifraga hypnoides and alpine meadow-rue Thalictrum alpinum. There are relatively low grazing levels on the northern slopes of Ben Nevis, enabling the high-altitude Dryas heath community to survive on the open hillside, rather than being restricted to inaccessible ledges.

Ben Nevis is also representative of high altitude siliceous scree in the north-west Scottish Highlands. The site contains extensive screes of quartzite and granite, with the most extensive known development in the UK of snow-bed screes with parsley fern Cryptogramma crispa, alpine lady-fern Athyrium distentifolium and other ferns. The screes found in the site are diverse, with a range of characteristic species. There is an abundance of acid rock-loving species in high-altitude glacial troughs, corries and on summit ridges. These include a number of montane bryophytes and arctic-alpine vascular plants, such as curved wood-rush Luzula arcuata, wavy meadow-grass Poa flexuosa, hare’s-foot sedge Carex lachenalii, alpine tufted hair-grassDeschampsia alpina, starwort mouse-ear Cerastium cerastoides, alpine speedwell Veronica alpina and Highland saxifrage Saxifraga rivularis.

Within the Ben Nevis site limestone occurs up to high altitude, notably on Aonach Beag, and this is one of the richest areas outside of the Breadalbane range and Caenlochan for arctic-alpines of calcareous rocks. Calcareous rocky slopes with chasmophytic vegetation are well-represented and Ben Nevis is notable for populations of a number of very rare species which are associated with calcareous outcrops of rock faces in high gullies. These include tufted saxifrage Saxifraga cespitosa, drooping saxifrage S. cernua and Highland saxifrage S. rivularis. Other national rarities of rock outcrops include glaucous meadow-grass Poa glauca, alpine meadow-grass Poa alpina, arctic mouse-ear Cerastium arcticum and alpine saxifrage Saxifraga nivalis. Other arctic-alpines represented include rose-root Sedum rosea, alpine scurvygrass Cochlearia pyrenaica ssp. alpina, mountain sorrel Oxyria digyna, holly fern Polystichum lonchitis, mossy saxifrage Saxifraga hypnoides and purple saxifrage S. oppositifolia.

The area is representative of high-altitude Siliceous rocky slopes with chasmophytic vegetation in north-west Scotland. Crevice communities occur extensively on acidic crags up to a very high altitude and have a diverse flora, with characteristic examples of the commoner arctic-alpine species. The site also supports a number of rare species, including hare’s-foot sedge Carex lachenalii, spiked wood-rush Luzula spicata and alpine speedwell Veronica alpina.

Wildlife in the area is in abundance with some 50 species of flower, 30 species of fern, some 50 species of moss, 5 species of clubmoss, 9 species of Horsetail, around 50 species of lichen, around 50 species of fungus and fungoid, over 50 species of quillwort, stonewort and liverwort, and 16 species of conifer occupying the valleys and mountain sides of the area. Countless insects feed upon and live within this vegetation with some 20 species of butterfly, around 40 species of moth, around 50 species of beetle, around 50 species of spider, 3 species of grasshopper, 8 species of dragonfly,16 species of hymenoptera (bees, wasps and ants), as well as countless other species of insect. There area also around 40 species of molluscs, 1 species of flatworm and 1 annelid.

Within the sites lakes, streams and marshes live a plethora of amphibians and fish including 1 species of Lamprey, and 7 species of bony fish including Brown Trout, Atlantic Salmon, and European Eel. Of the amphibians living in the area are the Common Frog, Common Toad and Palmate Newt.

Although rarely seen reptiles also live within the area in the form of the Common Lizard and Slow-worm.

Birds include the Common Raven, Eurasian Dotterel, European Golden Plover, Meadow Pipit, Merlin, Red Kite, Ring Ouzel, Rock Ptarmigan and Twite.

Among the species of mammals that can be found there are American Mink, Eurasian Badger, Eurasian Red Squirrel, European Mole, European Otter, Mountain Hare, Pine Marten, Red Fox, Red Deer, Roe Deer, Sika Deer, West European Hedgehog, Wild Car, Wood Mouse, Eurasian Pygmy Shrew, Eurasian Common Shrew, Bat (Chiropetra) and the Brown Long-eared Bat.

General site character

Bogs. Marshes. Water fringed vegetation. Fens (8%) Heath. Scrub. Maquis and garrigue. Phygrana (20%) Dry grassland. Steppes (11%) Humid grassland. Mesophile grassland (7%) Alpine and sub-alpine grassland (20%) Broad-leaved deciduous woodland (4%) Inland rocks. Screes. Sands. Permanent snow and ice (30%)

Information provided by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee

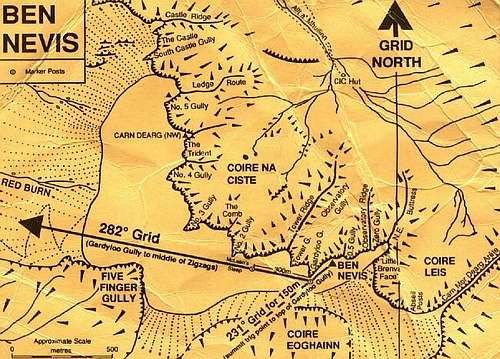

Routes

This section summarises some of the most popular routes on Ben Nevis. As The Ben is so well explored only the routes that are directly associated with the mountains itself have been listed here. For example, for legibility's sake the proliferation of quality single and multi-pitch climbs found in Glen Nevis and the numerous winter climbs on the Aonachs have not been included on this page. For details of scrambling, climbing and winter routes that are more closely associated with Ben Nevis' subsidiary peaks and outlying crags take a look at their own pages (providing they exist).

For a more detailed description of the various routes available I recommend the following guidebooks:

Scrambles in Lochaber by Noel Williams Ben Nevis Rock and Ice Climbs by Simon Richardson Winter Climbs Ben Nevis and Glencoe by Alan Kimber Scotland’s Mountain Ridges by Dan Bailey Rock Climbing in Scotland by Kevin Howett

Scrambling

Ben Nevis has many scrambles and low end technical climbs up its numerous faces, only a few of which are listed below. Owing to the mountains extraordinary ability to hold snow and ice for much of the year, some routes are only possible for a couple of months during high summer. On the other hand in when snow and ice abounds, some scrambles become fun winter routes and can be completed regardless. The following section is not intended to be a comprehensive guide to the mountains scrambles, but more of a way of pointing the reader in the right direction. For a full description of most of these routes see Noel Williams' excellent guide, Scrambles in Lochaber.

| Face/Peak | Route | Grade |

| Meall an t-Suidhe | Central South-West Buttress | 2 |

| Right-hand South-West Buttress | 1 | |

| Western Flank | Surgeon's Rib | 1 or 3 |

| Mam Beag, Polldubh | Scimitar Ridge | 1/2 |

| Meall Cumhann | Traverse of Meall Cumhann | 2 |

| North-East Face | Castle Ridge | 4 |

| Ledge Route | 1 | |

| Number 4 Gully Buttress | 3 | |

| Central-North Ridge | 2 | |

| Raeburn's Easy Route | 1/2 | |

| The Crossing of Tower Ridge | 4 | |

| Carn Mor Dearg | East Ridge of Carn Dear Meadhonach | 1 |

| Carn Mor Dearg Arête | 1 | |

| The Aonachs | West Ridge of Aonach Mor | 2 |

| The Headwall of An Cul Choire | 3 | |

| The Grey Corries | The Giant's Staircase of Coire Claurigh | 2 |

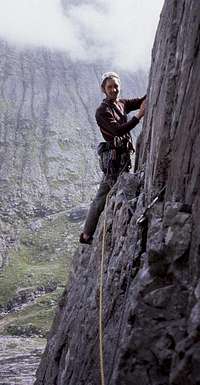

Rock Climbing

Climbing on Ben Nevis is of a traditional affair with most lines situated on the mountain's precipitous north east face. As with the mountain's scrambles, some routes are only climbable for a short period over the summer, with lingering snow and ice rendering them unscalable for most of the year. The mountain boasts climbs for all abilities, many of which have now become classic routes having been first climbed by iconic characters of British climbing history, such as Robin Smith, Joe Brown and Don Whillans. There is a certain amount of overlap between the harder scrambling and the easier climbing routes, and so in some cases routes have been listed in both sections. Routes and grades are listed with the aid of Simon Richardson's guidebook Ben Nevis Rock and Ice Climbs. Please refer to this or other recommended guidebooks for further descriptions.

| Coire Leis | ||||||

| North East Buttress | Observatory Gully | |||||

| North East Buttress | 300m | V Diff | Raeburn's Arete | 230m | S | |

| Newbigging's 80 Minute Route | 200m | V Diff | Raeburn's Arete, 1931 Variation | 45m | S | |

| Orient Express | 90m | E2 | Raeburn's Arete, 1949 Variation | 55m | S | |

| Steam Train | 100m | HVS | Green Hollow Route | 215m | V Diff | |

| The Ramp | 150m | V Diff | Bayonet Route | 185m | HS | |

| Newbigging's 80 Route, Far Right Variation | 230m | V Diff | Ruddy Rocks | 180m | V Diff | |

| Rain Trip | 180m | S | ||||

| Green and Napier's Route | 150m | Diff | ||||

| Raeburn's 18 Minute Route | 135m | Mod | ||||

| Slinby's Chimney | 125m | Mod | ||||

| Slinby's Chimney, The Chockstone Variation | 45m | V Diff | ||||

| The Minus Face | ||||||

| Minus Three Buttress | Minus Two Buttress | |||||

| Slab Rib Variation | 150m | Diff | Left-hand Route | 275m | VS | |

| Right Hand Wall Route | 150m | Diff | Left-hand Route, Clough variation | 60m | VS | |

| Wagroochimsla | 150m | VS | Left-hand Route, Left Edge Variation | 80m | VS | |

| Platforms Rib | 130m | V Diff | Central Route | 275m | HVS | |

| Minus Three Gully | 150m | SVS | Right-hand Route | 275m | VS | |

| Subtraction | 275m | E1 | ||||

| Long Division | 240m | E1 | ||||

| Minus One Buttress | The Orion Face | |||||

| North-Eastern Grooves | 295m | VS | Astronomy Direct Finish | 300m | VS | |

| Minus One Direct | 295m | E1 | The Long Climb | 420m | VS | |

| Minus One Direct, Mindless Variation | 20m | E2 | The Long Climb, Variation Alpha | 150m | S | |

| Minus One Direct, Original Finish | 205m | HVS | The Long Climb, Variation Beta | 100m | VS | |

| Minus One Direct, Serendipidy Variation | 266m | HVS | The Long Climb, Variation Zeta | 110m | V Diff | |

| Slav Route | 420m | S | ||||

| Observatory Ridge and West Face | Observatory Buttress | |||||

| East Face | 170m | VS | Left Edge Route | 360m | S | |

| Observatory Ridge | 420m | V Diff | Rubicon Wall | 310m | S | |

| Observatory Ridge, Left Hand Start | 70m | Mod | Observatory Buttress Direct | 340m | V Diff | |

| Observatory Ridge, Direct Variation | 80m | V Diff | Observatory Buttress | 340m | V Diff | |

| Observatory Wall | 90m | V Diff | ||||

| West Face Lower Route | 325m | V Diff | ||||

| Pointless | 330m | SVS | ||||

| Indicator Wall | Gardyloo Buttress | |||||

| Indicator Wall | 110m | V Diff | Left Edge Route | 160m | SVS | |

| Indicator Wall, Direct Variation | 45m | S | Kellet's Route, Augean Alley Finish | 140m | HVS | |

| Psychedelic Wall, Missing Link Variation | 140m | SVS | Kellet's Route, Variation Finish | 50m | S | |

| Gardyloo Gully | 170m | S | Tower Gully | 120m | Easy | |

Ben Nevis' NE face.

(Photo by Ron Walker)

| Tower Ridge | ||||||

| Tower Ridge East Flank | Tower Ridge | |||||

| Clefthanger | 90m | HVS | Tower Ridge | 600m | Diff | |

| East Wall Route | 110m | Diff | Great Tower Variation: Macphee's Route | 45m | V Diff | |

| Rolling Stones | 135m | HVS | Great Tower Variation: Ogilvy's Route | 45m | V Diff | |

| Echo Traverse | 135m | S | Great Tower Variation: Pigott's Route | 45m | V Diff | |

| The Brass Monkey | 130m | HVS | Great Tower Variation: Bell's Route | 45m | V Diff | |

| The Urchin | 60m | E1 | Great Tower Variation: Recess Route | 45m | Diff | |

| Chimney Groove | 110m | Diff | Great Tower Variation: Cracked Slabs Route | 45m | V Diff | |

| Lower East Wall Route | 125m | Diff | Great Tower Variation: Western Traverse | 70m | Diff | |

| Great Tower Variation: Rotten Chimney | 45m | Diff | ||||

| The Douglass Boulder | Secondary Tower Ridge | |||||

| Direct Route | 215m | V Diff | 1934 Route | 185m | Mod | |

| Direct Route III | 200m | V Diff | Beggar's Groove | 175m | V Diff | |

| The Black Douglas | 280m | S | Vagabond's Rib | 200m | S | |

| North -West Face Route | 215m | V Diff | Lady's Day | 120m | V Diff | |

| Militant Chimney | 180m | V Diff | Reprobate's Rib | 155m | VS | |

| Left-Hand Chimney | 215m | Diff | Fat Boy Slim | 120m | V Diff | |

| Right-Hand Chimney | 150m | S | 1931 Route | 125m | Diff | |

| Nutless | 145m | S | 1931 Route, Central Rib Variation | 40m | S | |

| Gutless | 130m | S | Rougue's Rib | 215m | S | |

| Walking Through Fire | 130m | VS | Italian Climb | 180m | S | |

| Cutlass | 135m | VS | The Ruritanian Climb | 225m | S | |

| Jacknife | 90m | S | ||||

| South-West Ridge | 180m | Mod | ||||

| West Gully | 140m | Easy | ||||

| Caragh na Ciste | Pinnacle Buttress of the Tower, | |||||

| Raeburn's Wall and Goodeve's Buttress | ||||||

| Garagh Buttress | 95m | Mod | ||||

| Blue-Nosed Baboon | 135m | V Diff | Pinnacle Buttress of the Tower | 230m | V Diff | |

| Vanishing Glories | 105m | V Diff | Glovers Chimney | 150m | Diff | |

| Cryotherapy | 75m | V Diff | Raeburn's Easy Route | 300m | Easy | |

| Broad Gully | 200m | Easy | The Gutter | 90m | Diff | |

| Coire na Ciste | ||||||

| Number Two Gully Buttress | Comb Gully Buttress and The Comb | |||||

| Number Two Gully Buttress | 120m | V Diff | Comb Gully Buttress | 140m | V Diff | |

| Number Two Gully | 120m | S VS | Lost Face of the Comb | 250m | S | |

| Lost Face of the Comb, Central Wall Variation | 45m | S | ||||

| Lost Face of the Comb, Left-Hand Variation | 60m | S | ||||

| Pigott's Route | 250m | S | ||||

| Number Three Gully Buttress | South Trident Buttress | |||||

| and Creag Coire na Ciste | ||||||

| 1936 Route | 110m | S | ||||

| Number Three Gully Buttress | 150m | Mod | 1934 Route | 100m | Diff | |

| Number Three Gully Buttress, Chimney Variation | 35m | V Diff | 1944 Route | 125m | S | |

| Arthur | 140m | HVS | The Minge | 105m | VS | |

| The Knuckleduster | 120m | HVS | The Rattler | 75m | S | |

| Last Stand | 110m | HVS | The Groove Climb | 75m | V Diff | |

| Sioux Wall | 90m | HVS | Sidewinder | 75m | HVS | |

| The Banshee | 120m | S VS | Strident Edge | 75m | VS | |

| Chinook | 65m | HVS | Devastation | 80m | E1 | |

| Thompson's Route | 110m | Diff | Spartacus | 100m | VS | |

| Central Rib | 120m | Diff | The Slab Climb | 90m | S | |

| Central Rib – Final Tower | 15m | V Diff | Pinnacle Arête | 150m | V Diff | |

| North Gully | 110m | V Diff | Joyful Chimneys | 170m | S | |

| Jubilee Buttress | Central Trident Buttress | |||||

| Nosepicker | 90m | S | Steam | 90m | HVS | |

| Gutbuster | 100m | HVS | Heidbanger | 90m | E1 | |

| Jubilee Climb | 260m | V Diff | Heidbanger,Cranium variation | 25m | E1 | |

| Metamorphosis | 105m | E2 | ||||

| North Trident Buttress | Moonlight Gully Buttress | |||||

| North Trident Buttress | 200m | V Diff | Diagonal Route | 150m | Mod | |

| Geotactic | 45m | VS | Right-Hand Chimney | 150m | V Diff | |

| Softball | 45m | S | Gaslight | 90m | V Diff | |

| Tuff Nut | 45m | HVS |

|

| Carn Dearg | ||||||

| Carn Dearg Buttress | North Wall of Carn Dearg | |||||

| Mourning Slab | 100m | VS | Zagzig | 55m | S | |

| The Blind | 100m | VS | Kellet's North Wall Route | 180m | S | |

| Route I | 215m | S | Kellet's North Wall Route, Caterpillar Crawl Variation | 45m | S | |

| Route I, Direct Start Variation | 70m | S | ||||

| P.M. | 110m | VS | Cousin's Buttress | |||

| Route II Direct | 235m | S | ||||

| Dissection | 165m | HVS | Harrison's Climb Direct | 275m | Diff | |

| The Shadow | 265m | VS | Harrison's Climb Direct, Chimney Start Variation | 20m | V Diff | |

| The Bullroar | 285m | HVS | Harrison's Climb Direct, Dungeon Variant | 90m | V Diff | |

| The Bullroar, Direct Start Variation | 40m | E1 | Cousin's Buttress Direct | 260m | S | |

| The Banshee, Groove Variation | 15m | HVS | ||||

| Adrenalin Rush | 240m | E3 | Raeburn's Buttress | |||

| Cowslip | 190m | E1 | ||||

| Torro | 215m | E2 | Continuation Route | 150m | S | |

| Red Rag | 215m | E2 | Reaburn's Buttress | 150m | V Diff | |

| Centurion | 190m | HVS | Saxifrage | 250m | VS | |

| King Kong | 275m | E2 | The Crack | 250m | HVS | |

| King Kong, Original Start Variation | 70m | E3 | Teufel Grooves | 250m | HVS | |

| The Bat | 270m | E2 | ||||

| The Wicked | 110m | E6 | Castle Corrie | |||

| Sassenach | 270m | E1 | ||||

| Sassenach, Patey Traverse Start Variation | 50m | E1 | Compression Crack | 230m | V Diff | |

| Sassenach, Patey Traverse Variation | 75m | VS | South Castle Gully | 210m | V Diff | |

| The Banana Groove | 105m | E4 | The Castle | 215m | V Diff | |

| Caligula | 110m | E3 | Turret Cracks | 60m | HVS | |

| Cailgula, Caligula Direct Variation | 60m | E3 | The Keep | 80m | S | |

| Agrippa | 85m | E5 | North Castle Gully | 230m | Diff | |

| Titan's Wall | 245m | E3 | ||||

| Boadicea | 100m | E4 | Castle Ridge and North East Face | |||

| Shield Direct | 215m | HVS | ||||

| Evening Wall | 210m | V Diff | Castle Ridge | 275m | Mod | |

| Staircase Climb | 215m | V Diff | Camanachd Heroes | 215m | E1 | |

| Staircase Climb, Straight Chimney Variation | 55m | S | Prodigal Boys | 150m | HVS | |

| Staircase Climb, Raeburn's Variation | 45m | V Diff | Plastic Max | 150m | SVS | |

| Staircase Climb, Deep Chimney Variation | 40m | Diff | Night Tripper | 185n | SVS | |

| The Trial | 45m | E3 | ||||

| Girdle Traverse | ||||||

| The Girdle Traverse | 4000m | S | ||||

| Marathon | 610m | E1 | ||||

| The Orgy | 670m | HVS | ||||

| The High Girdle | 400m | S |

This page's list of climbs in Glen Nevis is only the tip of the iceberg in terms of what is actually there, as the crags at Polldubh (NN 150 687) are host to many quality single and multi-pitch routes. In fact there are enough to justify giving the area a page of its own. Therefore this section will only list the longer routes which take the climber into the higher reaches of the mountain, and terminate within a relatively short distance of Ben Nevis' summit. For a complete list and description of climbs in Glen Nevis see Kevin Howett's Highland Outcrops guidebook.

|

| The Little Brenva Face | North East Buttress | The First Platform | ||||||||

| Final Buttress | 70m | III, 4 | North-East Buttress | 300m | IV, 4 | Raeburn's Arête | 235m | V, 6 | ||

| Bob Run | 120m | II | The Lime Green Gaiter | 70m | V, 6 | Green Hollow Route | 215m | IV, 4 | ||

| Moonwalk | 260m | IV, 3 | Newbigging's 80 Minute Route | 230m | IV, 4 | Bayonet Route | 185m | IV, 4 | ||

| Cresta | 275m | III | Newbigging's 80 Minute Route, Right Hand Variation | 60m | V, 6 | Ruddy Rocks | 180m | IV, 4 | ||

| Cresta Direct | 270m | IV, 4 | Newbigging's Route, Far Right Variation Variation | 230m | IV,4 | Rain Trip | 180m | IV, 4 | ||

| Slalom | 275m | III | Raeburn's 18 Minute Route | 135m | II | |||||

| Super G | 270m | VI, 6 | Slingby's Chimney | 125m | II | |||||

| Frost Bite | 275m | IV, 4 | ||||||||

| Islandhlwana | 280m | V, 5 | ||||||||

| Route Major | 300m | IV, 4 |

| The Minus Face | The Orion Face | The Observatory Ridge | ||||||||

| Right-Hand Wall Route | 140m | IV,5 | Astronomy | 300m | VI,5 | East Face | 166m | IV,5 | ||

| Slab Rib Variation | 150m | IV,5 | Astronomy, Direct Finish | 120m | VI,5 | Silverside | 115m | IV,4 | ||

| Wagroochimsla | 140m | IV,5 | Smith-Holt Route | 420m | V,5 | Observatory Ridge | 420m | IV,4 | ||

| Platform Rib | 150m | IV,4 | The Black Hole | 350m | VI,6 | Observatory Wall | 90m | V,6 | ||

| Minus Three Gully | 160m | IV,5 | Urban Spaceman | 350m | VII,6 | Abacus | 106m | IV,4 | ||

| Left-Hand Route | 270m | VI,6 | Orion direct | 420m | V,5 | Antonine Wall | 150m | V,5 | ||

| Central Route | 270m | VI,7 | Orion Directissima | 375m | VI,5 | West Face Lower Route | 325m | IV,5 | ||

| Right-Hand Route | 270m | VI,6 | Zybernaught | 240m | VI,5 | Vade Mecum | 320m | V,5 | ||

| Minus Two Buttress | 270m | V,5 | Astral Highway | 240m | V,5 | Hadrian's Wall Direct | 320m | V,5 | ||

| Minus Two Gully | 270m | V,5 | Space Invaders | 240m | VI,6 | Sickle | 300m | V,5 | ||

| Minus One Buttress | 290m | VI,6 | Journey into Space | 240m | VII,6 | Galactic Hitchhiker | 300m | VI,5 | ||

| Minus One Gully | 290m | VI,6 | Space Walk | 200m | VII,6 | Pointless | 300m | VII,6 | ||

| Long Climb Finish | 240m | VII,6 | Interstellar Overdrive | 300m | VI,5 | |||||

| Slav Route | 420m | V,5 | Point Five Gully | 325m | V,5 | |||||

| Zero Gully | 300m | V,4 |

| Observatory Buttress | Indicator Wall | Gardyloo Buttress | ||||||||

| Pointblank | 325m | VII,6 | Saturn Rib | 150m | III | Shot in the Light | 100m | IV,5 | ||

| Left Edge Route | 360m | V,5 | Good Friday Climb | 150m | III | Left Edge | 155m | VI,5 | ||

| Matchpoint | 325m | VI,5 | Soft Ice Shuttle | 130m | IV,4 | Kellett's Route | 120m | VI,6 | ||

| Rubicon Wall | 340m | VI,5 | Indicator Wall | 180m | V,4 | Augean Alley | 120m | V,5 | ||

| Direct Route | 340m | V,4 | Flight of the Condor | 200m | VI,5 | Murphy's Route | 130m | V,5 | ||

| Ordinary Route | 340m | V,5 | Riders of the Storm | 165m | VI,5 | Smith's Route | 130m | V,5 | ||

| Never-Never Land | 170m | VI,6 | Albatross | 150m | VI,5 | The Great Glen | 130m | VI,5 | ||

| North-West Face | 100m | IV,4 | Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner | 160m | VII,7 | Right Edge | 130m | III | ||

| Stormy Petrel | 160m | VII,6 | Tower Gully | 120m | I | |||||

| Psychedelic Wall | 180m | VI,5 | ||||||||

| Satanic Verses | 115m | V,5 | ||||||||

| Shot in the Dark | 120m | V,5 | ||||||||

| Caledonia | 100m | V,5 | ||||||||

| Shot in the Foot | 50m | V,4 | ||||||||

| Gardyloo Gully | 170m | II/III | ||||||||

Groups of climbers on Tower Ridge (Photo by Tony Simpkins)

Groups of climbers on Tower Ridge (Photo by Tony Simpkins)| Tower Ridge East Side | Douglas Boulder |

Tower Ridge West Flank |

||||||||

| Tower Scoop | 65m | III | Direct Route | 215m | IV,4 | Fawlty Towers | 155m | II | ||

| Tower Cleft | 75m | III | Down to the Wire | 220m | V,6 | 1934 Route | 185m | II/III | ||

| Clefthanger | 90m | VI,6 | North-West Face Route | 215m | V,5 | Running Hot | 120m | V,5 | ||

| East Wall Route | 110m | II/III | Left Hand Chimney | 215m | IV,4 | Vanishing Gully | 200m | V,5 | ||

| Echo Traverse | 135m | III | Gutless | 180m | IV,5 | Pirate | 200m | IV,4 | ||

| The Edge of Beyond | 200m | V,5 | Western Grooves | 195m | IV,5 | Fish Eye Chimney | 150m | V,5 | ||

| The Great Chimney | 65m | IV,5 | Cutlass | 270m | VI,7 | 1931 Route | 125m | IV,4 | ||

| Chimney Groove | 90m | IV,6 | South-West Ridge | 180m | III | Rogue's Rib | 220m | IV,5 | ||

| Lower East Wall Route | 125m | III | Douglas Gap West Gully | 180m | I | The Italian Climb | 180m | III | ||

| Tower Ridge | 600m- | IV,3 | Italian Climb - Right Hand | 65m | IV,4 | |||||

| 3/4km | Bydand | 150m | V,5 | |||||||

Tower Ridge (Photo by hwackerhage) |

Climbing Tower Gap (Photo by hwackerhage) |

The Chute | 230m | V,4 | ||||||

| Garadh Gully | 95m | I-IV | ||||||||

| Broad Gully | 95m | II | ||||||||

| Pinnacle Buttress of the Tower | 175m | III,4 | ||||||||

| Fatal Error | 230m | IV,4 | ||||||||

| Stringfellow | 240m | VI,6 | ||||||||

| Stringfellow Direct Finish | 240m | V,5 | ||||||||

| Smooth Operator | 210m | VI,7 | ||||||||

| Butterfingers | 220m | V,6 | ||||||||

| Pinnacle Buttress Direct | 200m | V,5 | ||||||||

| Pinnacle Buttress | 150m | IV,4 | ||||||||

| Glover's Chimney | 200m | III,4 | ||||||||

| The Gutter | 275m | IV,4 | ||||||||

| The White Line | 275m | III | ||||||||

| Beam me up Scotty | 155m | III | ||||||||

Top of Tower Ridge (Photo by roadmountain) |

Tower Gap (Photo by Stuart Buchanan) |

Raeburn's Easy Route | 250m | II/III | ||||||

| Raeburn's not so Easy | 285 | III,4 | ||||||||

| Upper Cascade | 125m | V,5/6 | ||||||||

| The Blue Horizon | 100m | IV,4 | ||||||||

| La Panthere Rose | 50m | VI,6 | ||||||||

| The Cascade | 50m | IV,5 | ||||||||

| Rip Off | 120m | IV,4 | ||||||||

| Five Finger Discount | 135m | IV,4 | ||||||||

| Burrito's Groove | 135m | IV,5 | ||||||||